Challenges of Infant Mortality in Ancient Egypt: Amulets, Spells and the Divine—Part II

Among all the perils that the ancient Egyptians battled through their use of religion and magic, none came close to the poignant and desperate prayers they made to save the lives of their offspring. In a time when the lack of proper medication and the understanding of how and why diseases struck existed; the people did the very best they could by beseeching the pantheon of gods and goddesses for help. Magical amulets, wands and spells were the most sought-after means of protecting children and their mothers against the influence of malignant forces. So successful were some spells to combat infant deaths, for instance, that they were passed down faithfully through word of mouth from generation to generation.

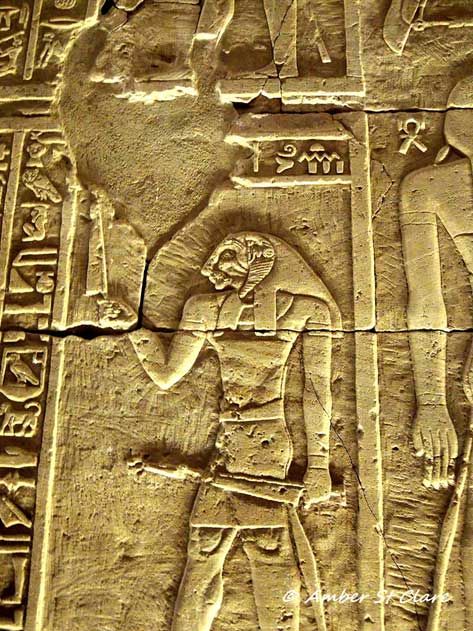

Mother Love: Detail from a relief shows Pharaoh Seti I as a child sitting on the lap of goddess Isis. Her right arm is resting on his back while she gently caresses his face with her left hand. This scene can be found on the western wall of the Second Hypostyle Hall. Temple of Seti I, Abydos.

Child Protectors Here and Beyond

Egypt’s geography and weather made it an appealing place for venomous reptiles and insects such as snakes and scorpions. Since Heka encompassed magic, healing and the practice of medicine; magicians called Sau supplied charms to ward off the ill effects of bites and protect the wearer from harm. Even water poured over certain idols or statues - such as the idol of ‘Horus the Child’ - whilst prayers were recited was considered ‘holy’ and was said to have medicinal and healing properties. Death, disease and plagues were thought to be an act of a vengeful, angry deity. So, every method was employed to supplicate and placate the gods.

The central scene of the Metternich Stela (Horus-stele or ‘cippus’ stone slabs) shows the figure of the child Horus, or Harpocrates, associated with the newborn sun, with the head of the god Bes above him. He stands on two crocodiles and holds dangerous animals (snakes, scorpion, lion, and antelopes), demonstrating that with supernatural powers even a child can overcome dangers. The inscriptions are a set of 13 spells against poison and illness. These were designed to be said by a physician treating a patient, but their effectiveness could also be absorbed by drinking water that had been poured over the stele. Reign of Nectanebo II. Thirtieth Dynasty. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In many ways, magic was a sustainer of life, in that it provided an escape route; or better still, a comforting answer when beset by calamity. While a religious approach to a woman who’d lost her child could be ‘no one can fight destiny’ – magic gave answers or the means to understand why a negative situation occurred and how to overcome or make peace with it. “Of all the powers that could be set against demons and the bau of deities: Taweret the female hippopotamus and the lion-dwarf, Bes seem to have been the most popular. Both were particularly associated with helping humans through the great crisis of birth. By the first millennium BC, Bes was thought of as a life-force. He was equated with Shu, god of the air, who filled the cosmos with the breath of life. This pantheistic form of Bes absorbed the protective attributes of many other deities,” writes Geraldine Pinch. Beset, the female counterpart and wife of Bes, was believed to protect her devotees against ill; and aid in sexual pleasure and childbirth. She was also a goddess of the harvest and a divine nurse.

- Excavations in village reveal sad fact of high medieval infant mortalities

- Two infant graves dating back 11,500 years found in Alaska

- Analysis of Viking burial site reveals the harshness of life in early Christian Iceland

The vast Egyptian pantheon included many deities and divine beings who were mainly invoked for the purposes of defensive magic. During Graeco-Roman times, a lesser-known deity called Tutu, the son of the powerful creator goddess Neith, was worshipped at Sais. He combined the attributes of a sphinx and a griffin; with a human head, the body of a lion, the wings of a bird, and a snake for a tail. Primarily, Tutu was identified with the epithet ‘the one who keeps enemies at a distance’. This was in keeping with his monstrous power that could be used to defend humans from demons or hostile manifestations of other deities.