Searching For True Monarchy In Greek Literature

Since the beginning of time monarchs and monarchy have attracted a great deal of attention in the media. Countless works of history have focused on the deeds and misdeeds of political leaders, and many writers of fiction have likewise devoted much of their energy to such characters. However, insight into the true nature of the power structure in any given society has been rare. There have only ever been essentially two types of government: monarchy and oligarchy (or aristocracy). True monarchy is populist and anti-aristocratic. This means that many crowned heads are not true monarchs at all, while many other supposedly non-monarchical political leaders really are monarchs in the true sense.

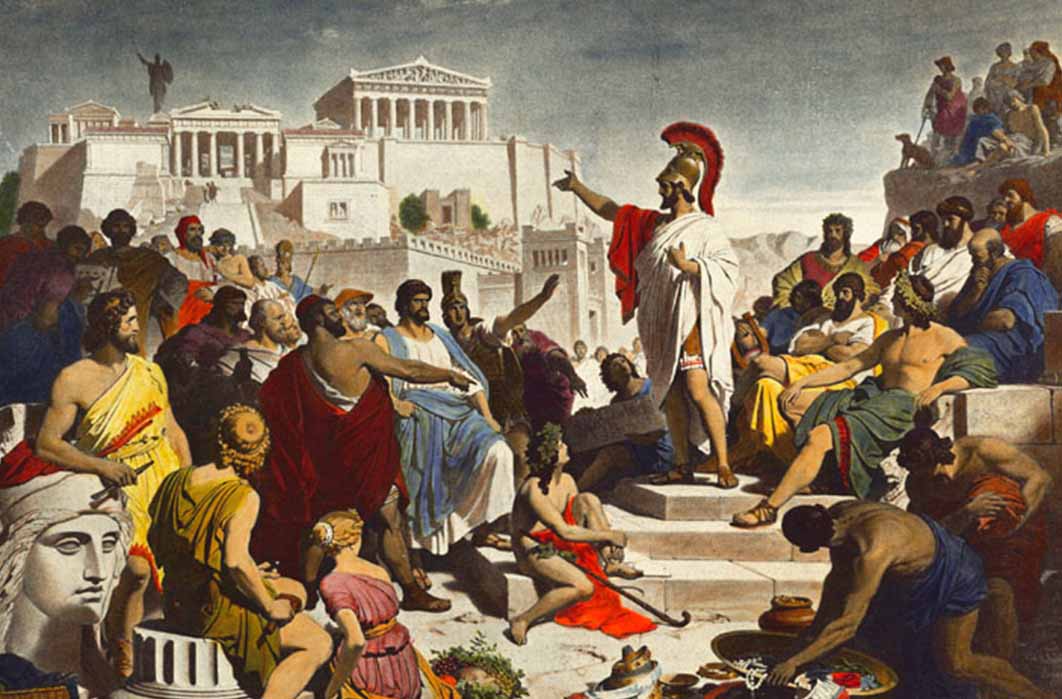

Homeric Kings: Menelaus, Paris (prince), Diomedes, Odysseus, Nestor, Achilles, Agamemnon, by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein. (Ostholstein-Museum Eutin/ CC BY-SA 4.0)

Homeric Kings

In Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey the focus is on kings and aristocrats, with hardly even a look-in for anyone of lower birth. The modern sceptics, like Sir Moses Finley (1964), who pooh-poohed Homer as providing a reliable reflection of Mycenaean society, have been decisively trounced. The Homeric epics do not claim historical accuracy, but their reflection of the power structure of Mycenaean Greece is corroborated by both archaeology and linguistics. Homer’s picture of Agamemnon, King of Mycenae, as heading up a loose alliance made up of the rulers of Sparta, Pylos, Ithaca and other regional states conforms broadly to the excavated archaeological pattern of lavish palace-centred states. The decipherment of Linear B has likewise revealed that each of these states was ruled by a wanax (or anax in Homer and Classical Greek), meaning a king with religious as well as political, military and judicial power. Basileus, the standard word for king in classical and modern Greek, is the title for a fairly lowly local official in Linear B, and in Homer it can refer either to the ruler of one of the regional states or to members of the aristocracy, like Penelope’s suitors in Ithaca. Homer’s anax is much more of a true monarch than the wanax of Linear B, who, despite his apparently all-encompassing power, is the head of a multi-layer bureaucratic hierarchy.

The Greek Tyrants

True monarchy is essentially anti-aristocratic and populist. Ancient Greece provides a good example of this in the shape of the so-called tyrants, whose heyday was from 650 to 550 BC, though tyrants pop up in later periods of Greek history as well. Tyrannies arose on the overthrow of aristocratic (or oligarchic) governments. Today the word “tyrant” has pejorative connotations, but these bad associations date only from the fifth century BC. Before that the word had simply been a neutral synonym for “king,” and there is strong evidence that in their own day the tyrants were genuinely popular leaders of anti-aristocratic movements.

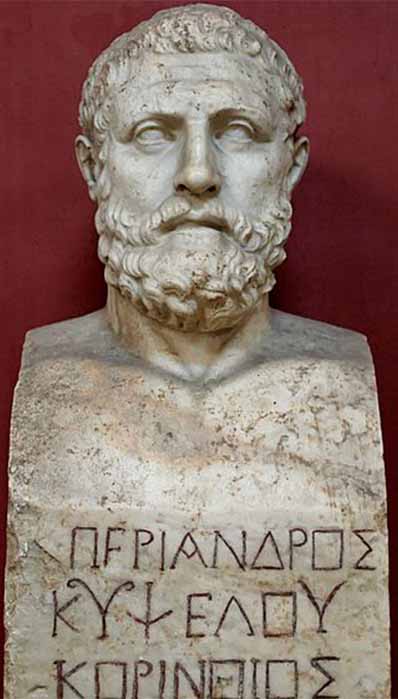

Bust of Periander bearing the inscription “Periander, son of Cypselus, Corinthian”. Marble, Roman copy after a Greek original from the fourth century (Public Domain)

But how are they represented in literature? Aristotle in Politics put the tyrants’ typical power-base in a nutshell: “The majority of tyrants have generally developed out of demagogues who have gained the confidence of the people through their attacks upon the nobles.” The tyrants’ approach to the rich and noble is graphically illustrated by an anecdote related by Herodotus concerning Periander, tyrant of Corinth (r. c. 627–585 BC), and his fellow tyrant, Thrasybulus of Miletus. Aristotle tells the same story, with roles reversed. The story as told by Herodotus is that Periander sent a herald to Thrasybulus to ask his advice on the conduct of government. His advice was lost on the messenger, because it was mimed rather than spoken and amounted in fact to a graphic demonstration of the policy he was recommending: Thrasybulus led the man who had come from Periander outside the city. Entering a sown field, he walked through the corn questioning and interrogating the herald about his voyage from Corinth, and all the time he was lopping off any ears of corn that he saw projecting above the others, and he cast them aside as he cut them down, until he had destroyed the best and richest portion of the crop by this means. Though this charade may have been wasted on the servant, it was certainly not lost on his master. This graphic demonstration epitomizes in itself the role of the tyrant as the enemy of the rich and noble and as a leveler. Is this charming anecdote historical? Most probably. Not only does it ring true, but in view of the reversal of roles, Aristotle’s version would appear to derive from a separate source from Herodotus’. But it really makes no difference whether it is true or not. As they say in Italian: se non è vero, è ben trovato. (“If it’s not true, it’s plausible.”)

Tarquinius Superbus, depicting the king sweeping the tallest heads from a patch of poppies, by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1867) (Public Domain)