Ancient Greek Theophanies, Ghosts And Hallucinations

Gods and goddesses revealed themselves rather remarkably often to the privileged and chosen ancient Greeks, even if it was in disguise to hide their blinding brilliance. Like English, Greek did not make a linguistic distinction between the optical faculty and the appearance of a divine being or ghost, as indicated by the range of meanings conveyed by the word ‘vision’. Similarly, doxa, can either mean, ‘that which is seen’ or ‘an apparition’. This overlap or ambivalence may reflect an unconscious awareness that seeing the phenomenal world and seeing something in what is called the mind’s eye, are not distinct but closely related experiences. Humans are capable of visualizing events both in the past and in the imagination – when writing the word ‘elephant’ the image of an elephant magically appears before the author conjured up by the imagination and by memory of what an elephant looks like. Humans are also capable of visualising events as they are taking place in front of their eyes. Moreover, an image that was implanted in the brain in childhood can remain alive and be recalled with all the clarity and distinctiveness of an image that was implanted in the brain only yesterday.

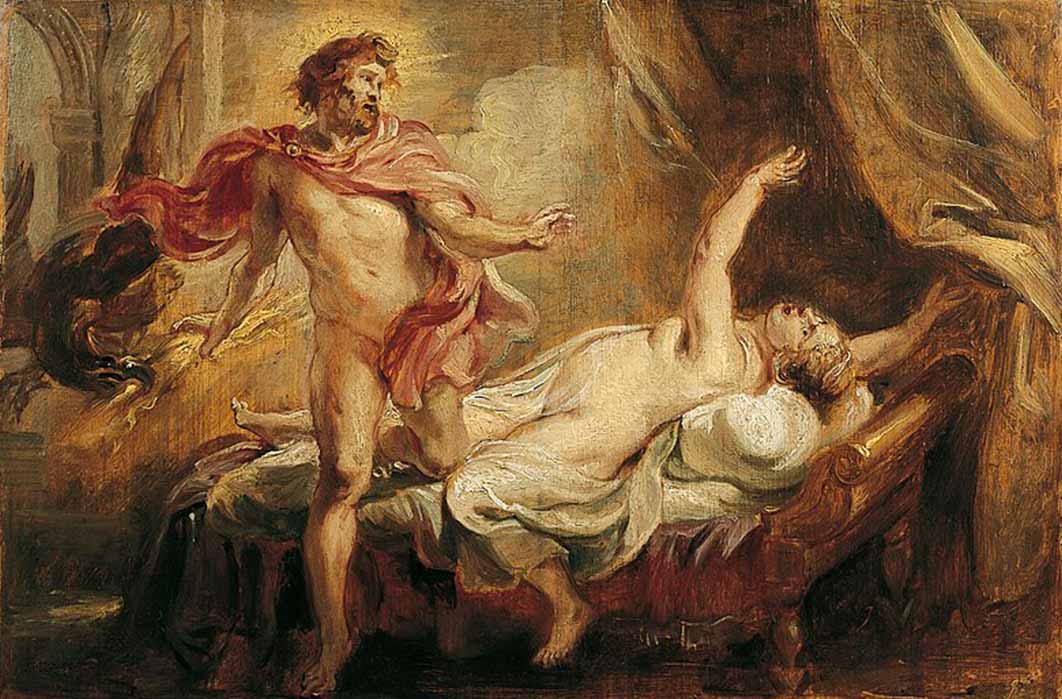

Theophanies

At the beginning of Homer’s Iliad, Athena manifested herself to Achilles in the war council that Agamemnon had summoned, just when Achilles, mortally insulted, was about to draw his sword and kill his commander-in-chief. At that precise moment, however, Athena swooped down and snatched him by the hair, whereupon he turned around “and she appeared to him alone.” Mortal and immortal then proceeded to hold a private conversation that goes on for 20 lines. No-one else heard the conversation, nor did anyone realize that Achilles was otherwise engaged. It is as if time had gone into the freezer for those 20 lines. The exclusivity of this encounter indicates the favour which Achilles enjoyed in the goddess’ eyes. But how did she effect this intimate theophany? Did she obscure the vision of the other members of the war council or did she enhance Achilles’ eyesight? Either way, she seems momentarily to have turned them to stone.

The Rage of Achilles, Athena grabbing him by the hair to prevent him from slaying Agamemnon, by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1757) Villa Valmarana ai Nani (Public Domain)

Observing a deity face-to-face, as Achilles does, is often more than human strength can bear, comparable to looking directly at the sun, since the eyes of a deity emit a blazing, blinding light. The effect would have been convincingly suggested by the pool of water in front of the chryselephantine statue of Athena Parthenos that stood inside the Parthenon, towering 36 feet high, in which the reflection of the goddess’ gold helmet, gold breastplate, gold spear, and gold shield shimmered and glistened, particularly at dawn in mid-summer when sunlight flooded the temple through its open doors. It is often better, therefore, for deities to communicate with humans by word of mouth, since, as Hera observed in the Iliad, “The gods are hard to gaze upon in their full brightness.” At the end of Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus, Theseus shields his eyes at the moment when the blind Oedipus is mysteriously conveyed from this world to the next, presumably by an unidentified deity who has been urging him not to delay, “as if some dreadful sight had appeared, which was not to be seen.”

In the Iliad even though Aphrodite disguises herself as an old woman, Helen recognizes “the beautiful neck, lovely bosom and flashing eyes’’ of her protective deity. In the Odyssey Athena does not appear to Odysseus in her true form but assumes the appearance of a mortal woman, “beautiful and tall and accomplished in glorious handicrafts.” However, the fact that she barely conceals her true identity is a measure of the extent to which she favours Odysseus. In Sophocles’ Ajax Odysseus recognizes Athena by her voice, whereas she herself is only “dimly seen,” perhaps so as not to blind him.

Athena showing Ithica to Odysseus, by Giuseppe Bottani (1775) (Sailko/CC BY-SA 3.0)

This same principle holds true for other religious systems, which credit only the spiritually elect with the entitlement to see the divine. It is a mark of their intimacy that in the Book of Exodus the Lord speaks to Moses “face to face, as one speaks to a friend,” though whether one should take this literally seems doubtful. This honour is granted to him only after they have developed a relationship built on mutual respect, since Moses was at first by no means thrilled to have been commissioned to lead the Israelites out of Egypt. Job, presumed author of the Hebrew book of that name, refused to curse God despite all the misfortunes that God had inflicted upon him and is credited with saying, “After my skin has been destroyed, then in my flesh I shall see God,” though very likely these lines are textually corrupt (Job 19:26).

Theophanies continued to be recorded down through the proverbial ages. Herodotus reports that when Pan “falls in” with Pheidippides on Mount Taygetos after his fruitless attempt to enlist the help of the Spartans, the goat god addressed the runner by name and informed him he would support the Athenians in their forthcoming battle against the Persians at Marathon. When St. Peter was visiting Caesarea Maritima in modern-day Israel, a recent convert fell at his feet and did obeisance, whereupon the apostle ordered him to stand up and admonished him, “I am not a god.” After St. Barnabas and St. Paul had performed a miracle at Lystra in modern-day Turkey, the crowd shouted out, “The gods have come down to us!” and hailed them as Zeus and Hermes. How very embarrassing for all concerned.