Was Alexander the Great Entombed In Venice In Disguise As St Mark?

The Venetians themselves tell how in 828 AD two of their merchants, Tribunus and Rusticus, fetched a mummy from Alexandria in Egypt, which was said to contain the corpse of St Mark the Evangelist. This event they call the Translazione and it led their forefathers to found a church dedicated to St Mark, adjoining their Grand Canal, to accommodate the holy remains of the saint. This story is celebrated not only in their chronicles but is also illustrated in 12th-century mosaics in the church, now called the Basilica di San Marco. Furthermore, the same bodysnatching episode was independently recorded by Christian pilgrims who passed through Alexandria, Egypt more than a thousand years ago, not long after the event.

Venetian merchants with the help of two Greek monks take Mark the Evangelist's body to Venice, by Jacopo Tintoretto (1562) (Public Domain)

St Mark’s Tomb in Alexandria

Other surviving references in ancient texts allow the tomb of St Mark in Alexandria to be traced back in time to the end of the fourth century AD. St Jerome was the first to mention the entombment of St Mark in Alexandria in his De viris illustribus, written in Bethlehem in 392 AD. Palladius, in his Lausiac History, written in the early fifth century AD, describes a visit by Philoromus of Galatia to a Martyrion of St Mark in Alexandria in about the last decade of the fourth century AD. Later Adamnan in his book De locis sanctis, described a visit to a church and tomb of St Mark just inside the eastern gate of Alexandria by Arculfus in about 680 AD: “Approaching from the direction of Egypt as one enters the city of Alexandria on (almost) the north side a large church presents itself, in which Mark the Evangelist lies buried in the ground. His tomb is on view before the altar in the east end of this square church and a memorial to him has been built of marble stones on top of it.”

Earlier than this the investigation runs into problems. It used once to be thought that a Christian text called the Passion of St Peter incorporated a contemporaneous account of St Mark’s tomb in the early fourth century AD, but the relevant parts of this text are now recognized by scholars as fiction added in the sixth century AD. However, there are authentic earlier Christian accounts deriving from the third century (for example Dorotheus) and the fourth century AD (for example The Acts of St Mark), which specify that St Mark’s body was burned by the Pagans after they slew him in the first century AD. This widely attested cremation of the original corpse and a total absence of any record of St Mark’s tomb prior to the last decade of the fourth century AD make it doubtful whether the body stolen by the Venetians really was St Mark the Evangelist.

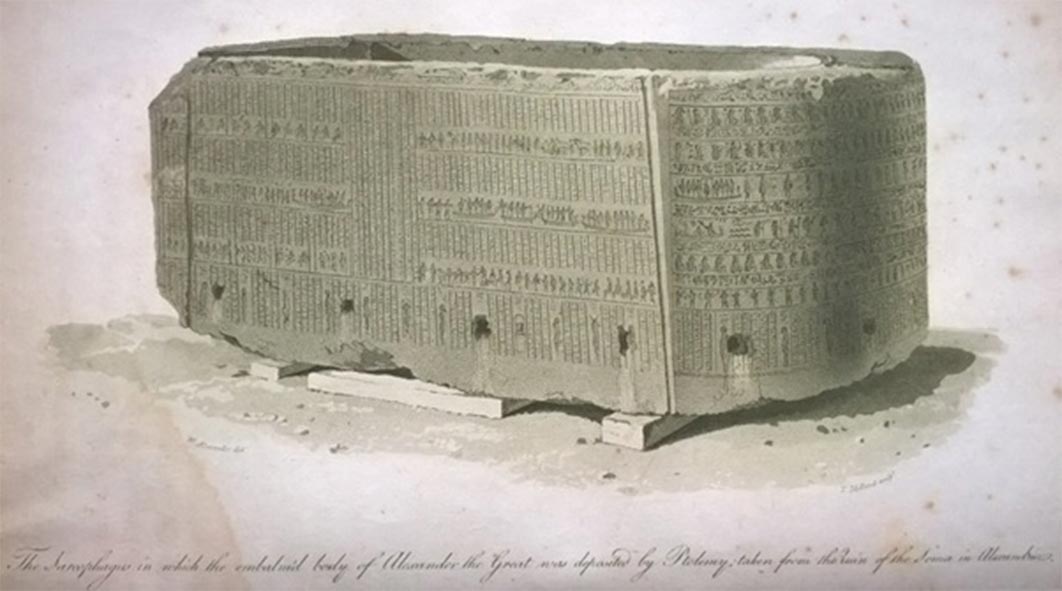

Engraving of the sarcophagus of Nectanebo II drawn by W. Alexander in 1805. (Image: Courtesy Andrew Michael Chugg.)

An Empty Sarcophagus

An empty sarcophagus found in Alexandria by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798 has an excellent claim to having been used to entomb Alexander, when he was first buried in Egypt by his general Ptolemy in 321-320 BC. The sarcophagus was taken to the British Museum when the British army defeated Napoleon’s troops in the Battle of Alexandria in 1801. The hieroglyphs and pharaonic cartouches with which it is covered clearly shows that it was made for the last native pharaoh of Egypt, Nectanebo II. But he could not have been buried in it, because he fled to Ethiopia in the face of a Persian invasion in about 341 BC, a decade before Alexander the Great captured Egypt and never returned. Therefore, it is virtually certain that this superb sarcophagus was available in an empty and pristine state when Ptolemy subsequently buried Alexander at Memphis, as attested by the Parian Marble, Pausanias, Curtius and Pseudo-Callisthenes.

- The Cold Case of Alexander the Great: Have Toxicologists Finally Explained His Untimely Death?

- Alexander the Great: The Economics of Upheaval – Part I

- Alexander the Great Destroyer? The Sacking of Persepolis and The Business of War – Part I

Alexander’s Tomb in Memphis

In 1988 Dorothy Thompson suggested in her book Memphis under the Ptolemies that the site of the tomb of Alexander was marked by the discovery of a semicircle of life-size statues of Greek philosophers and poets at the Memphite Serapeum in the Saqqara cemetery area. In 1955 Lauer & Picard dated these statues to the reign of Ptolemy. It is also significant that these statues guarded the entrance to a temple built by Nectanebo II and stood at the end of an avenue of 160 sphinxes carved under his grandfather Nectanebo I, the founder of the 30th Dynasty of pharaohs. The site of the Royal Cemetery of the 30th-Dynasty is unknown, but the Serapeum was virtually the most important temple in Egypt under these pharaohs, so its precinct is an excellent candidate for the location of their tombs. Furthermore, 30th-Dynasty tombs of nobles and courtiers lined the avenue of sphinxes at its Serapeum end and there was a mysterious windowless chamber about the correct size for the Nectanebo II sarcophagus that appears to have been tacked onto the side of the Nectanebo II temple and provided with a separate entrance.