The Curious And Precarious Life Of A Medieval Jester

The medieval jester has become an iconoclastic figure in society, regularly appearing in the TV shows, films, and video-games of the modern era. The classic jester, replete with flamboyant colorful dress and a nimble wit to match, was a popular mainstay of medieval courts, which prized the artistic talents and stark honesty of the professional funnyman, delivered with a characteristic comedic flair. The wide range of names given to jesters in a variety of languages illustrated their widespread popularity not only in Europe. Among the English estates they were called menestrels or joculatores’, in France they were jongleurs, in Russia skomorokhi, in India komali, and for the tribes of Tonga, faakaluma. The word ‘jester’ was an Anglo-German construct, emerging in the 16th century from the word gestour which meant ‘storyteller’.

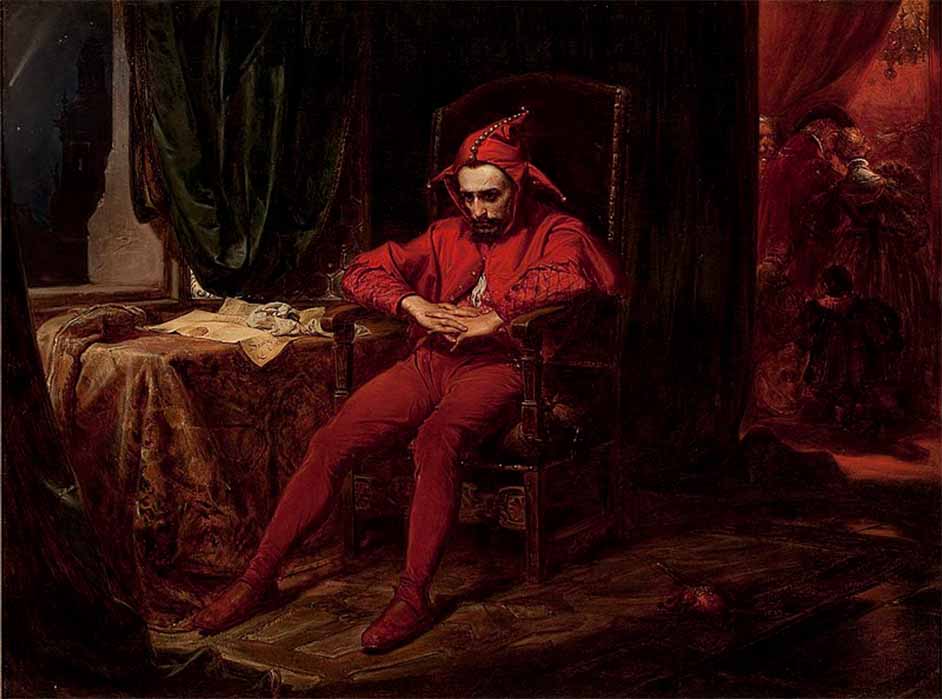

The Jester by Claude Andrew Calthrop (1871) (Public Domain)

Jesters could be found plying their trade in the streets, squares, and palaces of medieval Europe and in realms far beyond. Jesters could be divided into two types: a licensed fool was a person pretending to be a buffoon, but a natural fool was an individual who often suffered from some sort of mental illness to the amusement of noble keepers. In fact, the word ‘fool’ was completely synonymous with ‘jester’ in European courts, however, to call a jester an ‘idiot’ was a mistake. An enormous amount of talent and intelligence was required to become a successful jester, and the lucky few who were good enough could live a comfortable life under the wing of a wealthy patron, providing they were up to sufficient standard.

The Early Origins Of The Jester

After the fall of the Roman Empire, and in combination with the rise of Christian criticisms of entertainment, the theatre as an important dramatic tradition declined. The sixth century witnessed the ascent of the individual entertainer, however these early showmen had to contend with the virulent remarks of Christian writers, who saw in artistic tomfoolery a gateway to Satan.

Woman and a Jester by Adriaen van de Venne (1630) (Public Domain)

Christian writers viewed jesters as sinful and corrupt, and often linked them with the Devil. In the 13th century theologian Guglielmus Peraldus launched a scathing diatribe against the professional buffoon, linking their capacity to make men laugh, a dangerous and sinful action, to the same ability of goats and apes to induce the derision of humans. Christians further detested the pandering of jesters to the coin purses of their wealthy backers, arguing that being rewarded for buffoonery was an immoral way to live one’s life. Alain de Lille, for instance, criticized those: “who flatter to get out money, who slander to induce the rich to make generous offerings; who play the cither of adulation in the ears of powerful lords, who weigh praises according to the abundance of the table, who obtain by backbiting what they cannot obtain by virtue.”

