The Silence of Akhenaten: Was the Pharaoh Mute, Blind or Cultic?

The enigma of Pharaoh Akhenaten has captured the imagination of the world ever since Napoleon’s savants brought him to light. Today, every scholar holds steadfast to his or her theory about the monarch’s life, based on both extant and imaginary evidence. The 18th Dynasty king’s motivations for heralding a new religion have been the foremost subject of studies over more than a century. Rarely does one Egyptologist concur with another in reasoning why exactly Amenhotep IV transformed into the hated Akhenaten. Was it merely the strong desire of a megalomaniac to glorify the age-old sun cult; stamp his authority on an apparently ambitious Amun priesthood; introduce a new art and philosophy to the milieu — or was the ruler just not interested in affairs of state, choosing instead to resort to poetry and silence to escape the madding crowd?

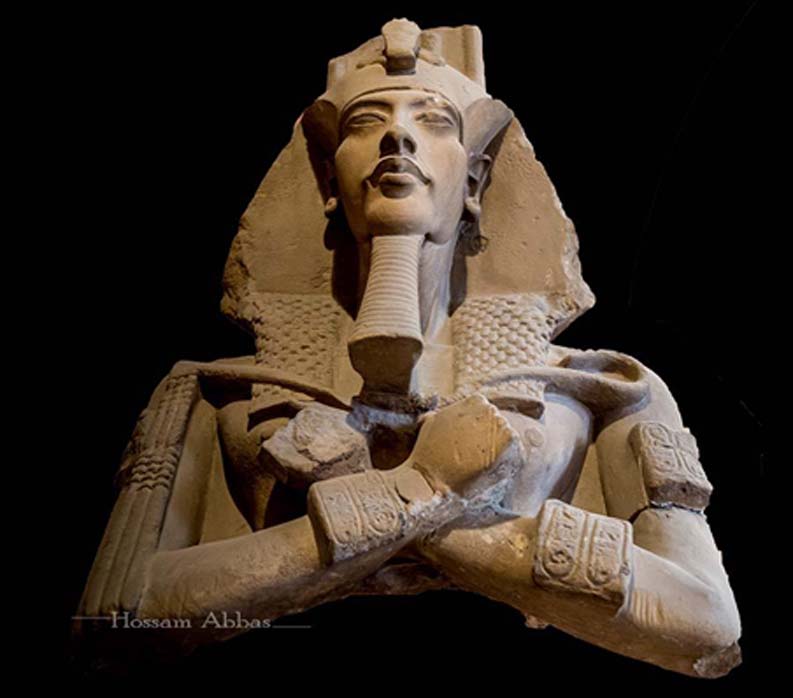

Colossal sandstone statue of Akhenaten discovered at Karnak in 1925 by Maurice Pillet, French architect and director of works for the Egyptian Antiquities Service. Head with nemes and four plumes and upper torso, the distinguishing feature being the squared-off (instead of rounded) wig-like lappets and tail of the nemes headdress. Not only the philosophy of Atenism, but the ritualistic silence the king apparently maintained has for long baffled scholars. Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

It gets rather difficult to address these questions conclusively, because almost all vestiges of the Amarna interlude were destroyed in later years. So much so, that the very idea of the monarch having been history’s first monotheist, is now called into question as the desert sands of Akhetaten yield more fragments of information. However, based on the details we have managed to glean, primarily through sustained archeological efforts, it appears that Akhenaten often chose to maintain a deliberate, studied silence, which meant he did not interact with either his courtiers or subjects often.

