Common Cosmic Symbolism: Is Göbekli Tepe Ancestral to Ancient Egypt?

- By Martin Sweatman

- 1

Since its discovery in 1994, 10,000-year old Göbekli Tepe has been an enigma, gradually revealing its ancient secrets to archaeologists and scientists. Meticulously excavating the site from soil that has covered it for thousands of years, so they metaphorically uncover and decipher the mystery of this sophisticated culture. Scientist Dr Martin Sweatman translates pillar 43, aka the Vulture Stone, as probably memorializing a globally catastrophic comet impact circa 10,900 BC, and he then follows their trail through the Levant to ancient Egypt, guided by common cosmic symbology and ancient DNA.

The ‘Fertile Crescent’ in the early Neolithic period, incorporating the Egyptian Nile, the Levant, southern Anatolia, and Mesopotamia. (Image: Martin Sweatman)

Ancient Linguistic Proto-forms

Linguistic scholars like to study the similarities between different languages to see how they are connected. In this way, they can trace the origin of a group of similar languages to an earlier ‘proto-form’. This approach, known as comparative linguistics, complements the study of the evolution of human genetics, or ancient DNA, for tracing the migration of groups of people.

It has come to be generally accepted by linguists that hundreds of ancient languages and mythologies across Eurasia derive from an even more ancient culture, circa 3,500 BC, known as Proto Indo-European (PIE). This view is strongly supported by studies of ancient DNA, that show that the founding PIE population came from a region to the north of the Black Sea, modern-day Ukraine.

Göbekli Tepe site showing different sections (Teomancimit / CC BY-SA 3.0)

Likewise, there is general acceptance of a similarly ancient culture connecting languages and mythology across North Africa and South India, known as Proto Afro-Asiatic. But the possibility that both these ancient proto-cultures could have originated and dispersed from an even more ancient founding culture in the Levant (as strip of fertile land at the eastern end of the Mediterranean), known to scholars as Proto Nostratic, circa 12,000 BC, is not widely accepted, despite strong support from some of the world’s foremost linguists. For many other linguists, the evidence is just not strong enough and the methods used to derive the Proto-Nostratic language are questionable.

Archaeological Anomaly Göbekli Tepe

Göbekli Tepe adds much fuel to this fire. Discovered in 1994 by Klauss Schmidt in southern Anatolia, Göbekli Tepe continues to turn academic paradigms inside-out and upside-down. With its dozens of magnificent stone circles that pre-date Stonehenge by over 6,000 years, finding a site like Göbekli Tepe was a complete surprise. This makes it an archaeological anomaly of the utmost importance. The earliest radiocarbon date for the small portion of Göbekli Tepe excavated so far is around 9,600 BC. But given that one of its megalithic pillars, Pillar 43 – aka the Vulture Stone, very likely memorializes a globally catastrophic comet impact circa 10,900 BC, further excavations are likely to uncover even older remains.

Ancient Site of Göbekli Tepe in Southern Turkey (Brian Weed/ Abode Stock)

Göbekli Tepe is said to be the world’s first temple. Very likely, it was also an observatory for monitoring the Taurid meteor stream, from whence this nefarious comet came. Whatever its precise function, its location and timing suggest it is pivotal in the origin of civilization. They also make it a perfect candidate for the putative homeland of Nostratic. Perhaps its discovery can resolve the thorny Nostratic debate?

If the Nostratic hypothesis is correct, we should find strong links, at least in terms of writing and mythology, between symbolism at Göbekli Tepe and that found in many surrounding cultures across Eurasia and North Africa. I discuss this possibility in my recent book Prehistory Decoded, but here I want to focus specifically on the cultural links between Göbekli Tepe and Ancient Egypt (an Afro-Asiatic culture), which appear to be especially strong.

- Banduddu: Solving the Mystery of the Babylonian Container

- The Lost Legacy of the Super Intelligent Denisovans Who Calculated Cygnocentric-based Cosmological Alignments 45,000 Years Ago

- Music, Math, Megaliths and the Dawn of Humanity

These two cultures are separated by nearly 500 miles and, more importantly, over 4,000 years, yet their similarities are uncanny. It’s almost as though the people of Göbekli Tepe are the direct ancestors of the Ancient Egyptians. Could this be true?

