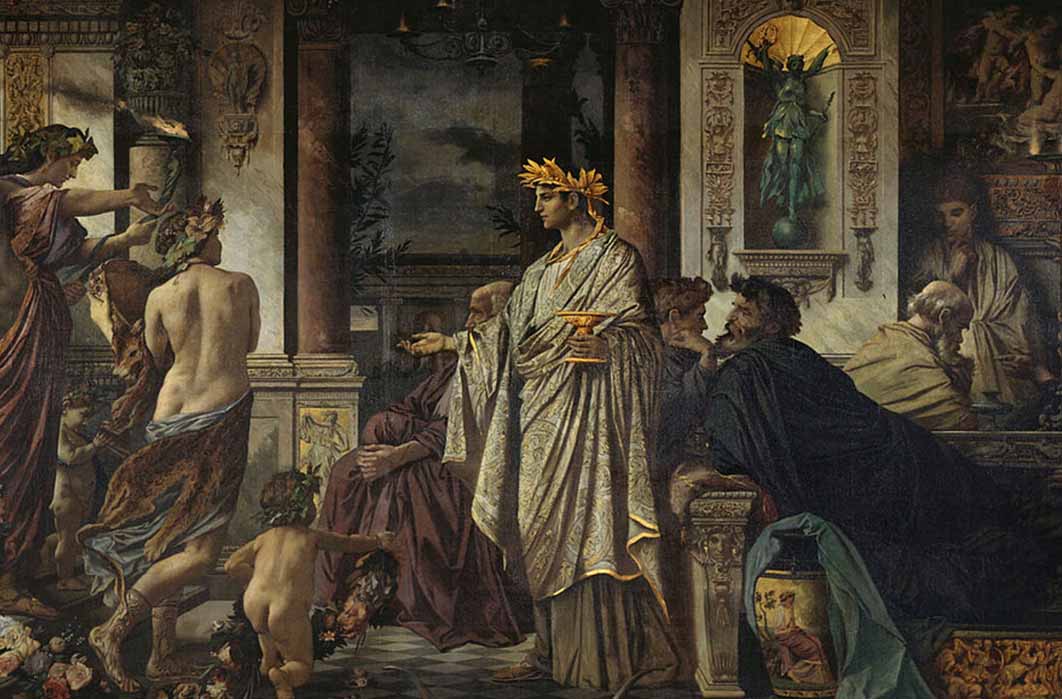

Utopia, Euphoria: Greek Philosophers Searching For The Good Life

To the ancient Greeks, philosophy – literally the love of wisdom - as a therapy or treatment of bodily ailments implied a holistic, psychosomatic understanding of the human mind, body and soul. Conversely, some Greek doctors whose writings have come down under the collective label of ‘Hippocratics’ -in honor of a real Hippocrates, from the island of Cos, an older contemporary of Athenian Plato - philosophized for example, about whether or not disease in general or any one particular disease (such as epilepsy) could be considered to be of divine, super-human origin and causation. Could the ancient Greek philosophers assist modern man in attaining utopia, a good life within a good community, and did the irrational gods have any influence?

Bust of Plato (ca. 370 BC) Academia in Athens (Public Domain)

Plato’s Theaetetus

Plato, who possibly coined the original term ‘philosophia’, was big on medical metaphors – sometimes regarding philosophical nostrums as specifics for the betterment or cure of a sick body politic, at other times for a morally unhealthy individual soul. Much of Plato’s philosophy was to do with individual ethics, right and wrong, justice and injustice, where goodness, for him, required an ultra-high level of intellectual capacity. His most famous pupil Aristotle cast his intellectual net far wider, though he too wrote memorably on ethics, and especially on the ethics of friendship, but for him the social-political context of behavior mattered as much as did personal probity.

Plato presented his philosophy through the medium of invented dialogues, tried out first on his pupils at his Athens Academy of higher learning (founded in the 380s), later published on papyrus as finished works, many of which are also considered masterpieces of prose literature. They exemplify the so-called ‘Socratic’ Question-and-Answer method of enquiry, so named because Plato’s mentor Socrates (who never wrote a word) is featured in almost all of his dialogues as the principal interlocutor. It must be emphasized that these dialogues are not transcripts, but Platonic creations or fictions. The ‘Socrates’ character is very much Plato’s version of him. Plato lived to a very great age, and the dialogues were published over some three decades; the Theaetetus, named for one of Socrates’ two principal discussants, is thought to fall towards the end of that period.

Like most of the earliest, this dialogue focuses on a single definitional question, a matter of epistemology: What is knowledge? Theaetetus has three attempts at trying to define it, and none of them satisfies ‘Socrates’. The aporetic (no decisive answer reached) discussion then turns to another, related question: What counts as ‘to give an account’, to construct a logos (literally ‘word’, by extension speech, reasoning, account) of any complex concept? Again all three explanations or justifications offered are deemed to fail, leading once again to aporia (literally no way forward or through, though discovering that to be the case a reading of it can of course be a positive gain). Plato’s Theaetetus was in real life a brilliant mathematician.

Ruins of the ancient Temple of Apollo at Delphi, overlooking the valley of Phocis ( Skyring/ CC BY-SA 4.0)

Know Thyself

‘Know thyself’ is one of the three maxims incised on the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, along with ‘Nothing to excess’ and ‘Never stand surety for a loan’. Apollo was a god of healing as well as poetry and the arts, long before philosophy as such was invented as a separate intellectual discipline. So, what he – or rather his priests - would have understood by ‘know yourself’ is probably quite different from Socrates’ take.

- Did He Create a Blissful Utopia or a Tyrannical Communist Nightmare? Plato’s Ancient Class System and Social Engineering Revealed

- Aristotle is Dead, but his Ideas are Alive: On Private Property and Moneymaking

- Elusive Epicurus, Hellenistic Greek Philosopher In Search Of Happiness

Not only is ‘Know Thyself’ not a Socrates original, but actually, nothing that has been preserved as a saying of his is certainly authentic, since he himself never wrote a word of his philosophy. What survived are sayings or teachings attributed to him – mainly by two of his disciples, Plato and Xenophon (circa 428 -354 BC); a multi-author on history, warcraft, horsemanship, public economics, biography, as well as philosophy.