Kerameikos, Restoring Athens’ Necropolis To Life

From the ruins and rubble rises the narrative of the history of Kerameikos, restoring life to the Athenian necropolis. The obituaries on the gravestones and stelae and the sculptures on the marble sarcophagi monuments and naϊskos reflect people who mattered so much to their loved ones that their individual memories have been immortalized in stone.

Sacred Gate kouros (center) in Room 1 of the Kerameikos Archaeological Museum (

KatherineSoulis / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Development Of Kerameikos

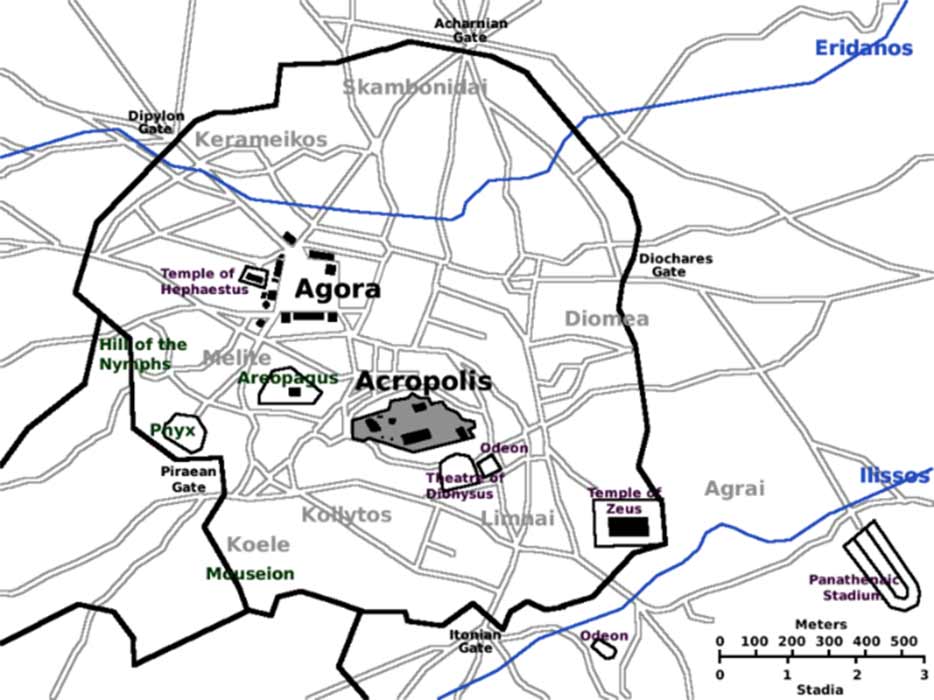

The Eridanos River valley bordering the north-west of ancient Athens, held the Deme of Kerameis, domain of the potters. According to mythology, Keramos was the son of the god Dionysus and Ariadne, the Minoan princess who had sailed with her lover the hero Theseus back to Athens after his defeat of the Minotaur at Knossos. However, Theseus abandoned her on the island of Naxos, where the god Dionysus had found her sleeping and wedded her. They had many children, of which Keramos was one – the etymology of the word ‘ceramics’ for pottery comes from Keramos. The Deme of Kerameis extended from the agora to the hill of the Pnyx and pottery workshops were later excavated up to the Academy of Plato.

Map of the Themistoklean Wall with Eridanos River flowing through Kerameikos (Public Domain)

Since the valley was initially a marshland, there was no ancient settlement, but people had buried their dead here since the Early Middle Helladic period at the beginning of the second millennium BC. By the end of the 12th century BC more people were buried on the north bank of the Eridanos, as more than a hundred Late Mycenean graves (1200 – 1100 BC) testify. These were simple cist graves, with no identification of the deceased, but they were accompanied by funerary artifacts such as amphorae. By 900 BC the cemetery had extended to the flat banks of the river. At this time bodies were cremated on a pyre outside the grave, and the ashes were transferred to an urn, which was buried inside the grave, covered with earth to form a tumulus. A simple stone stele marked the grave. The deceased of these graves were accompanied by richly geometric decorated ceramic grave offerings. This community may have formed the nucleus for the Deme of Kerameis to develop around the Eridanos River, which probably afforded the potters their clay for their wares.

10th century BC cinerary urn amphora ("Geometric period" pottery) of the Kerameikos Archaeological Museum (Giovanni Dall'Orto / Public Domain)

By the ninth to eight centuries BC burials as opposed to cremations became popular again and stelae were replaced by vase grave markers. Geometric motifs made way for depictions of people and animals, representing funeral ceremonies such as chariot races, to commemorate the dead. Even mythology motifs now decorated the vases. Clearly a more affluent community, with trade links to other cities and the East was emerging. By the seventh century BC the cemetery had expanded to the south bank. Graves were marked by stelae and stone memorials. The large solitary tumulus on the north bank belonged to a powerful aristocratic clan, illustrating the social and economic differences between the aristocrats and the common citizens, that led to the Draconian laws in 621 BC. By 590 BC Solon had set a limit on the cost of a funeral to curb the extravagance of the aristocrats. By the mid-sixth century BC Kerameikos had become Athens’ official cemetery.