The Trials And Tribulations Of Arabian Warrior Queens

In the 12th century BC, the collapse of the complex state system in the Near East led to the rise of ethnic group cohesion that had previously been largely fragmented. These ethnic groups morphed into political units which were mostly organized along ethnic‐tribal lines. They included the Phrygians, Hebrews, Aramaeans and the Arabs. The large-scale introduction of domesticated camels in southern Syria and on the Arabian Peninsula allowed the Arabs to traverse the desert that had been previously impassable and therefore engage in a newly emerging international trade in spices, precious materials, as well as in politics. In the ninth century BC, when the Assyrians expanded their military force beyond the Euphrates River, they came into contact for the first time with groups of Arabs who had infiltrated the Levant from northern Arabia and the Syrian desert. Soon after, they were interacting with Arabs on a regular basis in military, political and trade matters.

Domesticated camels gave rise to trade opportunities. A Marketplace in Ispahan by Edwin Lord Weeks (1849 – 1903) (Public Domain)

Assyrian And Arab Contact

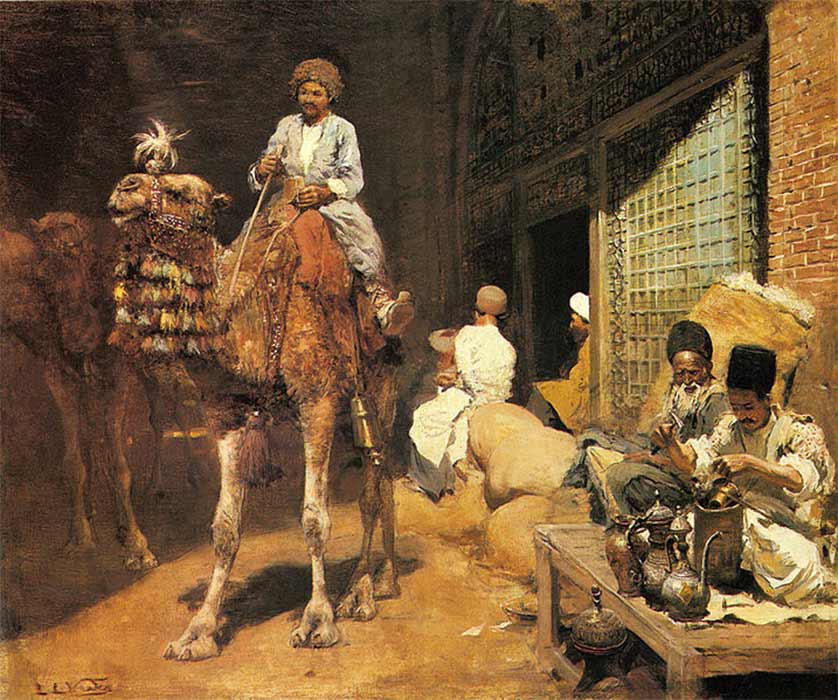

The earliest reference to the Arabs in any written source is found in an inscription on the Kurkh Monolith where the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (858 – 824 BC) describes a battle he fought in the vicinity of Qarqar in 853 BC. A mid‐eighth century cuneiform inscription commissioned by Ninurta‐kudurri‐uṣur, a šakin māti (governor) of Suḫu and Mari in the middle-Euphrates region, tells of a ruler who had organized a raid on a caravan “of the people of Tema and Šaba” and took camels, wool and precious stones as booty. This is the first cuneiform reference to the important city of Tema, a commercial hub and religious centre in the Hejaz in western Arabia.

Kurkh stele of Shalmaneser III from Diyarbakır, southern Turkey. British Museum. (Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin/ CC BY-SA 4.0)

Years later, the western expansion of Assyria under the rule of Tiglath‐Pileser III (744–727 BC) again brought Assyrian troops into direct contact with the Arabs. After his annexation of Unqi and Ḫatarikka in 738 BC, Tiglath‐Pileser III received tributes from numerous rulers from the southwest, including Zabibe, Queen of the Arabs. Five years later, he campaigned against another Arab queen, Samsi. He burnt her tents and seized goods from her as booty to consolidate his control over southern Syria. Realizing that he did not have the means to eliminate Samsi’s tribal proto‐state, Qedar, which was centered in and around the Wādı ̄ Sirḥān in northern Arabia, he allowed Samsi to remain in office, providing her with an Assyrian qep̄ u (political agent) to monitor her political moves.

Palace, Til Barsip. King Tiglath-Pileser III giving audience. (Public Domain)

Zabibe and Samsi were the first of six women who, according to Assyrian royal inscriptions, served as Arab šarratu (reigning queens) from the reign of Tiglath‐Pileser III to that of Assurbanipal who reigned between 669 to 631 BC. As the title šarratu in Assyrian texts refers to reigning queens and goddesses only, not to the main wives of kings, there can be no doubt that these women played a pivotal political role. Although records of their exploits are few and far between, those which tell about these women showed them not only as warriors and effective leaders, but also as astute administrators and negotiators.