They also rallied against dancing, believing it to be an instrument of the devil constructed to tempt men to the dark side. During the 13th century the Devil, Etienne de Bourbon insisted, was the creator of all dances. During a dance procession, leftward movement was a particularly disturbing sign of devilish machinations to Jacques de Vitry, who described dancing as a:“circle in the middle of which stands the devil, and where everybody goes leftwards, because everybody tends toward eternal death.”

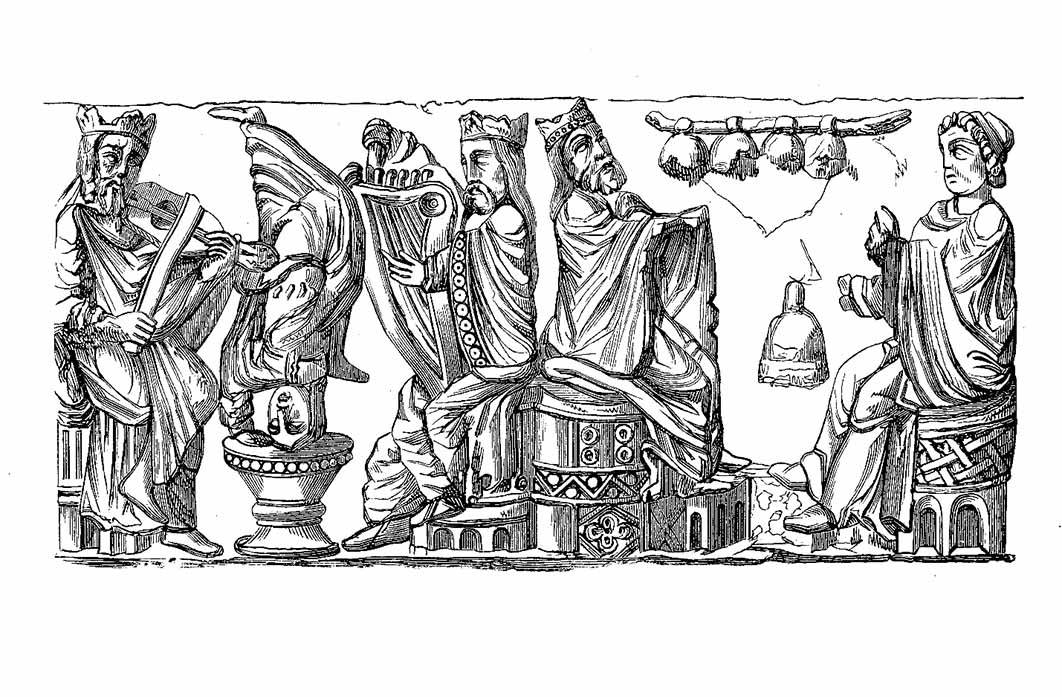

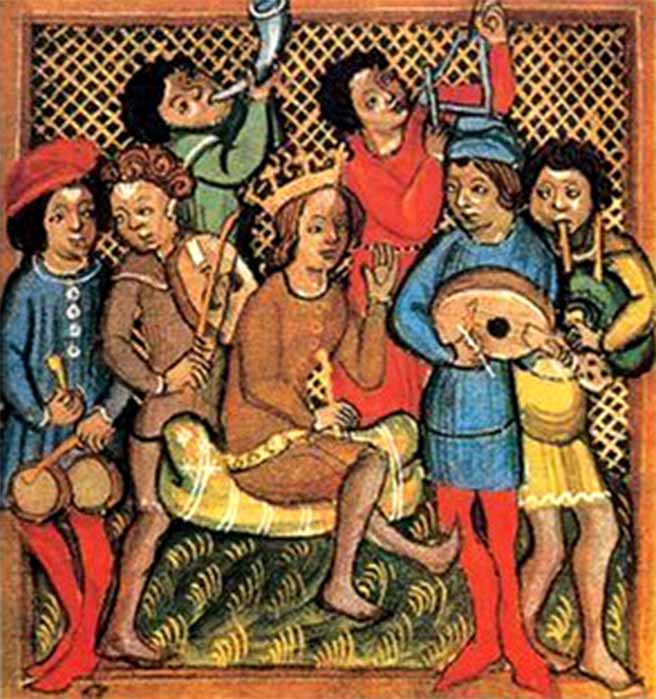

Medieval King John, his warriors, a hunter, ladies and the jester. (1216) (Archivist /Adobe Stock)