Archaeological excavations uncovering Göbekli Tepe from mountains of earth (view / Abode Stock)

Symbolic Links Between Göbekli Tepe and Ancient Egypt

Göbekli Tepe was finally abandoned and covered over with mountains of earth and waste around 8,000 BC. But its decline as a cultural center is apparent for millennia before this. It seems there was a gradual shift of population from Göbekli Tepe to other places. But where did these people go? Why would they leave the greatest monument of their age in the dust? Is it possible they left Göbekli Tepe for the fertile banks of the Nile? Perhaps life was much easier there.

Strangely, there is no clear sign of human habitation along the Egyptian Nile until around 6,000 BC. From this point onwards, archaeologists find a gradual increase in settlement along this section of the Nile, beginning with isolated villages leading eventually to the mighty Egyptian Dynasties, around 3,000 BC. So, if the Ancient Egyptians do derive from a more ancient source near Göbekli Tepe, where did they go between 8,000 and 6,000 BC? And why do they appear to have taken several steps backwards along the civilization score track during this time? What happened to them? Whatever the case, the cultural similarities between Göbekli Tepe and Ancient Egypt deserve to be highlighted.

Göbekli Tepe’s ancient megalithic pillars (muratart / Adobe Stock)

The transference of skills in megalithic architecture seems the most obvious. There is little to challenge the grandeur of Göbekli Tepe’s ancient megalithic pillars until the emergence of higher civilizations in Mesopotamia and Egypt in the fourth and third millennia BC. However, ancient Jericho, in modern-day Palestine, with its tall stone towers and thick city walls that date to around 8,000 BC, bucks this trend. Possibly, the southern Levant was an intermediary step for the people of Göbekli Tepe on their way to Egypt?

Top of Pillar 33 (Klaus-Peter Simon / CC BY-SA 3.0)

But it is their shared astro-mythological symbolism that appears to provide the most direct link, with, curiously, no indication of any intermediate repository. My recent research decodes Göbekli Tepe in terms of an ancient zodiac, where animal symbols represent star constellations - the same constellations that make up the western constellation set that we continue to use today. Snake symbols are an important deviation - they very likely represent meteors, specifically from the Taurid meteor stream.

Pillar 43 (Public Domain)

For example, consider Pillar 43, Pillar 2 and Pillar 33, with their many animal symbols, at Göbekli Tepe. Now consider some of the most important Ancient Egyptian deities. Does the eagle/vulture on Pillar 43, representing Sagittarius, become Horus (a falcon-headed god) in Ancient Egypt? This would make sense given the Ancient Egyptian’s known fascination with astronomy. In fact, astronomy was quite literally their religion.

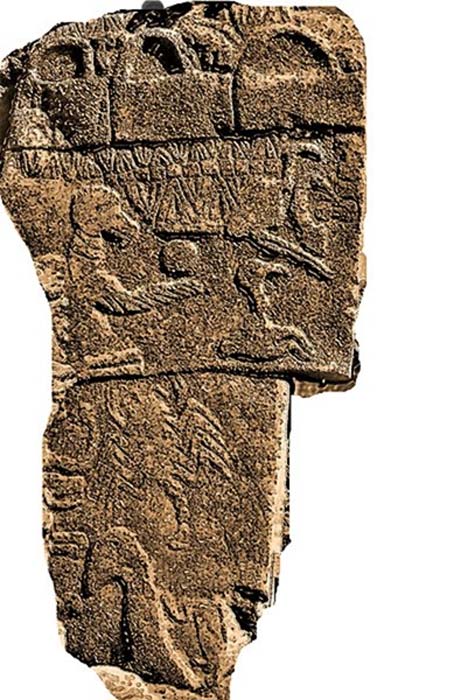

Evidence for this association can be found on a jar discovered in a pre-dynastic tomb at Abydos.

