Unraveling Tutankhamun’s Final Secret: Cloak of Mysteries Reside in a Sepulchral Masterpiece–Part I

Are we poised to discover an Amarna royal in a hitherto unimagined location that will rewrite history — or will this be the final nail in the coffin for the ‘double burial’ theory? It is quite possible that the sarcophagus of the boy-king holds unrecognized secrets. Recent scans by Italian experts in the tomb of Tutankhamun have apparently gathered pace, and the Egyptological world eagerly awaits the results of their research.

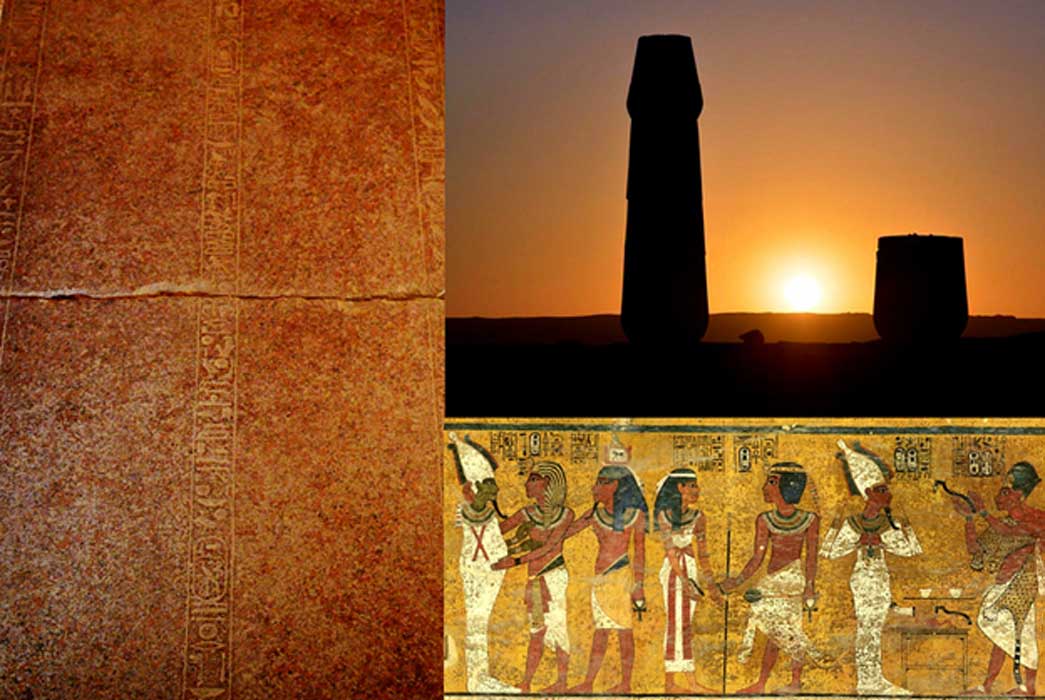

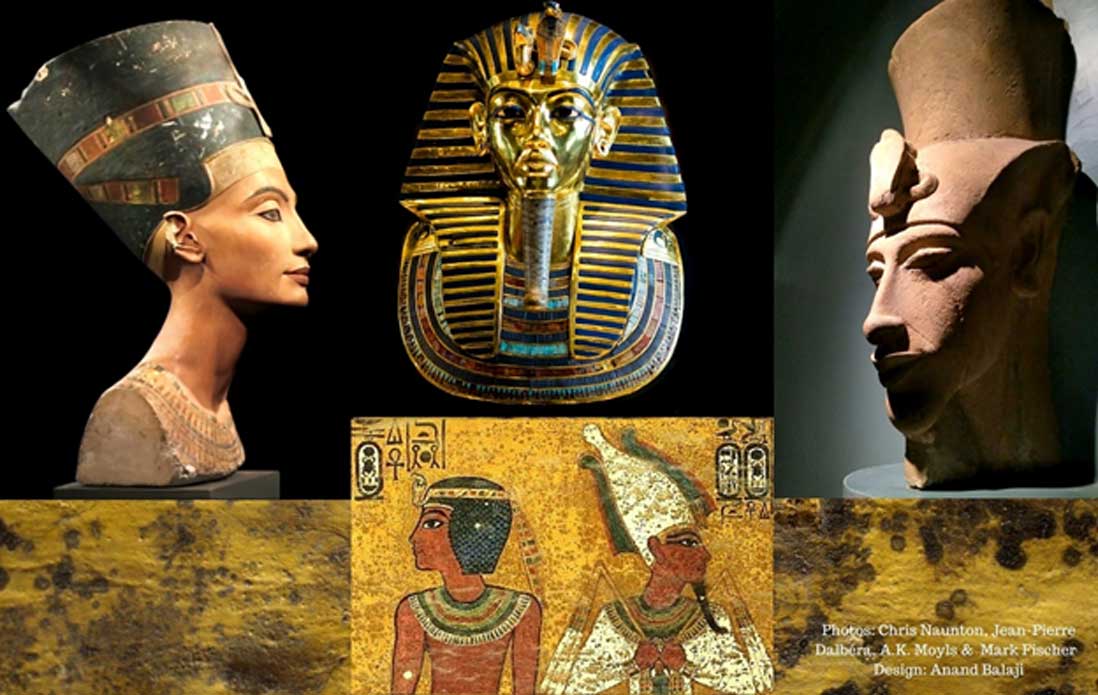

(From left) The painted bust of Queen Nefertiti (Berlin Museum/CC BY 2.0); Tutankhamun’s golden mask (Cairo Museum/CC BY-SA 2.0); remnants of a colossal sculpture of Akhenaten discovered at Karnak (Luxor Museum); funerary scenes on the north wall of KV62 and (Background) fungoid spots on a wall in the tomb.

SEEKING SCATTERED ROYALTY

Nearly a century after the discovery of Tutankhamun’s “House of Eternity” in the Valley of the Kings in 1922 — which, by Howard Carter’s own admission was a ‘demi-royal’ tomb — many mysteries remain. A plethora of enigmas can be cited in its structure, grave goods, and other forms of evidence that point to a hurried burial. The Welsh-American author Jon Manchip White writes in his foreword to the 1977 edition of Carter’s ‘The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun’, “The pharaoh who in life was one of the least esteemed of Egypt’s Pharaohs has become in death the most renowned.” This is an accurate assessment.

