Ancient And Modern Cannibalism: A Question Of Taste

Of all the horrible and shocking things that human beings can do to one another, nothing alarms, disgusts, terrifies – or fascinates – more than cannibalism. The subject is intriguing, in part, because of its complexity. What causes people to eat other people? Researchers have divided cannibalism into at least nine categories, with some of the main types being survival, aggression, and ritual. Survival cannibalism involves both necrophagy - eating the dead so as not to waste the calories - and killing others to make it through famines. Aggressive cannibalism is more about hunting and eating one’s own species because it is easy, or some humans have simply developed a taste for it. Ritual cannibalism is complicated, and in many cases, it is related to religion. Much of it, however, centers around honoring loved ones or keeping their essence nearby. Other ritual cannibalism stems from wanting to assume the strength, courage, or other desired aspects of a fallen enemy.

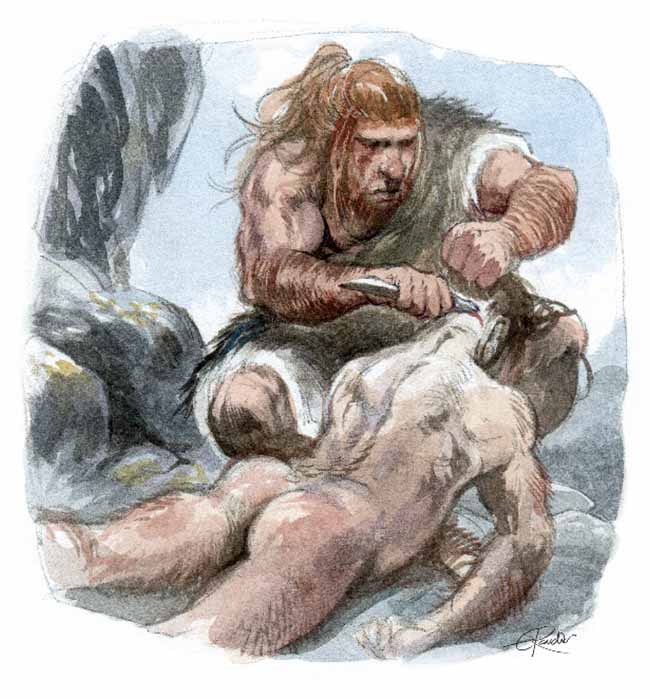

Prehistoric cannibalism by © Emmanuel Roudier (2008) Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies. (Permission granted to Dr N Bockoven)

Were Neanderthals Cannibals?

Were Neanderthals really cannibals? The short answer is yes, a fair percentage of them were. The renowned paleogeneticist and recent Nobel Prize winner, Svante Pääbo, states that human bones with cut marks or percussion breakage to extract marrow are "typical of many, even most, sites where Neanderthal bones are found." Pääbo is the man responsible for sequencing the first full genome of a Neanderthal in 2010. That same year, he sequenced the genome of a human the world knew nothing about, and he thereby introduced the Denisovans.

