The Zeno Map And Travels Of the 14th-Century Venetian Zeno Brothers

A century before Columbus, at the zenith of Venice's splendour, two brothers, Nicolò and Antonio Zeno embarked an extraordinary journey to the far north following Viking trade routes on the shores of Canada. The travel log of the 14th-century Venetian brothers, which included the now famous Zeno map showing mysterious islands, and made reference to a mysterious benefactor Prince Zichmni, was discarded as a hoax, until recently new investigations. Who were these extraordinary men, what did they discover and why was their story subjected to damnatio memoriae since the 19th century?

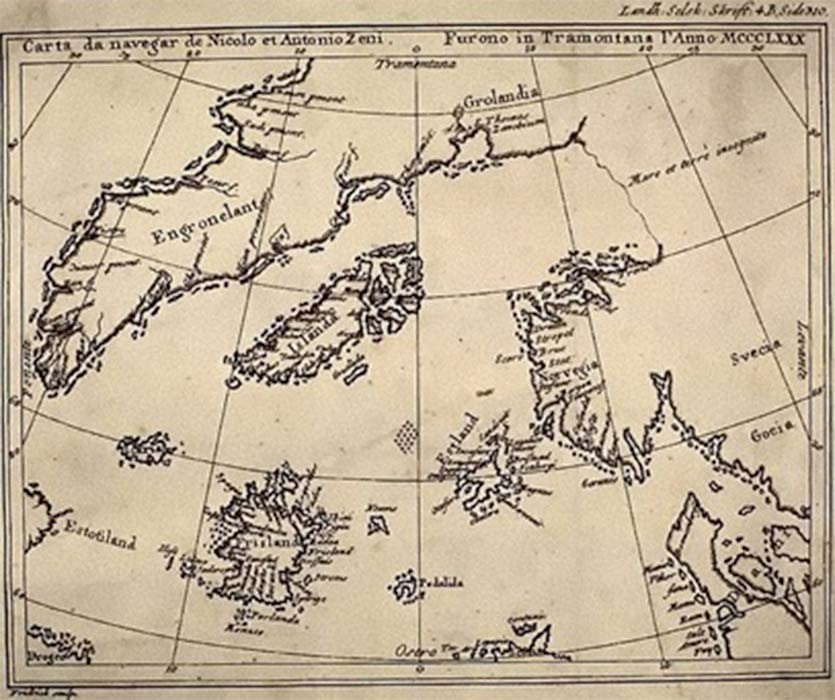

A reproduction of the Zeno map from a 1793 book (Public Domain)

The Zeno Map

The Biblioteca Marciana in Venice, in St. Mark's Square, holds a book dated to 1558, Dello Scoprimento dell’Isole Frislanda, Eslanda, Engroneland, Estotiland et Icaria fatto sotto il Polo Artico da due fratelli Zeni, (About the discovering of the islands of Frisland, Esland, Engroneland, Estotiland et Icaria made under the Arctic Pole by two Zeno brothers) published by Francesco Marcolini. In the introduction he explains that the narrative was written by Nicolò Zeno the Younger, great-nephew of Antonio and Nicolò Zeno, the two navigators whose travels are described in the text. Nicolò Zeno the Younger reports that he found five long letters of his ancestors in the family library and that he was able to proceed with a careful editing of their story, adding parts of the missing text on his own to connect the passages of the letters. With regret he adds that, having found them as a child in the family library and not comprehending their value he had irreparably ruined them so that a considerable part of the information was lost.

Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana (Public Domain)

Venice had become the world capital of publishing in the 16th century and travel logs were always confirmed among the most successful books: Nicolò the Younger wanted to add prestige to his family name by publishing the exploits of his ancestors. He added a nautical map in the style of the time (carta da navegar) to the text, which came to be known in history as the Zeno Map.

It is a typical map of the 14th-century which clearly distinguishes Norway, Sweden, Greenland and Iceland, as depicted by the respective place names on the map. But what differentiates this map are the mysterious islands that nobody had heard of at the time: Friesland, Icaria, Estotilanda, and even the coasts of the Newfoundland area in today's Canada and parts of the southernmost areas. However, the map contained obvious positioning errors in latitude and longitude, so that some islands later found in reality were not at their designated geographical coordinates. Nonetheless, the book had some success and several editions began to spread, which came into the hands of Gerard Kremer, the great cartographer better known as Mercator, who was intrigued and used the Zeno Map for his Modern Map of the World (1569). Because of this the mysterious islands of the Zeno Map continued to be represented in nautical maps for some time.

The Enigma Of Frislanda

Friesland continued to remain a mystery to navigators until 1787, when the French geographer Jean Nicolas Buache in his study Mémoire sur l'isle de Frislande observing the approximate latitude of the island suggested the possibility that it was the archipelago of the Faroe (or Feringian) Islands. Later the German geographer Henrich Peter von Eggers confirmed the hypothesis by comparing Marcolini's text with the place names of the Faroe Islands: Munich for Munk, Sudero for Sutheroy, Nordero for Norðadalur, Andeford for Arnafjord, and others. The Viking colonization of the islands took place around the ninth century and the archipelago was called Faeroe Island, the island of sheep.

The conclusion reached by scholars is that Nicolò Zeno, writing his letters, contracted the name, probably pronounced quickly, in Medieval Venetian: Faroe island/Friesland/Frieslanda. This hypothesis seems to be the most interesting and probable.