Freud the Sleuth, Investigates Who Killed Moses?

Sigmund Freud’s article ‘Moses an Egyptian’ caused an outcry as he was taking the radical view that Moses was not a Jew and ascribing an Egyptian ancestry to the prophet, amid a time when Nazi’s were pursuing Jews, including Freud himself. In his controversial investigation, Freud opened the question: “Who Killed Moses?” that authors Rand and Rose Flem-Ath seek to answer in their book.

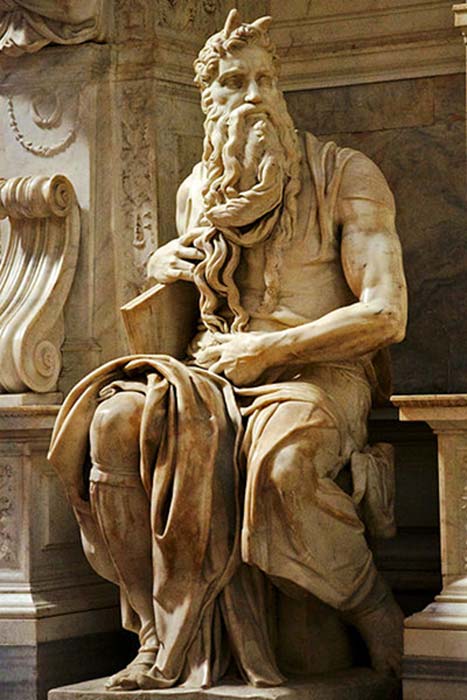

Michelangelo's Moses in San Pietro (Luca Volpi / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Freud’s Nightmare

March 22, 1938 was the worst day of Sigmund Freud’s life. All the loving father’s prestige could not help his daughter now. His beloved Anna was with the Gestapo. In view of the desperate circumstances, the family doctor had slipped Anna a supply of the barbiturate Veronal. If there was no rescue from the Nazis, the drug would provide the girl with the ultimate escape of suicide. Puffing constantly at a cigar, the father waited, pacing the floor like a caged animal. But Anna Freud had inherited a cool intelligence and a stoic self-discipline that would save her life. Inside a cold corridor at Gestapo Headquarters she gambled everything by pushing forward to the head of the line of detainees waiting to be interrogated. The method behind her madness was driven by the terrifying certainty that if she hesitated until the day’s end the Nazi bureaucrats would sweep up those remaining in the queue like litter and dispatch them to a concentration camp. There would be no returning the next day to take care of unfinished business.

Sigmund and his daughter Anna Freud. United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division (Public Domain)

Anna’s bold strategy worked and to the relief of her anguished father she found her way back through the streets of Vienna to the home where her family had lived for 47 years. The reality that the bullying, terrorizing, and murdering of Jews had become a psychopathic sport had hit home. SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler had been constantly braying for Sigmund Freud’s imprisonment. The American consul general, John Cooper Wiley, intervened to buy the famous analyst some time, but Freud feared he was too old and weak to make the transition to a new life and he doubted that he would be granted the precious permit needed to settle in another country. But his daughter’s chilling experience accomplished what the burning of his books in Berlin and even the brutal German occupation of Austria could not; it changed Freud’s mind about the wisdom of remaining in his homeland.

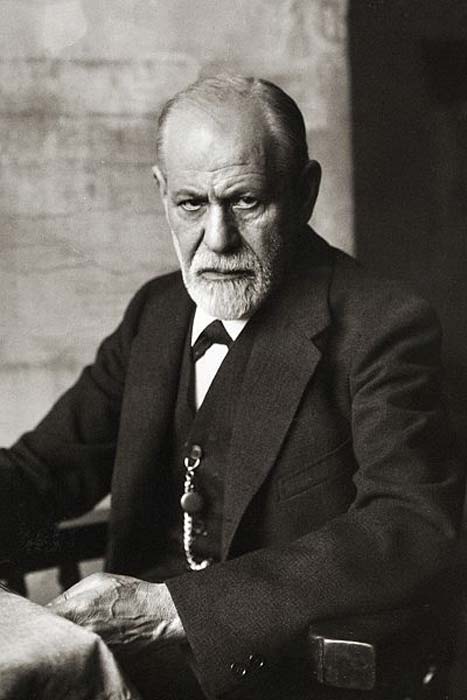

Sigmund Freud in 1926 (Public Domain)

The Nazis did nothing to ease his transition. Their perverse ‘certificate of innocuousness’ was designed to rob any potential emigrant of their entire financial means. It was enacted with excruciating precision and guaranteed that the target would only escape the regime with little more than the clothes on their back. While Freud endured the wait for his exit visa, he revisited his collection of books and a lifetime’s worth of papers. Despite overwhelming stress and the pain of a terminal illness (Freud had been diagnosed with cancer of the palate) he could not give up his obsession and worked at least an hour a day on Moses and Monotheism. After three months of anxiety he was finally granted permission to leave Austria. But not before his signature was demanded on a statement testifying that he had suffered no ill treatment from the Nazis.