The tomb is thought to belong to an Egyptian ruler, or warlord, known as the Scorpion King. The reason for this is precisely because of a scorpion symbol appearing on this jar beneath a bird-of-prey symbol, thought to represent Horus. And, as the Horus symbol normally precedes the names of Pharaohs in Dynastic times, this jar is thought to have belonged to the Scorpion King. But Egyptologists have no explanation for the appearance of a goose symbol on this jar beneath them both.

Hierakonpolis cylindrical limestone vase with the eagle/scorpion/ goose motif. (Public Domain)

But, it is clear that the symbols on this jar imitate those on the main panel of Pillar 43, where we see the vertical sequence eagle/vulture-scorpion-goose, representing Sagittarius-Scorpius-Libra. In fact, the symbols on this jar, using the new zodiacal theory, can instead be interpreted as the date 3,500 BC, to within a few hundred years, which agrees well with other archaeological evidence for the date of this tomb.

Pillar 2 (Klaus-Peter Simon /CC BY-SA 3.0)

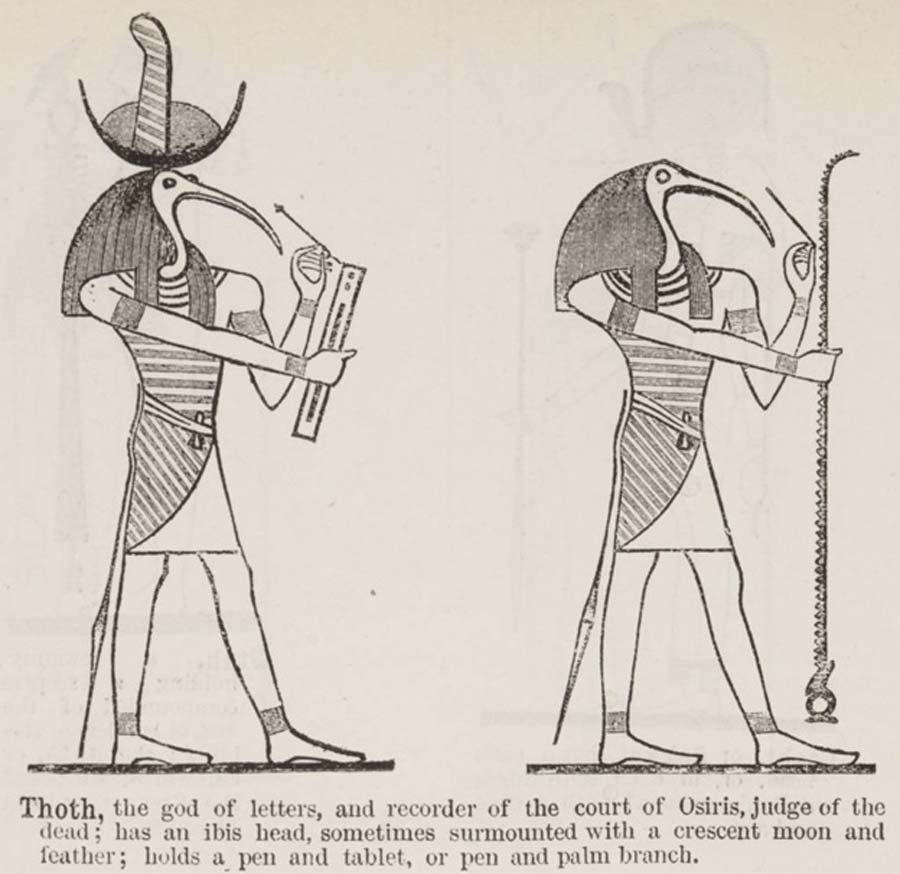

In a similar way, it appears most of the other major Ancient Egyptian deities are descended from known constellations. For example, Thoth, the god of knowledge and writing, resembles the tall bird symbol, representing Pisces, seen at the bottom of Pillar 2 at Göbekli Tepe. And Anubis, Ancient Egyptian god of the underworld and embalming, resembles the dog/wolf on Pillar 43, representing Lupus. Meanwhile, the fox symbol at Göbekli Tepe, also seen on Pillar 2, probably became Set, the Egyptian deity of desert storms and chaos. This is highly appropriate, as the fox at Göbekli Tepe represents the constellation Aquarius, which would have been the constellation from which the Taurid meteor stream appeared to emanate. Indeed, Pillar 2 can be interpreted as the entire path of the radiant of the Taurid meteor stream when Göbekli Tepe was occupied, from Capricornus through Aquarius to Pisces.

