Wuxia The Underdog Chinese Martial Arts Hero And The Code Of Jianghu

Those who are familiar with the Chinese word wuxiá (martial heroes) may associate it with memories of martial arts films and television programs that portray a fanciful depiction of Chinese martial arts to audiences around the world. However, there is more to wuxia than meets the eye. Wuxia is in fact an entire literary genre that depicts the exploits of ancient Chinese martial artists. It has proven to be popular enough to feature in a number of modern cultural media, including Chinese opera, films, television series and video games.

Depiction of fighting monks demonstrating their skills to visiting dignitaries (early 19th-century mural in the Shaolin Monastery) (Public Domain)

Origins Of Wuxia

In general, wuxia is a narrative about heroes. But the heroes in wuxia rarely serve a ruler, wield military power, or belong to the aristocracy. In fact, they are frequently descended from the lower social classes of ancient Chinese society. The chivalric code upheld by the hero typically requires heroes to right and redress wrongs, fight for righteousness, remove oppressors, and bring retribution for previous wrongdoings.

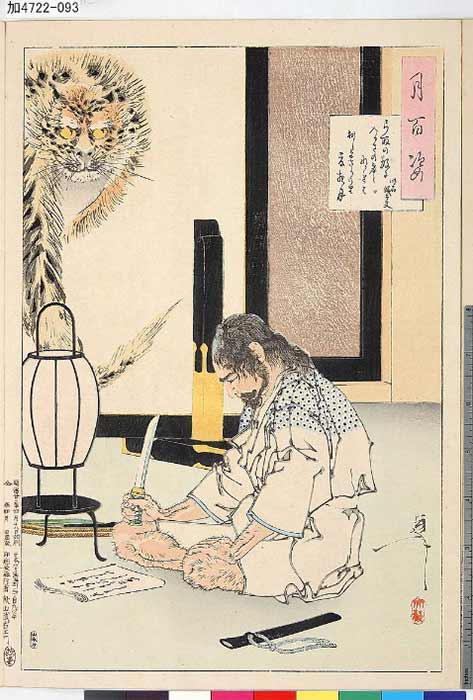

General Akashi Gidayu preparing to commit Seppuku after losing a battle for his master in 1582. He had just written his death poem, which is also visible in the upper right corner. Tokyo Metro Library (Public Domain)

Despite the fact that the term wuxiá as a name of a genre is a recent innovation, martial arts tales date back over 2,000 years tracing their roots all the way to ancient Chinese warrior folk tales known as youxia (wandering vigilante) which were glorified in classical Chinese poetry and fiction. In this context, the Chinese xia traditions are comparable to martial arts codes from other cultures such as the Japanese Samurai bushido which formalized earlier Samurai moral values and their ethical code. With the ascent to power of the warrior caste at the end of the Heian period (794–1185) and the founding of the first Kamakura shogunate, sincerity, frugality, loyalty, martial arts mastery, and honor until death were all stressed by bushido. It is a code which allowed the violent existence of the Samurai to be tempered by the wisdom, patience and serenity cultivated by the Samurai themselves.

Portrait of Han Fei by an unknown author (Public Domain)

In his chapter of five social classes in the Spring and Autumn Period (the chapter is called On Five ‘Maggot’ Classes), Legalist philosopher Han Feizi (c. 280 – 233 BC) spoke disparagingly of the youxias. As he was a member of the governing nobility, having been born into the Han State's reigning dynasty during the Warring States period, it is possible that Han Fei demonstrated his disdain of youxia because it was popular among the lower social classes. In an essay on the essence of the six schools of thought, Sima Tan (d. 110 BC) notes that fa jia (legalism) are “strict and have little kindness,” and “do not distinguish between kin and stranger, nor differentiate between noble and base: everything is determined by the standard (or law, fa).” Therefore, taking this into consideration, it is also possible that Han Fei disapproved of youxia because, in his view, it did not adhere to the strict standard of legalism that he upheld.