Third-Century Roman Empire: Revival From Chaos 270 – 285 AD

During the period designated by modern historians as the era of Roman military anarchy which lasted from 235 to 285 AD, 20 generals unconventionally elected as emperors fought and succeeded each other in rapid succession. To add to the confusion, an equivalent number of pretenders also took arms in attempting to grasp the purple cloak. By 270, the Roman world which had been confronted with the tribulations of these troubled times for more than three and a half decades, was facing obliteration. Besides the Empire having lost about half of its territory, Barbarian incursions were constant, and the provinces were devastated. The weakened and divided military, which had become very influential on the political scene, was still making and defeating emperors at its whim. The army leaders seemed to be more concerned with their own well-being than that of the Empire they were supposed to protect.

Map of the Roman Empire around the year of the consulship of Aurelianus and Bassus (271 AD), with the breakaway Gallic Empire in the West and the Palmyrene Empire in the East. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

During this turbulent period, the balance of the imperial finances became elusive. A gradual devaluation affected the Roman currency, and inflation was on the rise. Many emperors had the goodwill and capabilities to reign, but the missing ingredients were stability and time. Not surprisingly, the general context of a permanent crisis and the limited availability of resources made the task of the holder of the purple cloak extremely laborious and perilous. The condition of the peasants deteriorated considerably during that time as they remained the victims of frequent passages of armies and of overwhelming taxes. The Senate, whose active role on the political scene had been greatly diminished since the time of the Antonine Emperors, was now only a representative and barely consultative body.

Aurelian (270-275)

The son of a peasant from Illyria, Aurelian was a poorly educated, severe and rude career soldier, but he was energetic, strong, honest, and endowed with natural intelligence. In 242, under Emperor Gordian III, he distinguished himself as a tribune at the head of an auxiliary cohort during the campaign against the Sarmatians. In 253, with Emperor Gallienus, he stood out during the campaigns against the Germanic invaders. Aurelian, who was to become one of the great emperors of the century, was undoubtedly among the conspirators responsible for the assassination of Gallienus in Milan in 268, which led to the elevation of Emperor Claudius Gothicus. The most active of Gothicus’ lieutenants, he obtained command of the mobile cavalry and again distinguished himself alongside the Emperor during the campaign against the Alemanni in northern Italy.

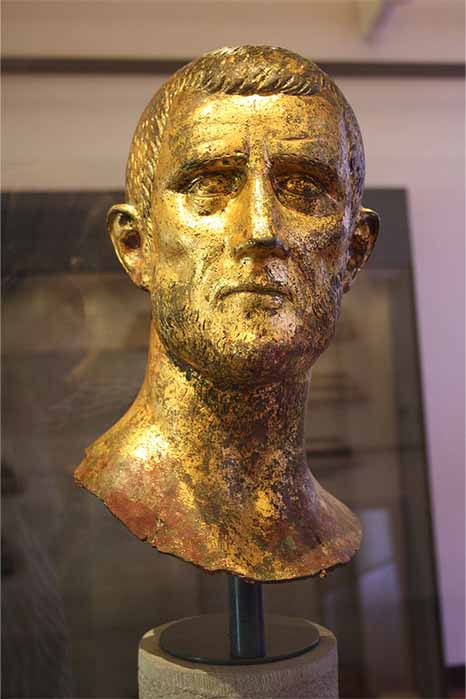

Bronze bust of Aurelian. Santa Giulia Museum, in Brescia, Italy (Giovanni Dall'Orto/ CC0)

Aurelian’s reign halted the decline of the Empire that had been triggered by the death of Emperor Severus Alexander in 235 and even brought about a progressive restoration of the Roman order in Europe. His five-year reign was divided into three phases. During the first, Aurelian pursued what Gothicus had undertaken and repulsed the Germanic invaders on the Upper Danube. Once the region became peaceful again, the second phase of his reign began. It was to restore the unity of the Empire. The relative calm at the borders and the absence of usurpers offered Aurelian the necessary leeway to reign properly. That was not the case during the reigns of his immediate predecessors. In 272, Zenobia, Queen of the independent Kingdom of Palmyra, declared the total autonomy of her kingdom by removing the effigy of the Emperor on her coins. Unable to accept this extreme affront, Aurelian decided to retake the dissident territories. Following two campaigns in the East, Aurelian succeeded in retaking the entire East, and the formerly short-lived metropolis of Palmyra was transformed into a military outpost.

- Military Anarchy Period Of The Roman Empire: Descent Into Hades 235-250 AD

- Goths On The Move: The Third Century Barbaricum Invasion of the Roman Empire

- The Men Who Ruled The World From Rome

- The Roman Empire’s Pragmatic Puzzle Of Provinces

Immediately after, the Emperor devoted himself to retaking Gaul, Britannia and Hispania also detached from the yoke of Rome. Here again, the time to act was right. Overwhelmed by Germanic invasions on its territory, Tetricus, the ‘Emperor’ of the self-proclaimed Gallic Empire, already had his hands full when Aurelian’s army faced him for battle. Whether this was the result of a secret agreement between Tetricus and Aurelian or necessary after his defeat in battle, Tetricus surrendered. Aurelian spared Tetricus and even made him a senator and governor of Lucania in southern Italy. He died of natural causes a few years later. In 273, the unity of the Roman Empire was restored, and Aurelian began the last phase of his reign, that of reorganizing the Empire.