Thoth (in Illustrated List of the principal Egyptian Divinities) (1888) (CC BY-SA 2.5)

The aurochs, or bull, symbol on Pillar 2 representing Capricornus (not Taurus) is also likely associated with the death and destruction of the Taurid meteor stream at this time. Quite possibly, this symbol evolved to become one or all of the many cow deities in Ancient Egypt, including Apis (who represents death and sacrifice) and Hathor (who represents the dual roles of fertility and destruction). The lion/leopard symbol, meanwhile, probably representing the constellation Cancer (not Leo) at Göbekli Tepe, becomes various lion and leopard deities in Ancient Egypt, from Sekhmet to Seshat.

Finally, let’s consider Amun, the patron deity of Thebes (within modern-day Luxor). Because of Thebes’ rise to pre-eminence in the Middle and New Kingdoms, he came to be seen as the chief creator deity – the foremost deity of all Ancient Egypt. Now, it’s very interesting that during his Middle Kingdom reign, Amun was typically associated with a goose and was pictured with a pair of goose feathers on his head. But then, by around 1,500 BC in the New Kingdom, he was more often linked with the ram. It is probably no coincidence that at this time the goose symbol, corresponding to Libra, was the Autumn equinox constellation while the ram symbol, corresponding to Aries, was the Spring equinox constellation. It appears, then, that in the switch from Middle to New Kingdoms, the spring equinox became more important than the autumn one, and therefore Amun’s symbol switched from goose to ram.

Egyptian - Model of a Vulture and Uraeus Seated on a Basket (Walters Art Museum) (Public Domain)

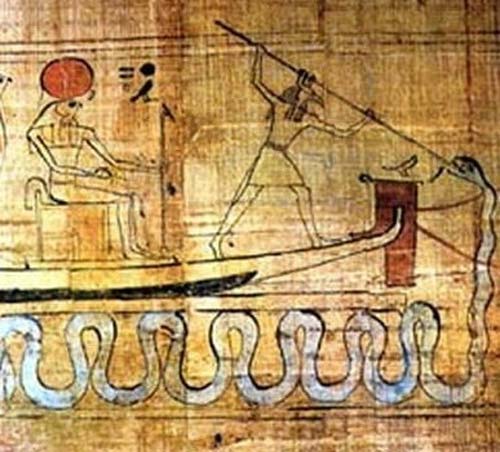

But what about snakes. As already mentioned, these almost certainly represented meteors at Göbekli Tepe. Klauss Schmidt, who lead excavations until his death in 2014, himself suggested a connection between these snake symbols and the serpentine Uraeus symbol of Ancient Egypt, which represents god-like power. I suspect they are also the forerunners of Apep, the Ancient Egyptian cosmic chaos serpent. Indeed, Apep is said to have a head of stone, like a meteorite.

Probably there remain many more connections like this to be uncovered. However, let’s now turn to the vexed issue of the origin of writing.

The Origin of Writing

Proper writing, which is essentially just the visual representation of speech, appears for the first time almost simultaneously in Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt around 3,000 BC. The general view, it appears, is that writing developed out of symbols used to represent trade.

But Göbekli Tepe challenges this view. We see symbols and methods used at Göbekli Tepe that appear 5,000 years later in pre-dynastic Egypt almost unchanged. And then, within perhaps just a few generations, proper hieroglyphic writing is found in the ruins of the first few Egyptian dynasties.

Left to right: Pillar 2 at Göbekli Tepe, an Ancient Egyptian cartouche, and a stone plaquette found at Göbekli Tepe (images courtesy, Klaus-Peter Simon /CC BY-SA 3.0, Cartouche of Thutmose III CC BY-SA 2.0 and Alistair Coombs respectively).