The marginalization of jesters was reflected in Gothic and Romanesque architecture, where sculptors and artisans had considerable freedom to choose iconographies. Many of them placed the jester figure in out of the way places, such as the cloisters or the stalls used by choir members, assimilating them into a netherworld of monsters and demons. Jester-monster hybrids were another feature of fine art, where physical deformities mirrored the perceived moral perversions of medieval entertainers.

However, from the 13th century, Christian writers softened a little, and began to recognize that jesters performed some useful moral functions. Thomas Chabham, an English sub-deacon, distinguished two types of jester. He castigated jesters who moved their bodies with “torpid gestures and dances” but praised those who sang about the heroic deeds of noble Christian knights and their transmission of Christian values into song.

Medieval musical performance: noble figures playing string instruments and bells, and a jester upside-down, bas-relief of 11th century (acrogame/ Adobe Stock)

Later in the 13th century, St Thomas would further rehabilitate the jester’s image, arguing that diversion was an essential part of human life and could be facilitated by their services, but only in moderation and at the correct time and place, and that jesters should be rightfully compensated for their efforts. By the 15th and 16th centuries, the demonization of jesters by Christian writers was subsiding, as views on the nature of folly in Christianity developed. Among the most important of these revisionist scholars was Erasmus von Rotterdam, who, in his Praise of Folly, lauded the virtues of the fool.

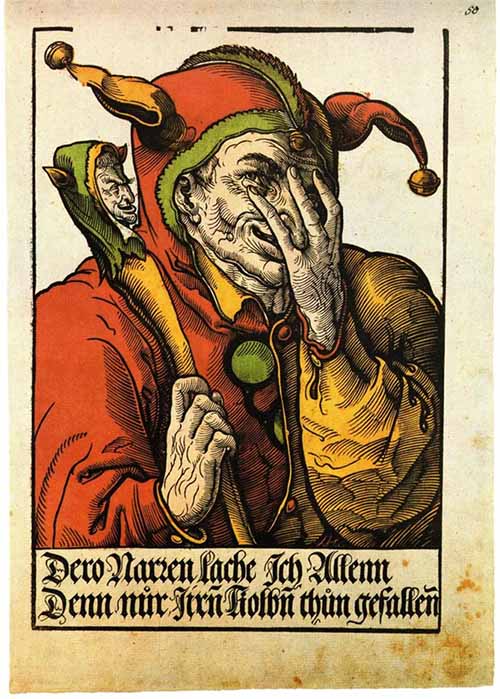

A jester shown with a marotte in a 1540 woodcut by Heinrich Vogtherr the Younger (Public Domain)

In the wake of the redemption of folly, the traditional colorful jester outfit, complete with baubles and the jester stick known as a marotte, appeared around the 14th century, as jesters started to become iconic and much-loved members of the royal courts.

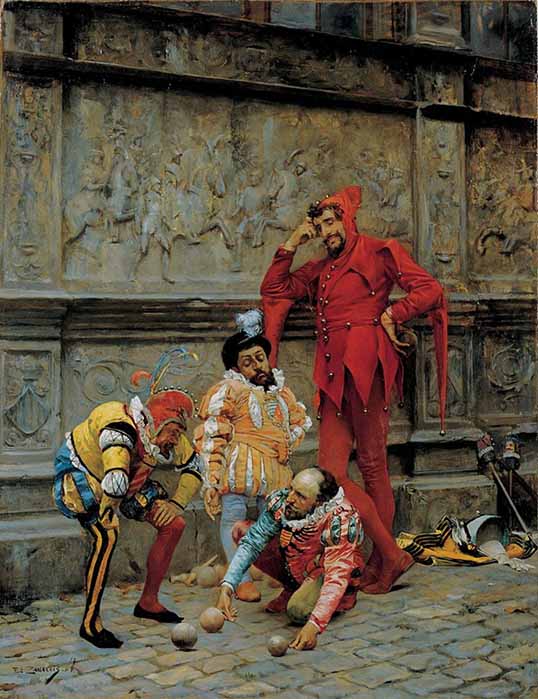

Court Jesters by Duardo Zamacois Y Zabala (1868) Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao (Public Domain)

