Plain Sailing: Shapes And Speed In Historic Naval Designs

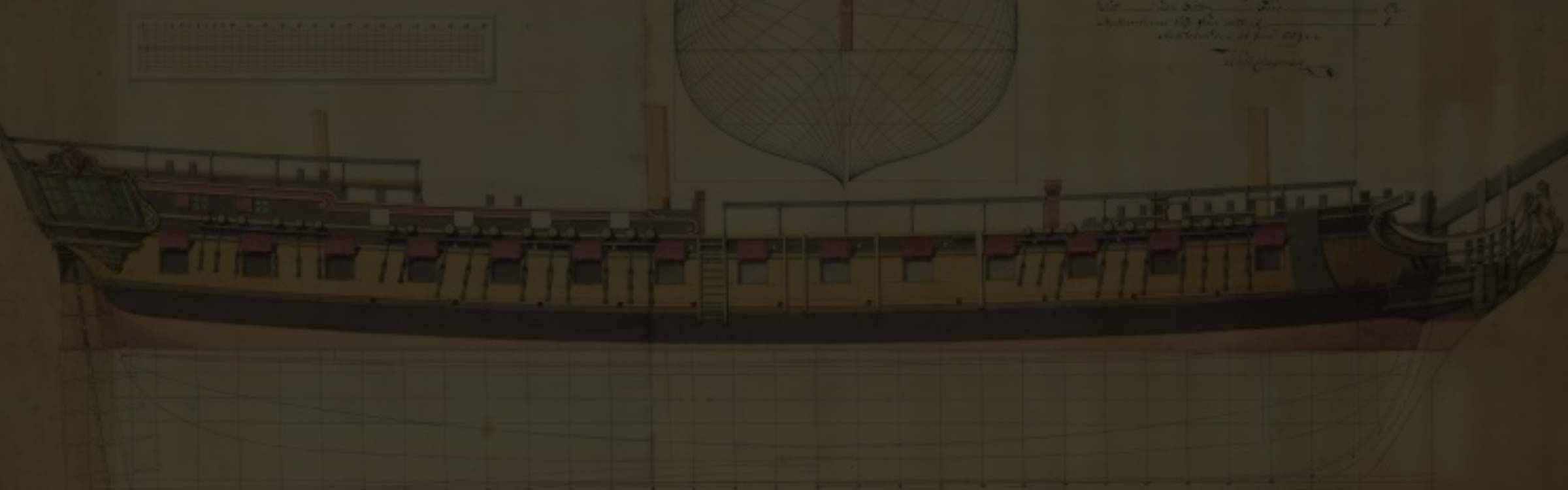

During the 1700s, European naval studies were decisive and very important, so much so that espionage by Spain and France against England for military and naval purposes alone had become a real scourge. The designers of the time had succeeded in improving vessel stability, hull, tonnage, and many other features as never before. What had not yielded the desired results, was the refinement of shapes. The perfect combination of a vessel’s shape and increased speed was still a vital missing element of shipbuilding. There were many reasons for this, starting with the initial constraints of each design aimed at a specific use and the difficulties of adequate measurements, even in shipyards.