For example, consider the cartouche, which is used to write important names in Ancient Egypt using hieroglyphs. A cartouche consists of a short series of graphic symbols enclosed by an oval border with a perpendicular line at one end. This is so very similar to how information is represented on the pillars at Göbekli Tepe – see Pillar 2 for example. Perhaps the oval border evolved from the pillar outline while the perpendicular line represents the ground on which the pillar stood.

Also, consider a stone plaquette found at Göbekli Tepe with three symbols. The site’s archaeologists interpret this as simply a drawing of three animals – perhaps a bird, person and snake. But in my view, it is far more likely this scene tells the story of one of the most common myths across the Nostratic world – ‘the sky/storm god attacks and kills the cosmic chaos serpent, who falls to Earth’.

Set spearing Apep. (Egyptian Museum Cairo) (Public Domain)

There are so many versions of this ancient myth in both Indo-European and Afro-Asiatic cultures, from Greek Zeus vs Tython to Egyptian Set vs Apep, Sumerian Marduk vs Tiamat and Norse Thor vs Jormungandr. And, considering that Göbekli Tepe possibly represents a founding Nostratic system of ancient mythology, this plaquette could be the first known telling of the original story.

The trident symbol on the left of this plaquette is often associated with Indo-European sky/storm gods, like Shiva, Poseidon, and even Satan. Considering that Göbekli Tepe memorializes the Younger Dryas impact event, we can now interpret the trident as originally representing a comet god.

Teshub, God of Thunder. Hittite relief from Samal (now Zincirli). Pergamonmuseum, Berlin (Public Domain)

So, we see that the proto-writing at Göbekli Tepe appears capable of more than just representing astronomical observations. The plaquettes and pillars appear to tell stories, and might also represent the names of astronomical objects like the Taurid meteor stream, that eventually become the versatile system of hieroglyphics and cartouches seen in Ancient Egypt.

But while the connections between Göbekli Tepe and Ancient Egypt are tantalizing, it is difficult to be certain of them. Could all these correlations between the animal symbols, constellations, Ancient Egyptian deities, mythical stories and writing methods just be a coincidence?

Logically, there are three possibilities. First, it may well be the case that all these connections can be explained by pure chance. Second, the connections could be real, and result from a process of cultural diffusion, i.e. the spread of useful ideas and conventions over many millennia. Finally, there might well be a direct link, with the people of Göbekli Tepe migrating southward, eventually becoming the ancestors of the Ancient Egyptians.

How can we know which of these possibilities is correct? It will be difficult to decide between cases 1 and 2 until evidence for transitional forms, that span the 4,000-year gap between Göbekli Tepe and Ancient Egypt are found. None are apparent just yet, and in any case their culture appears to have gone significantly backwards, not forwards, over this time. However, if case 3 is correct, we should at least find similarities in the DNA of Ancient Egyptians and the people that built Göbekli Tepe.

A reconstruction of a Natufian burial at the "El-Wad Terrace" archaeological site in the "Nahal Me'arot" Nature Reserve, Israel . (האיל הניאוליתי / CC BY-SA 2.5)

Ancient DNA Link

At the time Göbekli Tepe was built, between 10 and 11 thousand BC, the most advanced known culture in the area were the Natufian. They lived in small permanent settlements in the Levant, just to the South of Göbekli Tepe in southern Anatolia. Therefore, the Natufian, with perhaps some genetic mixing with ancient Anatolians, are prime candidates for the builders of Göbekli Tepe.

Fortunately, exactly the evidence we require has recently been published by Scheunemann et al. in the journal Nature Communications in 2017. They sampled DNA taken from some New Kingdom Egyptian mummies as well as the remains of many ancient people from across the Near East and north Africa. And what they found was very interesting indeed.

