Asian Storytelling: Rakugo, Pingshu And The Art Of Sitting Seiza

Intertwined with the development of mythologies, storytelling predates writing and the earliest oral storytelling was animated with gestures and expressions thrown in for good measure. Tools to enhance the oral narrative of the prehistorical storyteller could have been rock art, rhythm and dance, all of which contributed to the audience’s understanding and attributing meaning through the remembrance and enactment of the stories. With the advent of writing, prose, poetry, song, choreographed dance, and theatrical performances developed as modes to tell a story, but oral rendering is embedded in the collective memory of humankind.

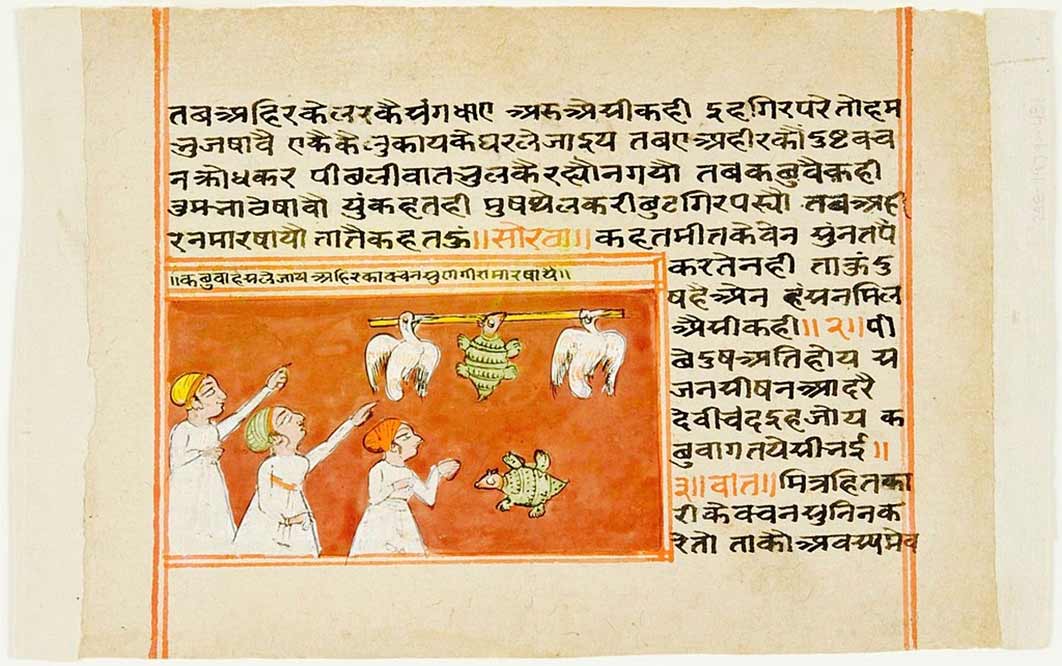

18th century Panchatantra manuscript page, the talkative turtle (Public Domain)

