Historical Overview Of Chinese Women Warriors

It comes as no surprise that stories about women's involvement in wars pique people's interest all over the world. Apart from challenging fundamental gender norms through their daring deeds and dramatic actions, the mere image of a woman killing another human being calls into question long-held beliefs about women as life-givers rather than death-bringers. The sight of graceful and delicate female bodies in military uniforms challenges conventional notions of feminine beauty and grace, and the idea of women putting their lives in danger defies the notion that such bravery is primarily a masculine trait. All these images beg the question, "How can a woman ever presume to participate in battle?”

A Southern Song painting depicting the male generals who stopped the Jin advance into southern China. (Public Domain)

An enduring image reinforced by countless war movies is that of women sending their men off to war from the family home's doorstep and then waiting for them to return once victory is secured. The masculinity of the war in which soldiers are expected to participate is centered on the basis of protection of women and their sexual virtue. This placement of women who “need to be defended” thus isolates the feminine in a distinct social space and heighten the masculine world of the soldiers' barracks. Women warriors upend this rather neat distinction by blurring the lines between the traditional demarcation of war space. Thus, instead of the very clear distinction of women at home and men in the barracks, the barracks also become a place where women can live, just as much as the home is a place where men can take refuge.

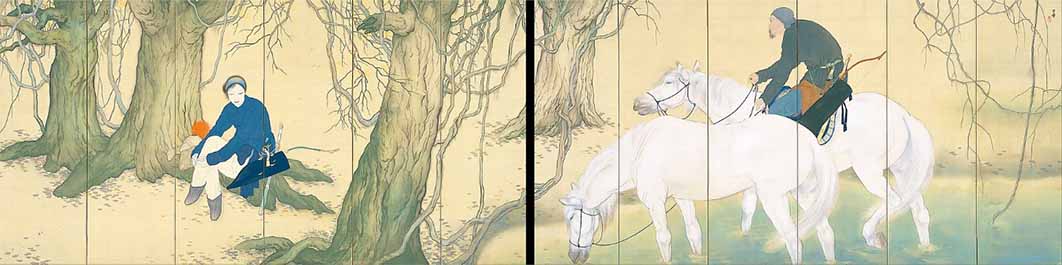

Hua Mulan resting with her sword beside her, by Kansetsu Hashimoto (Public Domain)

Hua Mulan Defending Her Family’s Honor

The tale of Hua Mulan is a clear example of this as, due to her father being too old and her younger brother being too young, she decided to take her father’s place in the war. Her father, therefore, stayed home as Hua Mulan went to war. Hua Mulan exemplifies that some women simply do not regard themselves as potential victims to be rescued. These women seek active roles which in turn challenge the gendered principle that war increases men's masculine power by affording them the role of protector of women and their virtue. Hua Mulan rejected a system that would reduce her to a sexual integrity symbol, at the same time demonstrating her filial piety to her father and her family’s honor.

Actress Zhou Zhiru playing Xun Guan in a Peking opera performance at the Tianchan Theatre (CC BY-SA 2.5)

13-Year Old Warrior Girl Xun Guan

Xun Guan, who lived during the Western Jin Dynasty (265 - 316 AD) had an impressive lineage. She was the daughter of Xun Song, the governor of Xiangyang. Her father was the great-grandson of Xun Yun, son of Xun Yu (163–212 AD), the adviser to the Han Dynasty warlord Cao Cao (155 – 220 AD). It was on Xun Yu’s suggestion that Cao Cao decided to escort Emperor Xian, who was then living in the ruins of Luoyang, to his own base at Xu (present day Xuchang, Henan province) in 196 AD, thus taking on the role of the emperor’s protector. His role literally means “Obey the Son of Heaven (the emperor) and order no ministers”. His intention was noble as he positioned himself close to the emperor, expressly to assist him and claimed no power for himself to lord over the emperor’s subordinates or nobles. Instead, Cao Cao’s role was to control the insubordinates in the name of the emperor. This tactic of Xun Yu was immortalized in the 14th-century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, although the novel subtly distorts this intention as holding the emperor hostage to control the nobles. Nevertheless, thanks to Xun Yu’s strategy, Cao Cao gained a considerable political advantage over his rivals, allowing him to legitimise his actions by eliminating them in the name of the emperor.