Dwarf-Jesters

In the medieval epoch, the rich and powerful were obsessively curious about deformities, and often sought these qualities in their jesters. In fact, the earliest court jester on record, from the Ancient Egyptian Sixth Dynasty around 2300 BC, was a talented dwarf who gained the favor of the Pharaoh Neferkere: “Thou hast said in this thy letter that thou hast brought a dancing dwarf from the land of spirits… Come northward to the court immediately; thou shalt bring this dwarf with thee… for the dances of the god, to rejoice and gladden the heart of the king.”

- Semar: The Fallen God and Divine Jester of Indonesian Mythology

- The Jester of God and Murderous Heretic of 14th-Century Italy

- Elites and Gods: The Big Lives Of Dwarfs In Ancient Egypt!

Thus, from the earliest times, disability, and particularly dwarfism, was an esteemed characteristic of the jester, finding its fullest expression in the courts of medieval Europe. Sir Hudson, for instance, the cherished dwarf-jester of English Queen Henrietta Maria, who was often used as an errand-boy, earned a place alongside her in a portrait. James I of England’s prized jester, Archie Armstrong, was also a dwarf, described by a contemporary as “a yard high and a nayle, no more, his stature.” Treated almost like a pet, disabled jesters were often lavished with gifts from their adoring masters. In 1319, the French court accounts report the purchase of 32 pairs of shoes for “the Queen’s dwarf”.

Portrait of ‘Archibald Armstrong Archee the kinges Jester’ by Thomas Cecil. (1630) British Museum (Public Domain)

Dwarf-mania, on the other hand, had a darker side to it, and led to the development of the cruel practice of deliberately stunting the growth of children in order to sculpt artificial dwarves. Comprachios or ‘child-buyers’ from Italy and Spain made their living by kidnapping or buying children and deforming them. Dwarves could be produced by applying the grease of bats, moles, and mice to a baby’s spine and then prescribing them dwarf elder, knotgrass, daisy juice, and roots mixed with milk to further encourage the stunting of growth.

Las Meninas, depicting preoccupation with dwarfism by Diego Velázquez, from Prado (1656) (Public Domain)

The fixation with disability was almost a universal fetish, and was found in a wide array of societies outside of Europe. Aztec jesters, for instance, were almost always deformed, and were common denizens of Aztec chieftain Montezuma II’s court according to Spanish conquistadors. Legendary commander Bernal Diaz de Castillo, commented on this peculiar infatuation, noting how:

“Sometimes some little humpbacked dwarves would be present at his meals, whose bodies seemed to be almost broken in the middle. These were his jesters.”

In Turkey, under the Ottoman Emperor Suleiman the Magnificent, dwarves that were deaf and dumb were considered the most highly valued, as French traveller Tournefort chronicled:“And when a dwarf is found who was born deaf and is consequently mute, he is regarded like the phoenix of the palace, more admired then the most handsome man in the world, particularly if this ape is a eunuch.”

Dwarves were favored by rulers because their perceived imperfections allowed them to make jokes about the imperfections of the monarch. In addition, adopting a dwarf into the royal household was seen as an act of charity. By allowing a wretched creature completely outcast by society in, a noble could show themselves as compassionate leaders to the subjects and knights of his kingdom.

The Jester by Jacob Jordaens (1641-1645) Private Collection (Jl FilpoC / CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Hiring Process

The employment process of medieval court jesters was particularly striking for its informality and because it was one of the few jobs based on a meritocracy. The most common way a court jester could be employed was through happenstance and luck, as nobles on adventures beyond their ramparts were constantly on the look out for amusing people. If a person made a noble laugh, intentionally or even unintentionally, the there was a strong chance they could be whisked back to their castles.

Tarlton, the famous jester of Elizabeth’s court, was brought to her after a servant of the Earl of Leicester noticed his comical responses to questions: “Here he was in the field, keeping his Father’s Swine, when a servant of Robert of Leicester… was so highly pleased with his happy unhappy answers, that they brought him to court, where he became the most famous Jester to the Queen.”