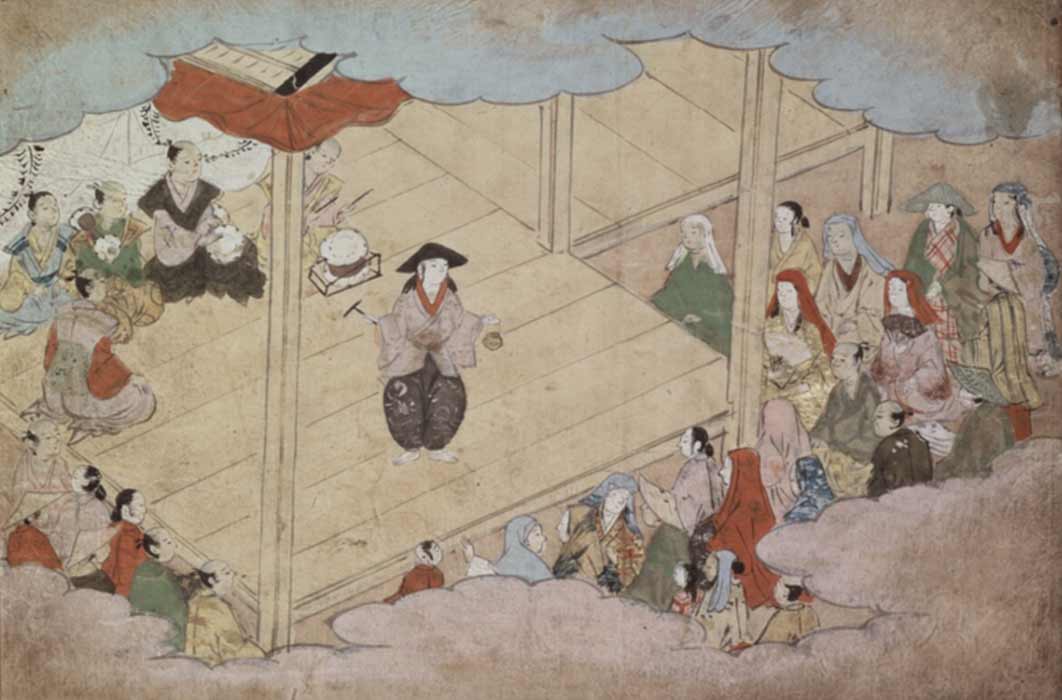

Archaeological evidence confirming the presence of stories has been discovered at the Indus Valley civilization site of Lothal in India. On a large vessel the artist depicted birds with fish in their beaks resting in a tree while a fox-like animal stands below. This scene reminds of a story from the Panchatantra of The Fox and the Crow. The Panchatantra is an ancient Indian collection of animal fables in Sanskrit verse and prose. Although the surviving work is dated to around 200 BC – 300 AD, it was based on older oral tradition. The story of the thirsty crow and deer is depicted on a miniature jar, with the deer unable to drink from the jar's narrow mouth, while the crow succeeded by dropping stones into the jar. The animals' features are distinct and graceful.

The Intimacy Between Storyteller And Audience

Oral storytelling continued to be an irreplaceable tradition as it is a particularly ancient and personal practice shared by the storytellers and their audiences. The storyteller and the audience are usually physically in close proximity, sometimes sitting in a circle. Through the communal experience of storytelling, an intimate bond is formed between the storyteller and the audience, and even between one audience member and another. The flexibility of the art of oral storytelling itself, which allows the tale to be shaped and moulded according to the needs of the audience and the environment of the event, deepens this sense of intimacy and connection. The listeners would also have appreciated being present while a creative process unfolded in their presence in real time, as well as the sense of empowerment that comes from being a part of that creative process.

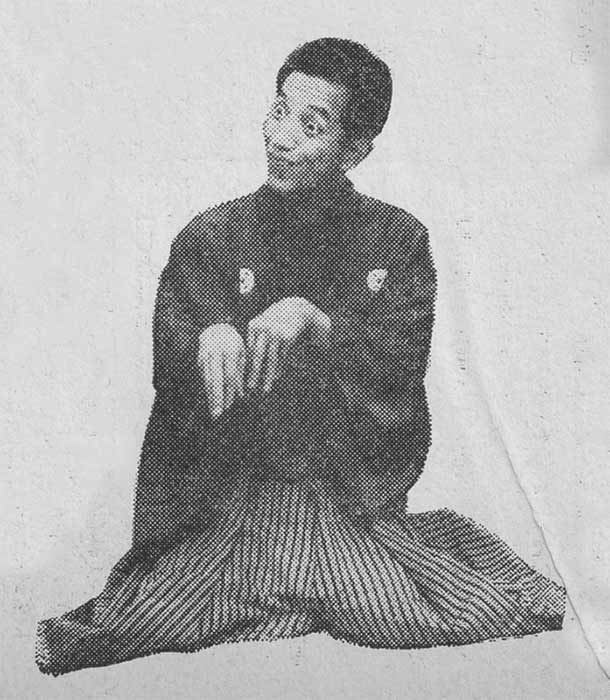

Sanshotei Shoza, a Rakugoka immersing himself in a story (1966) (Public Domain)

The storyteller, in turn, would have had to be adaptable. They would have had to immerse their own personality into the story or may have chosen to include additional characters to make their stories more interesting or relatable. To achieve this, they may have had to change their accent from one character to another or moved in a specific way to enact a scene. As a result, depending on the creative strategies or devices that they chose to employ, there could have been numerous variations of a single story coming from one person.

Expectations Of Epic Storytellers

One example illustrating the ancient world's value of storytelling is the ninth-century fictional storyteller Scheherazade’s One Thousand and One Nights where she saves herself from execution by telling stories to the sultan every night. In India, hundreds of years before Scheherazade, Vyasa reflects on the sacredness of the power of storytelling at the beginning of the Indian epic Mahabharata. "If you listen carefully," Vyasa says, "you will end up being someone else."