Twelfth Night Revelries: Myrrh, Mirth And Making Merry, 5 – 6 January

In the Christian church, January 6 is commemorated as the feast of Epiphany, the day on which the three wise men, or three kings, arrived at the stable in Bethlehem to visit the newborn baby Jesus. In 1756, during the reign of King George II, The Gentleman’s Magazine reported that: ‘His Majesty, attended by the principal officers at Court ... went to the Chapel Royal at St James’ and offered gold, myrrh and frankincense.’ By the 19th century, however, these religious celebrations on January 6 had become almost forgotten, outside of the church itself. By the time of Charles Dickens’ birth (1812), the celebration of Twelfth Night in Britain was much more closely associated with parties and drinking, than with the original religious holiday. There is often debate about when Twelfth Night should fall, as the 12th evening after Christmas Day is actually January 5.

17th-Century Twelfth Night

For many centuries, it was traditional for leaders of the Twelfth Night revels to be chosen and named as the ‘King’ and ‘Queen; as such, it was in their power to dictate what the rest of the gathered party should do. Traditionally, these monarchs were chosen by chance; everyone present at a party would be given a slice of what was known as Twelfth Cake, inside which had been baked a dried bean and a dried pea. Whoever discovered these in their slice of cake became a monarch: getting the dried bean meant being the King and the dried pea meant being the Queen. This quotation from Robert Herricke’s poem Twelfe Night, or King and Queene (c.1630s) shows that this was common in the 17th century: “Now, now the mirth comes with the cake full of plums, Where Beane’s the King of the sport here; Besides we must know, the Pea also must revell, as Queene, in the Court here.”

Scene from Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night by Francis Wheatley (1771–72) (Public Domain)

The diaries of the 17th-century courtier Samuel Pepys, show that he celebrated it on January 6, except for in those years when it fell on a Sunday, when celebrations were deferred until the Monday. On January 6, 1663, he recorded: “6th (Twelfth Day). Up and Mr. Creed brought a pot of chocolate ready made for our morning draft, and then he and I to the Duke’s, but I was not very willing to be seen at this end of the town, and so returned to our lodgings, and took my wife by coach to my brother’s, where I set her down, and Creed and I to St. Paul’s Church-yard, to my bookseller’s, and looked over several books with good discourse, and then into St. Paul’s Church ... So to my brother’s, where Creed and I and my wife dined with Tom, and after dinner to the Duke’s house, and there saw “Twelfth Night” acted well, though it be but a silly play, and not related at all to the name or day.... This night making an end wholly of Christmas, with a mind fully satisfied with the great pleasures we have had by being abroad from home, and I do find my mind so apt to run to its old want of pleasures, that it is high time to betake myself to my late vows, which I will to-morrow, God willing, perfect and bind myself to, that so I may, for a great while, do my duty, as I have well begun, and increase my good name and esteem in the world, and get money, which sweetens all things, and whereof I have much need. So home to supper and to bed, blessing God for his mercy to bring me home, after much pleasure, to my house and business with health and resolution to fall hard to work again.”

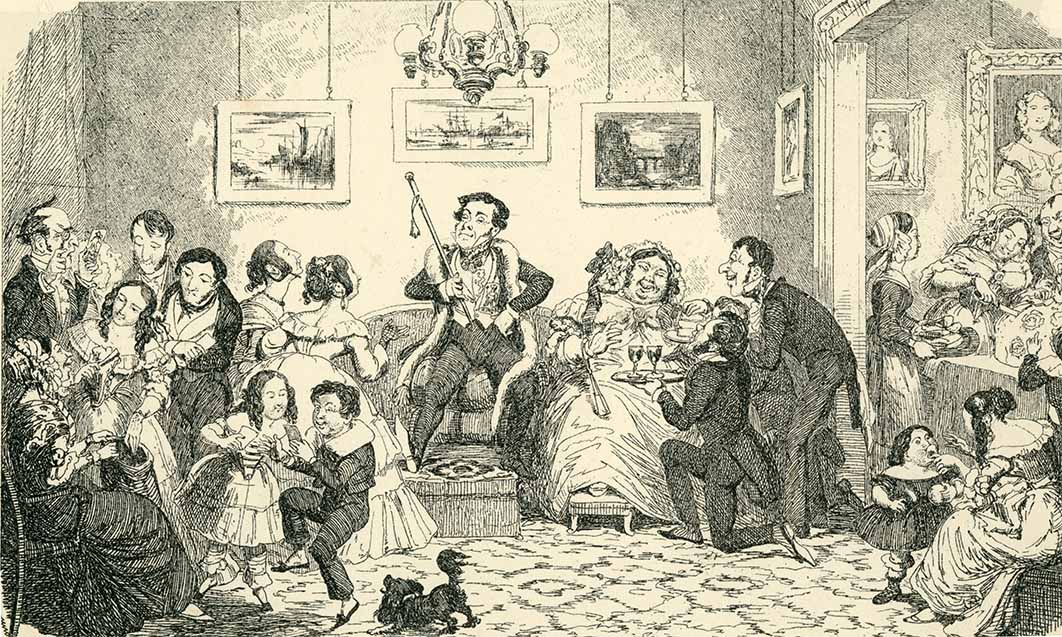

Twelfth Night Revelry (Archivist/ Adobe Stock)

In 1665, Pepys wrote rather irritably in his diary that his wife and her friends had continued the Twelfth Night party long after he had decided to go to bed and that his wife did not go ‘to bed at all’. In 1669, Pepys wrote with relish about their Twelfth Cake and his family’s Twelfth Night revels: “… very merry we were at dinner, and so all the afternoon, talking, and looking up and down my house; and in the evening I did bring out my cake – a noble cake, and there cut it into pieces, with wine and good drink: and after a new fashion, to prevent spoiling the cake, did put so many titles into a hat, and so drew cuts; and I was the Queene; and Turner, King – Creed, Sir Martin Marr-all; and Betty, Mirs Millicent: and so we were mighty merry till it was night; and then, being moonshone and fine frost, they went home, I lending some of them my coach to help carry them, and so my wife and I spent the rest of the evening in talk and reading, and so with great pleasure to bed.”

- An Ancient Treat: The Rich History of Fruitcake

- Traditions of Twelfth Night: Dismantling the Christmas Tree

- Is There a Right Time to Take Down Your Christmas Decorations?

A 17th-century recipe book, A True Gentlewoman’s Delight (1653) by Elizabeth Grey, the Countess of Kent, includes a recipe for a ‘spice cake’, the type of cake used to create a Twelfth Cake: ‘Take one bushel of Flower, six pound of Butter, eight pound of Currans, two pints of Cream, a pottle of Milk, half a pint of good Sack, two pound of Sugar, two ounces of Mace, one ounce of Nutmegs, one ounce of Ginger, twelve yolkes, two whites, take the Milk and Cream, and stirre it all the time that it boyles, put your Butter into a bason, and put your hot seething Milk to it, and melt all the Butter in it, and when it is bloud-warm temper the Cake, put not your Currans in till you have made the paste, you must have some Ale yest and forget not Salt.’