The Floating Warhorses of Alexander the Great: The Menacing Mount of the Macedonians

The rider must have a firm seat when going at full speed over all sort of ground

and must also be able to use his weapons well on horseback. (Xenophon, On Horsemanship, 8)

When Philip II came to the throne of ancient Macedon in the turbulent days of 359 BC, the nation was besieged. Illyrians were amassing to the north, Greeks occupied the major coastal cities, Thracian tribes and Persian gold were vying to topple the state to install a puppet regime. The young Macedonian king had three survival options: marry daughters of hostile warlords to forge new alliances, bribe his way out of trouble, or develop an army that could repel any foreign menace. Philip’s holistic strategy employed all three.

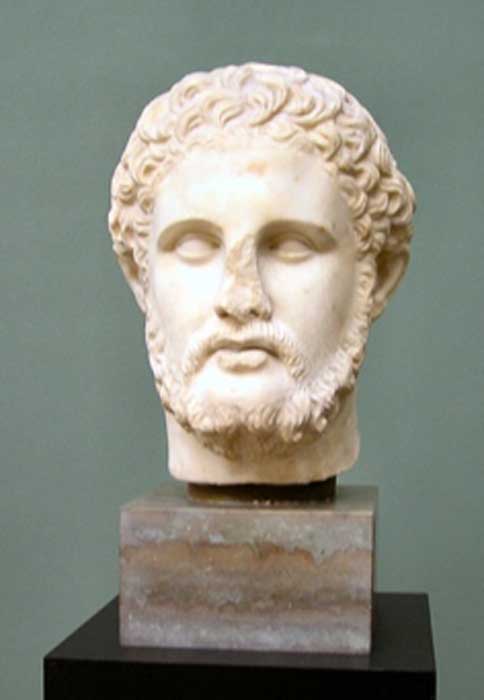

Philip II of King of Macedon, a Hellenistic-era sculpted bust, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek (Public Domain)

Philip’s Vision and Legacy

Through the next 20 years of his consolidating power, which culminated in the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC and absolute control of Greece, Philip trebled the landmass under Macedonian control and raised its income many-fold, principally from occupied gold and silver deposits and mines. His most enduring legacy, however, apart from his precocious son who was destined to conquer Persia, was his reform of the state’s military. Arguably the most notable advance was the revised role of cavalry.

The exiled Athenian combatants and historians Thucydides and Xenophon provided a picture of the early composition of the Macedonian army in the previous century during the reign of King Perdiccas II (448-413 BC) which overlapped with the Peloponnesian War, a conflict which had itself shaken up tactical thought. The military comprised a small accomplished corps of cavalry - principally used in ancillary roles such as scouting and skirmishing, however - a modest number of hoplites, and a more numerous force of light troops from domestic tribes or client princes, still brigaded by tribe as Nestor advised in the Iliad. This was all set to change.

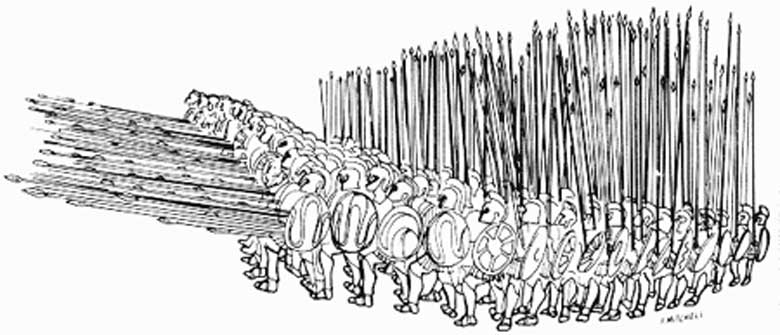

A drawing of a Macedonian phalanx. F. Mitchell, Department of History, United States Military Academy (Public Domain)

The Day the Hoplite Died

As a teenager, Philip had been a hostage at Thebes in the reign of his oldest brother, Alexander II, at a time when Theban military innovators had gained primacy in Greece following victory over Sparta at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC. There a reinforced 50-deep infantry ‘wedge’, headed by the 300-strong Theban Sacred Band under Pelopidas, broke through the ‘invincible’ Spartan crescent phalanx. Pelopidas next employed Greek cavalry against Thessalians at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 364 BC, exploring their previously unused potential. The result was that during his tenure at Thebes, Philip not only learned to compose and speak with the rhetorical arts perfected in Athens, he began developing his own thoughts on the almost ritualized battlefield tactics that had adapted little over the previous centuries.