Tutankhamun and the Age of Appropriation: Missing Skullcap of the Last Sun King–Part II

The oft-repeated phrase “the Amarna era is shrouded in mystery” could be a thing of the past if only closer scrutiny of key artifacts from Tutankhamun’s tomb are permitted by the authorities concerned. Courtesy reuse and usurpation, the cleverly disguised inscriptions can yield a wealth of information on the political and religious upheaval of that period, and enable us to peer through the mists of time to gain accurate insights into one of Egypt’s most puzzling epochs. Among the plethora of KV62 mysteries, a modern one exists in the form of Tutankhamun’s missing skullcap.

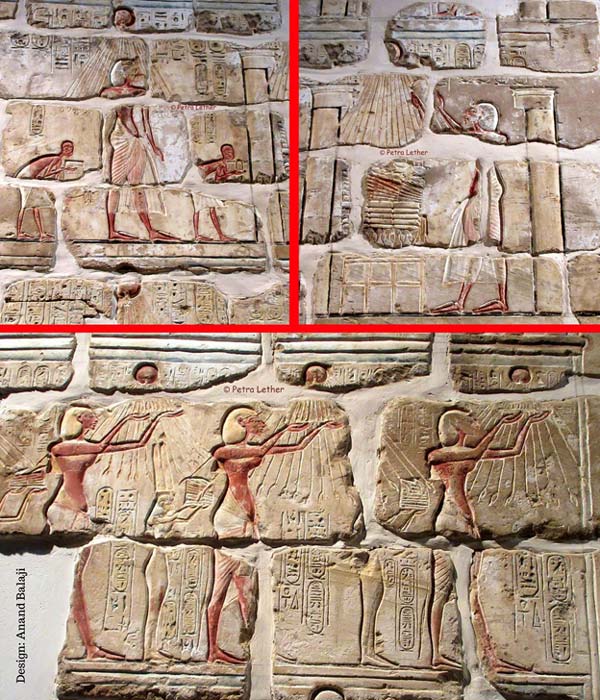

Brilliantly painted Talatat blocks reveal a glimpse of the splendor of Amarna art. (Top) In his role as High Priest, Akhenaten makes offerings of food and worships the Aten. In the scene below, the pharaoh revels in the rays of the sun as he venerates the solar disc. Luxor Museum. (Photos: Petra Lether)

TAINTED GOLD AND FORGOTTEN KINGS

Dr Nicholas Reeves proposes that as co-regent, Nefertiti adopted a kingly name: Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten. And when Akhenaten died in Regnal Year 17 she succeeded as independent pharaoh, her name now changed to Ankhkheperure Neferneferuaten Smenkhkare-Djeser-Kheperu.

A close-up of a limestone relief shows an extraordinary representation of Queen Nefertiti smiting a female captive on a royal barge; a depiction reserved only for male pharaohs. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (Captmondo/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Revealing details from his studies, Dr Aidan Dodson writes, “In 1998, French Egyptologist Marc Gabolde pointed out that a number of cartouches of Neferneferuaten that had been read as using the epithet “Mery-Akhenaten” actually bore the epithet “akhet-en-hi-es” —“effective for her husband.” The correctness of these readings by Gabolde was confirmed beyond any doubt by exhaustive reassessments of the palimpsest (or altered) inscriptions inside the canopic coffinettes ultimately used for Tutankhamen, which had long been known to have been usurped from Neferneferuaten: wherever the epithet could be detected, it was indeed “akhet-en-hi-es.””

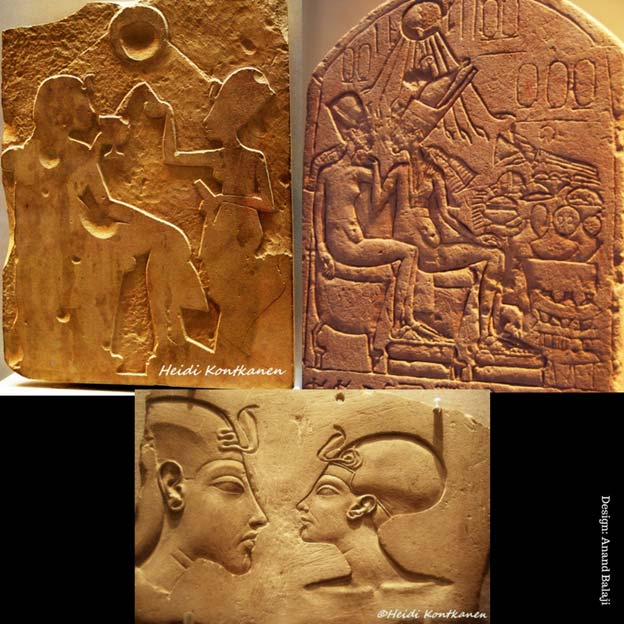

Such scenes are extremely rare in Egyptian art; in fact, these constitute the only examples of a king and queen sharing intimate moments. But, when Akhenaten came to the throne he dictated the course of art—the results are staggering as they are impressive. (Neues Museum, Berlin and Brooklyn Museum, New York.)