Another, a dwarf jester called Nai Teh or ‘Mr Little', would become the most famous court jester of King Mongkut of Siam after his fortuitous discovery by one of the King’s relatives: “He was discovered by one of the King’s half-brothers on a hunting trip into the north and brought to Bangkok to be trained in athletic and gymnastic tricks. When he had learned these, he was presented to the king as a comedian and a buffoon.”

Sculpture of German Claus Narr at Torgau Schloss (Kolossos/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

Finally, one of Germany’s most recognized jesters, Claus Narr, was discovered by a German noble who was highly amused when Narr hurriedly tried to carry all of his fowls by securing the necks of his goslings through his belt and carrying the older geese under his arms, fearing they would be stolen. When his patron, Elector Ernst, saw Narr, he was sufficiently tickled, asking Narr’s father for permission to bring him back to his court, for which he enthusiastically accepted: “That would be great, Sir! I’d be relived of a great encumbrance thereby; the youth is no good to me - he makes nothing but trouble in my house and stirs up the whole village with his pranks."

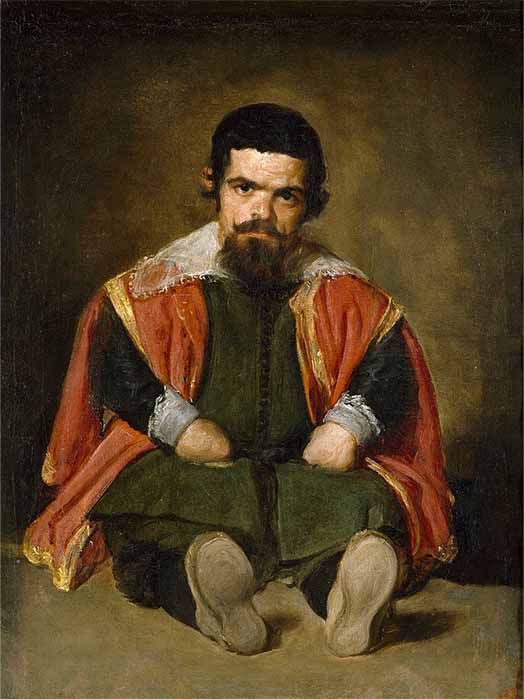

Sebastián de Morra court jester of King Phillip IV of Spain by Diego Velázquez (1645) Museo del Prado (Public Domain)

Unusual for typical medieval professions, jesters could come from a variety of backgrounds and were judged not on the greatness of their family or house but solely on how funny they were in true meritocratic fashion. In the same way that modern comedians start their careers on the local comedy circuits, this system was similar in medieval times, as a notably funny individual, perhaps performing in the street or doing something unintentional that amused a passing nobleman, could be chosen and promoted to the highest postings of the royal courts.

Another salient egalitarian attribute was that jesters were not discriminated against because of their gender, and several female jesters, who shared the same responsibilities and perks of their male counterparts, also found success in European manses. The most commended female jester, Mathurine the Fool, served in the courts of Henry III, Henry IV, and Louis XIII with distinction in the 17th century. In one episode she was able to exercise her sharp wit to a noblewoman, who complained she did not like having a fool on her right-hand side. Mathurine reportedly switched to the lady’s other side, quipping: “I don’t mind it either.”

Like Mathurine and many others, with a little luck, adequate comedic ability, and a preferred mental or physical handicap, a jester could suddenly find himself or herself launched into the halls of a royal palace, where life could become easy and carefree.

14th-century troubadours (Public Domain)

Jester-Musicians and Poets

Jesters were highly coveted as talented musicians, and often got their break if they could sufficiently impress with their musical aptitude. German jester Friedrich Taubmann, a lute player by trade, was said to have impressed a German bishop so much with his musical abilities that he was described as “the Second Orpheus.” With typical jester panache, Taubmann replied: “it must be true, since I also have a lot of Roman beasts around me.” Another funnyman, Italian violinist Petro Mira who visited the court of Anna Ivanova in Russia, turned a tender musical solo into a comedy routine, instantly impressing the Russian court who hired him as a jester, eventually giving him a tidy amount of money to retire.

