True Democracy? Oligarchy Versus Ochlokratia In Athens

If what is taken to matter most is the power of decision-making, and, as part of that, the power to call executive office-holders to account by judicial or other means, then the first democracy properly so called anywhere in the world was that of Athens, brought it into being in stages during the approximately half-century between circa 508 and 462 BC. Aristotle in his Politics treatise of circa 330 BC, refers to some 1,000 separate political entities in Hellas (the Greek world) between about 500 and 300 BC of those, perhaps a quarter, perhaps as many as half at one time or another within those two centuries experienced some form of democracy.

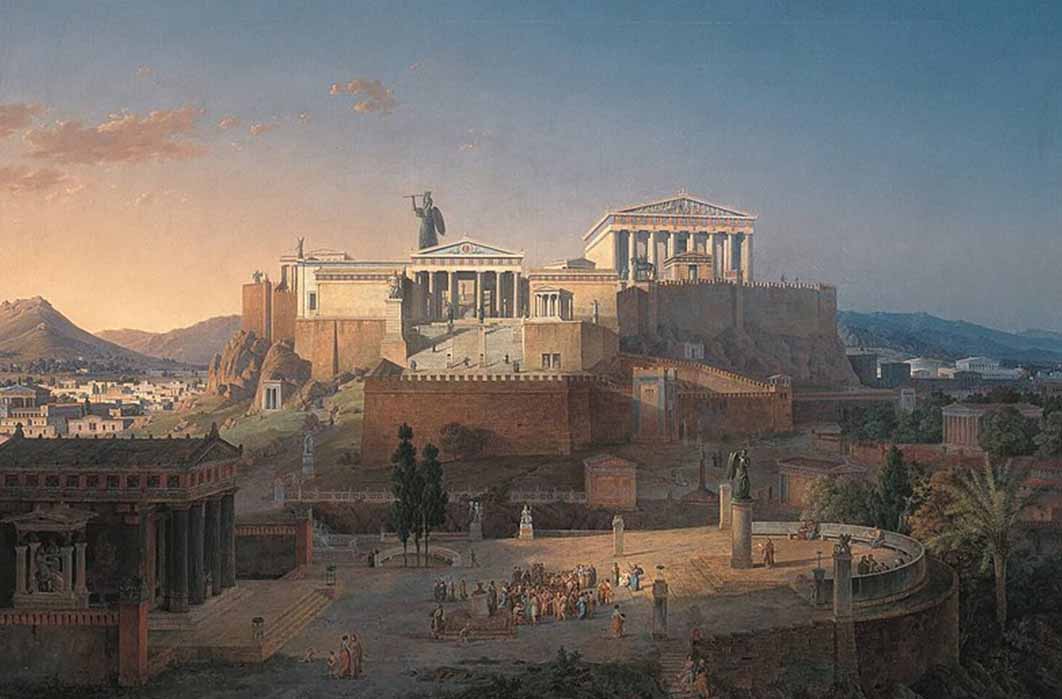

The relief representation depicts the personified Demos being crowned by Democracy (276 BC) Ancient Agora Museum (Jerónimo Roure Pérez/ CC BY-SA 4.0)

Etymologically, the ancient Greek coinage dêmokratia, first attested in 425 BC, combined dêmos and kratos. The meaning of kratos is unambiguous: power or might. The meaning of dêmos, however, is ambiguous: either ‘people’ - the people as a whole, the city or state, for example of Athens - or the majority of the empowered (adult male citizen) people. So, ancient Greek dêmokratia could mean either ‘the power of the people’ (as in Lincoln’s ‘government of the people by the people for the people’) or the power of the masses, over both the organs of state governance and over the Elite Few citizens. Members of the Elite Few rich citizens, might well have preferred oligarchy (rule of the Elite Few) to democracy, which they viewed as merely mobocracy or mob-rule.

Athens - Ripe for Democracy

Preconditions of the origins of democracy at Athens include: the invention of the polis or city-state around 700 BC; a rule-bound political entity based on a definition of the privileges and duties of citizens (always free adult males); weakening of the original rule over the poleis by exclusive noblest and affluent aristocracies, through such factors as intermarriage between noble and non-noble families, the impoverishment of some aristocrats, and the rise of new-wealthy families due to for example success in overseas trade; the shift from long-range fighting conducted only by the most wealthy to the dominant role of infantry phalanx fighting undertaken by more middling-rich heavy-armed soldiers; and the emergence in some of the larger, more important poleis (Athens was one) of sole-ruler autocrats called ‘tyrants’ who found it helpful to dispossess or weaken the older ruling families by spreading political power more widely down to poorer, commoner citizens.

- The Ins and Outs and 'Idiots' of Greek Democracy

- Athens, Home of Democracy: From Antiquity to Modernity

- How Ancient Greeks Kept Ruthless Narcissists from Capturing their Democracy

Religion was never seen as a distinct sphere, separate from a secular sphere, so democratic politics was always heavily invested in and inflected by religion. Yet the Greeks had no single word for ‘religion’, but used periphrases such as ‘the things of the gods’ - ‘gods’ being understood as a plural, polytheistic, term embracing both gods and goddesses. The overriding goal of human relations with the divine pantheon was to keep the most relevant gods and goddesses happy, to maintain the ‘peace’ of the gods, by duly ‘acknowledging’ them through animal blood-sacrifices, prayers and festivals.

Athen’s fleet conquers the Persians at the Battle of Salamis, after the Pythia of Delphi advised a “wall of wood,” by Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1868) Maximilianeum, Batavia (Public Domain)

The democratic Athenians between them devoted more days of the year to festivals of the various divinities than did any other Greek city. All such Athenian festivals, whether national or local, were managed democratically. Likewise, all matters of religion, including oracles. There were many Greek oracular shrines scattered throughout the Greek world (in Asia and Africa as well as Europe), but the most famous was that of Apollo at Delphi in central mainland Greece. Consultations here, both personal and state, began in the eighth century BC. One of the most famous episodes of Athenian official state consultation of the Delphic Oracle occurred under the democracy in the 480s BC in anxious preparation to face a massive impending invasion by the empire of Persia. The Delphic priestess gave conflicting responses to different consultations, so that it fell to the Assembly of the Athenians to decide which interpretation to favor and act upon. Happily, they chose correctly, built a large fleet of trireme warships, (‘a wall of wood’) and Athens emerged victorious from the Persian Wars – and with its still evolving democracy intact.

Around 600 BC there emerged a tendency for a very small elite group of Greek intellectuals on both sides of the Aegean Sea to question the inherited religious worldview in favor of a more scientific, mechanistic understanding of the cosmos, how it came into being, and what it was composed of. But it took a very long time before the role of gods and goddesses in making and determining the nature of the world was at all seriously challenged by any large number of citizens. The earliest thoroughgoing Greek atheists are not attested until towards the end of the fifth century BC, well after the introduction of democratic systems of government.