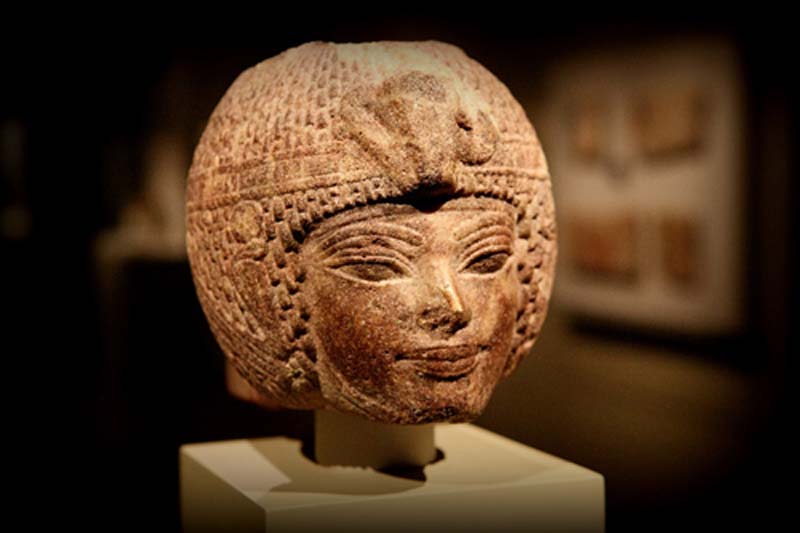

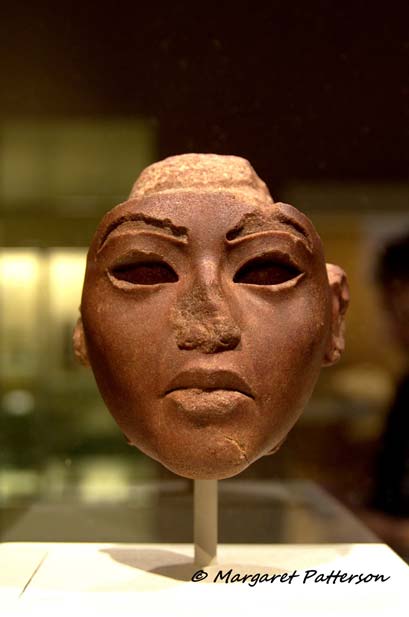

Most probably produced in the last decade of his reign following his first Heb Sed or jubilee, this brown quartzite head shows Amenhotep III wearing the round wig. The king is presented with youthful features. Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland, Ohio. (Photo: Sam Howzit CC BY-SA 2.0)

Revealing Corpus of Clay

Even a glorious sovereign such as Amenhotep III— who was the epitome of juvenescence in his portraits — was not immortal. Shortly after his third jubilee, in Regnal Year 39 the pharaoh who had strode the temporal stage like a colossus, passed on (ca. 1353 BC). While he bequeathed a proud and powerful nation, he also willed a legacy fraught with undercurrents of deleterious political machinations and religious dubiety.

The Amarna corpus that was discovered in 1887 near modern-day Tell el-Amarna provides a fascinating glimpse into diplomacy between ancient Egypt and the rest of the ancient world. The tablets, written in Akkadian, are divided into two groups: the first group comprise correspondence between pharaoh and the rulers of Babylonia, Assyria, Mitanni, Arzawa, Alashiya (Cyprus) and the Hittites.

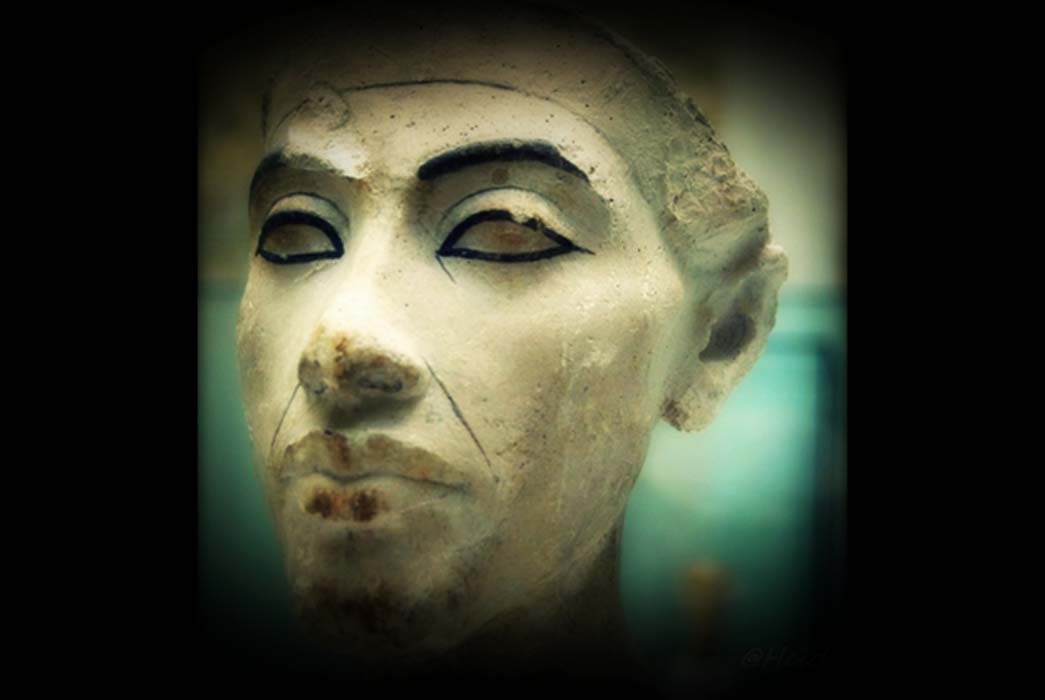

This unfinished quartzite face from a composite statue probably represents Queen Tiye, the brilliant matriarch. As a wife, mother and grandmother, she guided her family admirably—Egypt certainly owed much of its success to Tiye’s astuteness. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.