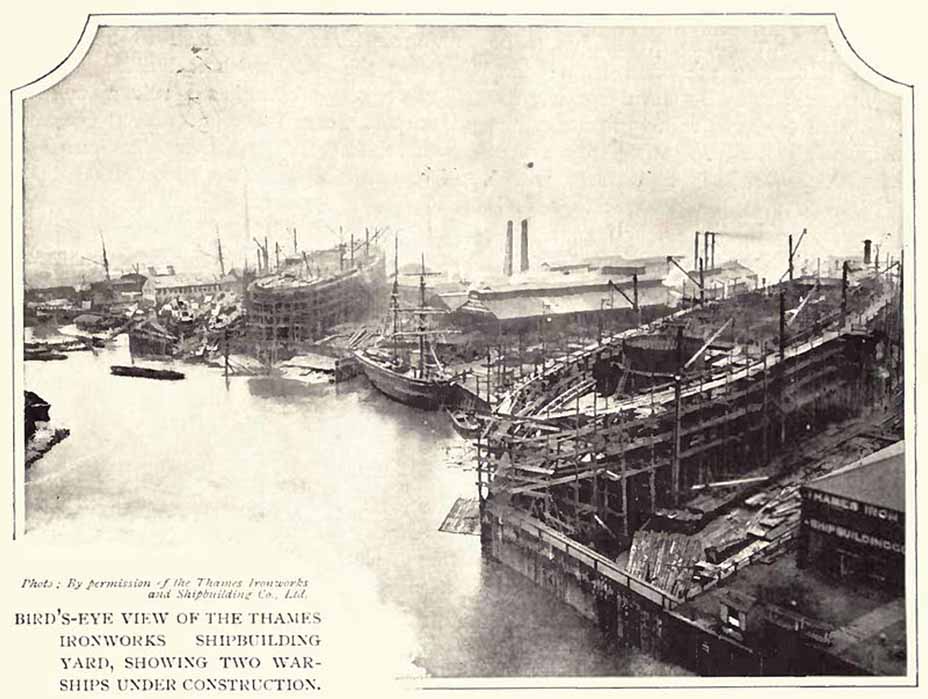

Two warships being constructed at the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company. (Public Domain)

Constraints of Balance

In the naval military, it was the artilleries and their placement on board that were the most important constraint. Guns weigh a lot and require crew personnel in adequate numbers to operate them properly. In addition, the displacement parameter was a requirement that radically differentiated military ships from those for civilian use. In the merchant marine field, on the other hand, it was the internal volumes, rather than the guns, that were a constraint, since a greater volume of cargo loaded meant a greater cash profit for the company.

A carronade, a short squat cannon from the former Carron Works in Britain (Kim Traynor/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Americans were much more focused on the pursuit of speed than their British cousins, and this is also noted in the history of the development of fast sailing ships. Chapelle, an American historian, defined this as an American characteristic devoted to pragmatism; moreover, greater speed meant greater excellence in American seamanship. Curiously, even today if one wants to study naval architecture of the 1700s, even the Americans have to resort to British archives.

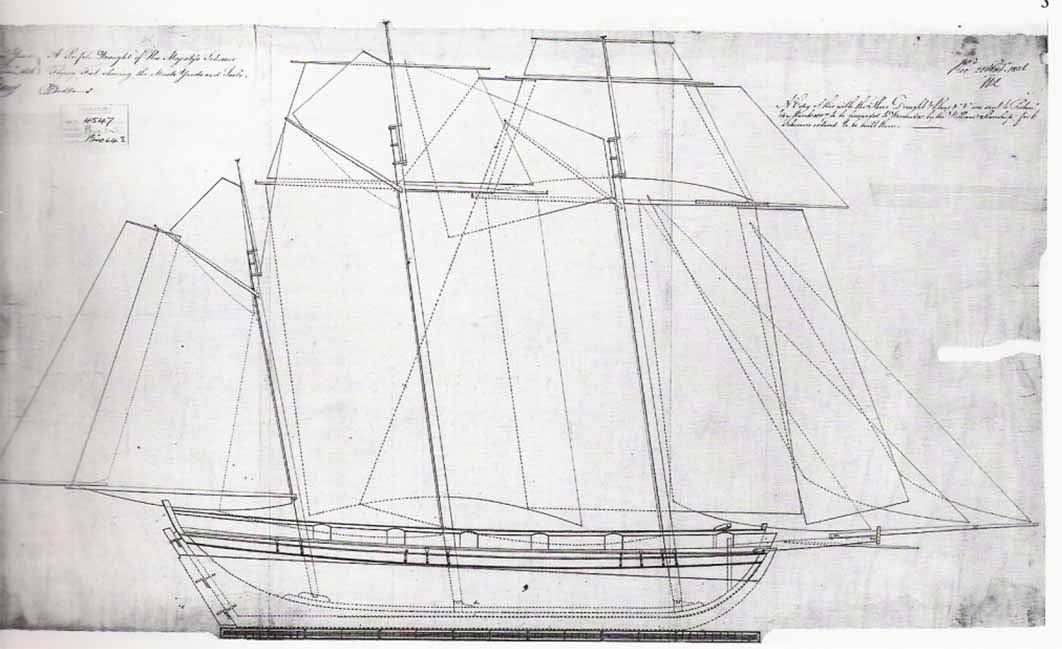

In old Europe only the smaller ship categories could more freely allow designers to use the speed parameter in their designs as they pleased, without constraint. These ships certainly included those devoted to postal service, coastguards (such as brigs and schooners) and ships used for illicit activities, such as smuggling or even piracy. Of course, privateers carried signed and authorized letters of marque and their vessels were financed by nobles who intended to profit from certain areas or certain geopolitical vicissitudes. Of course, this type of activity differed from piracy (punishable by death) only and exclusively from the letter of marque.

Drawing for the Flying Fish class, modelled on an American Baltimore clipper, sent to Bermudian builders by the British Admiralty (Public Domain)