Jesters of empress Anna Ivanova by V Jacobi (1872) (Public Domain)

Some jester-musicians were even entrusted as judges in musical competitions. Song Dynasty jester Immortal Revelation Ding assumed the judge’s mantle after he was chosen to decide whether a defunct musical mode should be used by Chinese musicians. Asked his opinion by the king, Ding’s reply was customarily acerbic with a hint of drama: “The jester walked slowly forward, turned to look at the seated throng, and said “Nice lyrics, shame about the tune!” The audience could not help but burst out laughing.”

As well as talented musicians, jesters were often expected to possess advanced knowledge of verse, poetry, and composition. The French court poet Andrelini, renowned for his hideousness, was chosen as the first ever poetus regius in Louis XII’s court. Similarly in India, Hindu jester Birbal became very close with Akbar the Great, who appointed him poet laureate owing to his renowned storytelling.

Medieval woman troubadour ( lynea /Adobe Stock)

In fact, magnates adored the jester’s ability to freestyle and extemporize. In Europe, a recurrent distraction for the king was to engage in the practice of verse capping, whereby the jester would respond rhythmically and playfully to a line from the monarch. Samuel Rowley’s 1604 play, When You See Me You Know Me, immortalized the interactions of Henry VIII with his favorite jester, William Somers. In one example, Henry starts with “the bud is spread, the Rose is red, the leafs is green”, and Somers responds: “A wench ’tis sed, was found in your bed, besides the Queene."

Jesters could adjudicate on the quality of prose as well as entering poetry competitions, often with a mocking touch. Esteemed Chinese poet Su Dongpo, for instance, keen to get Immortal Revelation’s view, showed his poem to the eminent jester and asked if it was better than the poems of his archrival, Liu Yong. Immortal Revelation deemed Su’s poems better, noting that it included generals, bronze, and lutes whereas Liu’s poems were just about a group of women singing. In an even less serious example, the Spanish jester Estebanillo Gonzalez, who served one of the most powerful leaders in Spain, the duke of Amalfi, purposeful submitted a nonsensical poem to the judges that won first prize. To him, it proved the point that if the poem was not understandable it would still be deemed as a good.

Jester Knight Christoph by Hans Wertinger (1515) Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid (Public Domain)

Jesters also exercised their musical and poetical expertise on the battlefield, and were expected to entertain their lord’s troops before battle to calm nerves. In 1066, William the Conqueror’s jester, Taillifer, sang songs about Charlemagne and Roland to psyche up William’s legions before the Battle of Hastings. Jesters were also useful for baiting the enemy troops, who could break their ranks in response to a jester’s insult, immediately giving the joker’s side an advantage. A jester’s time on the battlefield, however, could be fatal. Sometimes they were ordered to send messages to the enemy during a skirmish, but this could often end in disaster if the enemy disapproved, and a jester’s corpse or head could be catapulted back to his camp via trebuchet as a grisly response.

Advisors And Free-Speech Advocates

Court jesters were highly revered not only for their comedic and artistic exploits but also for their honesty. In a world where the king’s word was absolute, the court jester held the privileged position as the only person allowed to mock and even advise the king, within certain boundaries.

William Sommers would often poke fun at Henry VIII’s predilection for multiple wives, suggesting that he could choose a fool from their ranks: “… now you have had so many wives, and still living in hope to have more, why, of some of some of them, cannot you get a fool as he did? And so you shall be sure to have a fool of your own.”

Henry VIII and His Family (1545) - the man at the far right is the jester William Somers, and it has been suggested that the woman at the far left is the jester Jane Foole (Public Domain)

French jester Triboulet escaped death on a number of occasions thanks to his adept wit in his dealings with his master, King Louis XII and later Francis I. In one escapade, Triboulet found himself in hot water after mocking the Queen and being sentenced to death by the King. Upon asking by what method he would like to be executed, he would supposedly reply: “Good sire, for Saint Nitouche’s and Saint Pansard’s sake, patrons of insanity, I choose to die from old age.” This made the king burst out laughing, and the lucky jester was instead banished for his insouciance.

The behavior of the jester was often excused by kings who valued them as trusted confidants and allowed them to retain somewhat of an independent mind. In Norway, King Harald I always possessed a large retinue of skalds, a type of Scandinavian jester, with which he would discuss matters of empire: “He (Harald I) was hardly ever found among those who flattered and humored the king. In fact, it is characteristic of the skalds that they knew how to preserve their independence of opinion and maintain an attitude of frankness and self-possession which inspired respect.”