The closest genetic link to the Egyptian mummies was with Bronze Age people from the Levant. The near-identical genetic heritage of these people indicates they were in constant contact at this time. However, going back further in time to the original founding populations, we can say, very roughly, that Ancient Egyptian DNA consisted of around 50% Natufian DNA, 30% Neolithic Anatolian DNA, and perhaps 20% Neolithic Iranian DNA (presumably from the Zagros mountains nearby). In other words, the genetic evidence points to exactly the region where we find Göbekli Tepe, whose builders, or at least their descendants, are expected to have this genetic make-up.

Mummy of an upper-class Egyptian male (Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum) (Oleg Alexandrov / CC BY-SA 4.0)

So, the available genetic evidence strongly supports the idea that the builders of Göbekli Tepe were ancestral to the ancient Egyptians, and therefore all these symbolic connections we have noted are real and direct.

But certainty will only come with further discoveries that show what happened to the people who built Göbekli Tepe after they abandoned it around 8,000 BC. Where did they go next? Was it Jericho? If so, why is there no evidence for any settlements along the Nile before 6,000 BC? And why does their culture seem to have been reset, from megalithic temple builders almost to zero?

I discuss a potential solution to this conundrum, that involves the Ancient Egyptian myth of Zep Tepi and the Great Sphinx of Giza, in my book Prehistory Decoded.

Top Image: Göbekli Tepe PIlars in the Sanliurfa museum. (Cobija / CC BY-SA 4.0)

References

Sweatman, M. 2018. Prehistory Decoded, Matador.

Sweatman. M.B. & Coombs, A. 2019. Decoding European Palaeolithic Art: Extremely Ancient Knowledge of Precession of the Equinoxes. Athens Journal of History vol. 5,

Al-Hennawy, H.K. 2011. Scorpions in Ancient Egypt. Euscorpius vol. 119.

Schuenemann, V.J. et al.2017. Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan ancestry in post-Roman periods. Nature Communications vol. 8.

October 30, 2020, 11:34 am

~sanbátu~

Hello, Mr. Sweatman, and thank you for your intriguing article. Your research has shed light on an ancient, ancestral connection between societies that, to me, makes perfect sense. After all, the inhabitants of Göbekli Tepe had to go somewhere.

I wanted to add an explanation of the image of the goose, mentioned as being seen in carvings. The symbol of the goose in Ancient Egyptian artefacts is a reference to the God of Earth, Geb. He is the grandson of Atum, the primeval God of Creation Who is one of the various manifestations of Ra (another form of the God is Amun, also called Amun-Ra). Referrals to Geb, Whose name in hieroglyphs is simply a goose, are common in many Old Kingdom writings that have been found. After the Second Intermediate Period, and especially into the New Kingdom, mentions of Geb were much more rare, with the reference to Geb's son, Osiris, (and especially Horus, son of Osiris) being encountered far more often.

Although I am deeply respectful of your knowledge and work, for me it would be quite a stretch to connect the various animal carvings at Göbekli Tepe to the anthropomorphic representations of the Gods in Ancient Egypt. For one, the artwork at the former site simply depicts animals, without any corresponding symbols indicative of deities. The symbol of the fox is just a fox; it is not behaving erratically, causing unrest or upset to the other animals. Set, however, is the harbinger of chaos, unpredictable and inexplicable events (such as devastating storms), and the harm that is done by those who thirst for ultimate power and control. On a side note, no one has ever identified the exact animal that Set represents, but He is definitely not a fox.

There is also Apep, who is not depicted as a snake in any artwork. At least, he is not shown as a whole snake; pictures or glyphs of the ultimate enemy of Ra are consistently seen as fracturing, dismembering or otherwise destroying the source of evil. There seems to be no Göbekli Tepe carving found (yet) that would suggest a being in complete opposition to all creation.

While it is my opinion that the carvings at the mysterious, fascinating site of Göbekli Tepe are not early examples of the Gods revered by Ancient Egyptians, I find the theory of migration to and subsequent inhabitance of the Nile Valley by these unknown people to be entirely plausible. Whatever their beliefs, practices and system of worship were, it is obvious they were highly active in building monumental structures, in all likelihood to honor their Gods. This would be another trait passed down through generations to the Egyptians.

Thank you, again, for your publications.