Politics Behind The Jewish-Roman War: Vespasian Versus Izates Manu

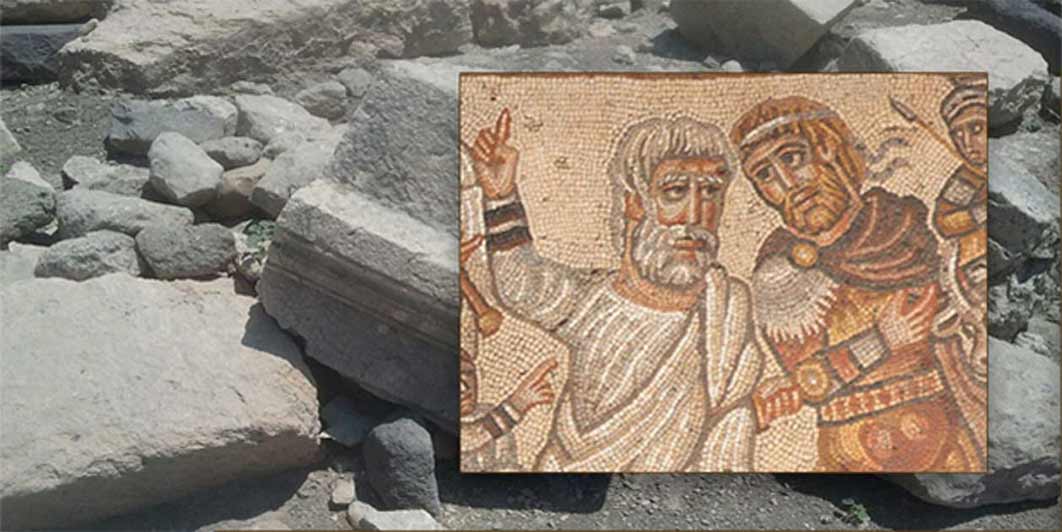

A few years ago, the world of biblical archaeology was treated to a spectacular mosaic find from the ancient Huqoq synagogue, an archaeological site just north of Tiberias. The image-exclusive was published by National Geographic, and it depicts a complex scene with a king and his army meeting with a group of people in white robes. Considering that most of the Huqoq mosaics depict scenes from the Tanakh, one might presume that the white robed characters represent the Jerusalem rabbis.

Architectural elements and ruins at the archaeological site of Huqoq, Israel (CC BY-SA 3.0). Inset, decorated mosaic floor uncovered in the buried ruins of a synagogue at Huqoq. (National Geographic)

Huqoq Mosaic: Who Is The King?

However, while most of the other mosaics were easily explainable in biblical terms, this particular mosaic remained a bit of a mystery. Who was this king, who met with the high priest of Jerusalem? The king is dressed in Roman-style armor and wears a diadema headband, denoting his royal status; and he is accompanied by soldiers, war elephants, and a calf. The bottom register of this mosaic shows that the army of this king had been defeated. So, who could this defeated king be? Professor Jodi Magness, the chief archaeologist at Huqoq, initially suggested it was Antiochus IV, who fought a battle with rebel Jewish forces in 167 BC, as detailed in the Book of Maccabees. The forces of Antiochus were indeed defeated. But for the 2016 National Geographic article, Professor Magness amended this identification to Alexander the Great, who did indeed meet with the Jerusalem priesthood on his way to Egypt, in 332 BC. But this was an odd identification, as Alexander the Great was never defeated by rebel Jews, as this mosaic strongly implies.

In addition, it is abundantly clear that both of these identifications are incorrect, because the king on the right wears a beard, leggings, and a Jewish payot or side-lock of hair. In great contrast, Alexander and Antiochus were always depicted as clean shaven, bare legged, and most certainly would not have worn a payot. Wearing leggings was a Parthian or Edessan custom, while Greeks and Romans were traditionally bare legged.

Father Abraham slaying his son Isaac, clearly wearing a payot (c 320 AD) (Public Domain)

Having excluded Alexander and Antiochus from this investigation, who can this monarch be? Could it be a fictional story? While this is possible, the other biblio-historical mosaics in this ancient synagogue would suggest not. The many mosaics at Huqoq seem to be instructional illustrations for the congregation, rather like the ‘stations of the cross’ illustrations depicted in many Christian churches. So what kind of biblical or historical lesson could a Jewish congregation learn from the Huqoq elephant mosaic?

Offering the Calf

The answer is to be found in the Talmud, where a character called bar Kamza presents a blemished calf from Emperor Nero to the Jerusalem priesthood, hoping it would be rejected in order to provoke the Jewish Revolt.

An extract from the Talmud reads: The destruction of Jerusalem came through a Kamza and a Bar Kamza in this way …. (Johannan) went and said to the Emperor, The Jews are rebelling against you. (Nero) said, How can I tell? He said to him: ‘Send them an offering and see whether they will offer it [on the altar].’ So (Johannan) sent (bar Kamza) with a fine calf (as an offering). While on the way (bar Kamza) made a blemish on its upper lip, or as some say on the white of its eye. The Rabbis were inclined to offer it in order not to offend the Government. But Rabbi Zechariah Abkulas said to them: ‘People will say that blemished animals are offered on the altar.’ They then proposed to kill bar Kamza so that he should not go and inform against them, but Rabbi Zechariah said to them: ‘Is one who makes a blemish on consecrated animals to be put to death?’ Rabbi Johannan thereupon remarked: ‘Through the scrupulousness of Rabbi Zechariah our House has been destroyed, our Temple burnt and we ourselves exiled from our land’. (Gittin 55 - 57)]