"Triboulet"; illustration for Le Roi s'amuse by J. A. Beaucé and Georges Rouget (1832) (Public Domain)

A jester’s very perceived ‘foolishness’ was seen an explanation for their tendency to speak in a truthful manner, and often hid behind it was a highly intelligent mind, as men often feigned idiocy for the privilege of having the king’s ear. This became such a problem in medieval Scotland that an Act for the Away-Putting of Feynet Fools was passed in 1449, handing out punishments such as amputation and ear-nailing for those who dared pretend to be a fool. French court jester Angeli was one of these ‘wise fools’, admitting to the Duchess of Orléans in 1710, who had a fear of fools, not to be scared: “Well, do not be afraid of me: I am not mad I just feign it.”

The wise fool, who deceived people into thinking he was less intelligent, was a facet of the widespread notion that jesters were also tricksters. Medieval tales of roguish individuals often mentioned their stint as a court jester, and the phrase ‘rogue-fool’ was a common term in German and Dutch parlance. Spanish fool Estabanillo Gonzalez, for instance, was also a capable cheater. On one occasion he received 25 ducats from a group of Jewish merchants and their lord, who took pity on him after he explained that the ashes in his hand were the only thing remaining of his father who had died during the Inquisition.

Nevertheless, kings and queens, usually surrounded by ‘yes men’, found the jester’s honesty refreshing, and under their aegis the jester’s opinions were often protected, making him a powerful advocate of free speech in a time when heretical ideas could have deadly consequences. French jester-poet Andrelini, for instance, was highly critical of theologians and was given a platform to attack them safely:

“(He) appears also to have enjoyed somewhat of the license and privilege of the jester, for he uttered bitter satires against the theologians at a time when to be attack them was to run the risk of death. And yet Andrelini shot his bolts with impunity.”

The Favourite of King Edward, Tom Le Fool by Eduardo Zamacois y Zabala (1865) (Public Domain)

Jesters who had adequately performed and become court favorites could be handsomely rewarded by their benefactors. King Henry II bestowed 30 acres of land to his jester, Roland le Pettour, on the condition that he return once a year to “leap, whistle, and fart” for the amusement of the regent and his entourage. King Edward I was similar enchanted with his jester, Tom le Fool, gifting him an enormous 50 shillings, a year’s salary for a commoner, for his excellent performance at the wedding of his daughter, Elizabeth.

Stańczyk was the court jester when Poland was at the height of its political, economic and cultural power during the era of the Renaissance, by Jan Matejko (1862) (Public Domain)

The Revival Of Theatre And The Jester’s Decline

The renaissance of the theatre in chose a more stable career on the stage instead of in the royal household where their security and even safety was so often reliant on the capricious whims of the ruler.

Samuel ‘Maggoty’ Johnson, a jester and playwright of the 18th century, represented this transitional stage, having one foot in both sides. Johnson worked for the Duke of Montague but also had a successful stage career with the help of his sponsor, who funded the writing of his play, Hurlothrumbo. The play was purportedly awful, with one reviewer stating: "A more curious or a more insane production has seldom issued from human pen.” However, it achieved considerable popularity, being shown at the Haymarket Theatre over 30 times.

Eventually, it was the jester, rather than the king, that had the last laugh, as multi-talented entertainers became affluent stars of society at the same time that the system of monarchism slowly crumbled. These ribald entertainers would eventually become the movie-stars and comedians of today’s society.

Jake Leigh-Howarth holds a masters degree in Modern History from the University of Leeds, where he specialized in the travelogues of Western visitors to Soviet Central Asia. His favorite historical periods include the Tamerlane Empire, the Mongolian Empire, and the Eleusinian Mysteries of Ancient Greece.

Top Image: The Court Jester by John Watson Nicol, (1895) (Public Domain)

References

Maitland, K. 2021. What was life like for a court jester?. History Extra. Available at: https://www.historyextra.com/period/medieval/what-was-life-like-for-a-court-jester/

Otto, B. 2001. Fools Are Everywhere: The Court Jester Around the World. University of Chicago Press.

Pietrini, S. Medieval Entertainers and the Memory of Ancient Theatre. Revue Internationale de Philosophie, 252:2.

Smallwood, K. 2019. What Was it Actually Like to be a Jester in Medieval Times?. Today I Found Out. Available at: http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2019/10/what-was-it-actually-like-to-be-a-court-jester-in-medieval-times/#google_vignette