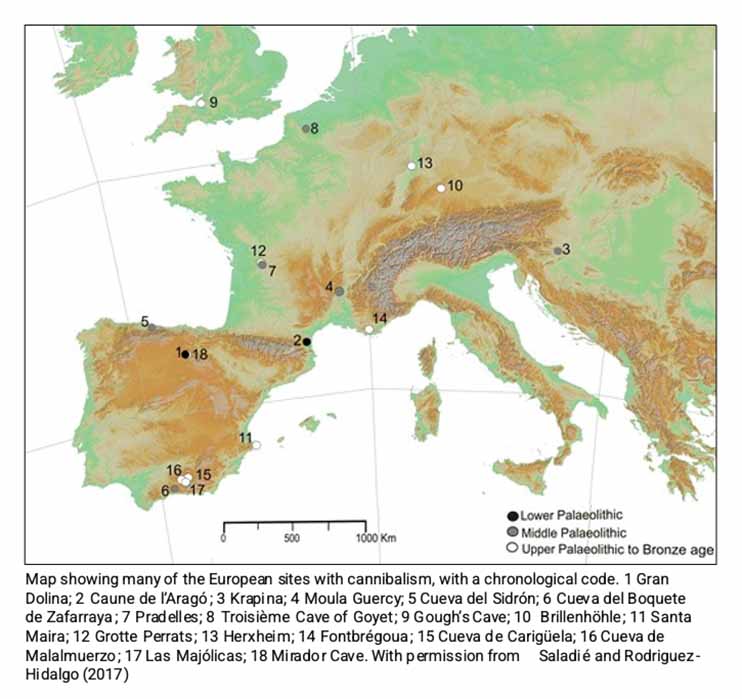

Neanderthals certainly were not alone in their cannibalism. Homo sapiens have their own rich history of it. Strong evidence of Paleolithic to Bronze Age cannibalism has been found in at least 18 widely dispersed archaeological sites in Europe. Lower and Middle Paleolithic (Neanderthal and older) cannibalism accounts for about half of these, including Goyet, Belgium, Gran Dolina and El Sidrón in Spain, Moula-Guercy, Combe-Grenal, Caune de l'Arago, and Les Pradelles in France, and Vindija and Krapina in Croatia. Several other sites have probable cannibalism. Krapina is the site with the largest collection of separate Neanderthal remains, and most researchers agree that portions of more than 80 individuals have been found there. The bones indicate that Neanderthals, to paraphrase philosopher Thomas Hobbes, lived lives that were nasty, brutish, and short. The typical age at death was between 14 and 24 years. Most of the remains show evidence of periodic malnutrition, famine, and/or disease. Many of the individuals had been butchered, cooked, and eaten.

When human remains found at an archaeological site such as Krapina are consistent with a nutritionally motivated fragmentation, that is, when patterns of cut marks, scorching, percussion breakage, and other fractures match what is seen on non-human faunal remains, the assemblage is usually categorized as evidence of cannibalism. For instance, cut marks on Neanderthal bones at Goyet Cave in Belgium are virtually identical to those found on prey animals which have been processed for meat. The percentage of human remains receiving such treatment is also important. At the Goyet site, as well as at Boquete de Zafarraya and El Sidrón in Spain, and Les Pradelles, and Moula-Guercy in France, the exploitation of human remains was intensive, with more than 30 percent showing such processing. The evidence of such thorough carcass processing (skinning, evisceration, disarticulation, and defleshing) inferred from the cut marks and bone locations strongly suggests the pursuit of calories as opposed to ritual cannibalism where consumption is more typically restricted to select parts having a definite cultural value, for instance the heart for bravery.

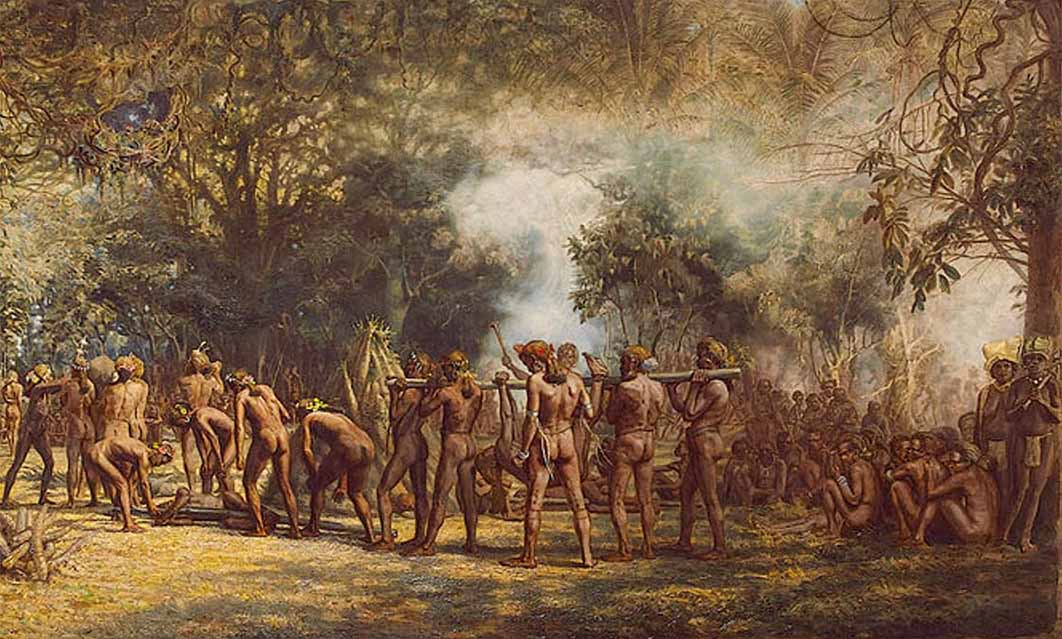

Cannibals preparing their Victims by Francisco de Goya: (1808) (Public Domain)

The Clan at El Sidrón Cave, Spain

Perhaps the saddest case is that of the Neanderthal remains recently found at El Sidrón Cave in Spain. There, about 49,000 years ago, 13 members of a clan, including men, women, and children, were eaten. The bones indicate intense nutritional stress from a diet of moss and mushrooms. The overall evidence including cranial trauma, has convinced many researchers that the cannibalism was aggressive, by another group for survival or predation, not just one group eating its own dead. Life does not get much worse than that - starving on moss and mushrooms, then being killed and eaten by neighbors. Nasty, brutish and short. The El Sidrón bones also feature at least 17 birth defects, probably the result of inbreeding. This indicates low population densities for Neanderthals of that time, or at least low social cohesion. One can speculate that the risk of cannibalism may have been widely recognized, leading to distrust and xenophobia of any people outside the clan or kinship band. That would make groups more insular, and serve to heighten the chances for inbreeding.