Post the Amarna epoch, in the latter half of the Eighteenth Dynasty, a new ruler, nine-year-old Nebkheperure Tutankhaten Hekaiunushema restored the Amun-Re cult by Regnal Year 3 and changed his nomen to Tutankhamun. Decisions taken on behalf of the child-king by two future pharaohs - éminence grise Aye and generalissimo Horemheb - who were old family retainers, meant that the capital city his putative father Pharaoh Akhenaten had established was no longer bound to be the seat of power. Thus, Akhetaten was gradually stripped of its glory and the old ways held sway once more.

This head of indurated limestone is a fragment from a statue group that represented the god Amun seated on a throne and Tutankhamun standing or kneeling in front of him. All that remains of Amun is his right hand, which touches the back of the king’s crown in a gesture that signifies Tutankhamun’s investiture as king. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The court moved back to Thebes and the royal dead too were re-interred in Ta-sekhet-ma’at (the Great Field); known today as the Valley of the Kings. It is highly probable that the exhumed bodies from the Royal Wadi in Akhetaten included: Akhenaten, Queen Tiye, Nefertiti, Meritaten, Kiya, Smenkhkare, Meketaten, Neferneferure and Setepenre. The mortal remains of Tiye – and possibly Akhenaten – seem to have found their way into the mystifying Tomb 55 (KV55) in the central part of the Valley.

Various views of the splendid KV55 coffin with the cartouche naming the owner excised and the sheet gold face torn away. Its rishi-style is mirrored by the second anthropoid coffin of Tutankhamun. Egyptian Museum, Cairo.