Killer Queen: Meet Queen Elfrida – The Original Wicked Stepmother

History has seen some incredible, cut-throat politics and lurid scandals, including the reign of Queen Elgiva: a teenage Saxon princess who was caught enjoying a threesome (along with her mother!), in the bed of King Eadwig, on the day of his coronation and at a time when he should have been discussing affairs of state with his noblemen and courtiers.

Elgiva faded from the pages of history just four years later when King Eadwig conveniently died (he was probably murdered) and was replaced by his brother Edgar.

King Eadwig (Public Domain)

Known as King Edgar the Peaceable (or Peaceful), he went on to rule for 20 years and, according to one historian, enjoyed a reign “singularly devoid of recorded incident.” This is not exactly true, as according to legend there was one very dark secret in Edgar’s life that was to have disastrous consequences for the Kingdom of England!

Eadwig’s brother, Edgar became King (Public Domain)

The King’s Dark Secret

Edgar, in common with most Saxon kings of this era, practiced what we’d now call “serial monogamy.” Kings would only have one wife or mistress/concubine at a time, but they would be discarded – the consanguinity rules (viz that they were too closely related) were a popular way of ending no longer convenient marriages – and sent to a nunnery when the monarch took a fancy to another woman.

So, for example, Edgar had a relationship with a woman called Aethelflaed (Ethel) by whom he had a son Eadweard (Edward). Then he had a relationship with Wulfthryth (Wifrida) by whom he had a daughter Eadgyth (Edith). And then along came Aelfthryth (Elfrida) by whom he had two more sons: Edmund, who died while still an infant, and Aethelraed (Ethelred).

Edgar’s dark secret relates to how he first met and wooed Elfrida. The king had heard that an ealdorman (earl) called Ordgar, in what is now Devon, had a beautiful daughter whose mother was a member of the royal family of Wessex. As he was looking for a queen, Edgar commissioned an East Anglian thegn (thane/nobleman) called Aethelwold to visit her and offer her a royal marriage—if she really was as beautiful as everyone said.

She was as beautiful as everyone said but, concealing his true mission from both her and her parents, Aethelwold wooed and married the girl himself, reporting back to Edgar that Elfrida was a “vulgar and common-looking” and “unworthy of a royal marriage”.

Double-Cross

Initially Edgar accepted this explanation, but as he continued to hear reports of her beauty, he decided to visit the happy couple himself. News of the pending royal visit threw Aethelwold into a panic and, while begging Elfrida to make herself as unattractive as possible and wear her plainest clothes, he inadvertently revealed how he had deceived both her and the king.

- The Wicked Queen and Her Scandalous Daughter: How Murder & Mayhem Took a Saxon Princess from Palace to Poverty

- Putting the Sex Back in Wessex: The Scandalous Reign of Queen Elgiva & Her Clash with a Demon-Fighting Bishop

- Witch of Eye Burned Alive at the Stake: Did She Use Black Magic to Bewitch a King in a Game of Thrones-Style Plot?

As all contemporary reports suggest Elfrida was an ambitious woman, the realization she had missed out on becoming queen did not go down at all well. Repaying Aethelwold’s deceit in kind, she agreed to appear dowdy, but she actually went in the opposite direction and was presented to the king wearing the Anglo-Saxon equivalent of hair extensions, spray tan, and a gown that showed plenty of cleavage and was split to the thigh.

It was lust at first sight and the couple quickly came to an understanding they would marry, regardless of the fact Elfrida already had a husband and King Edgar had a wife. This issued was resolved when, shortly after their meeting, Aethelwold was invited to go on a royal hunting expedition and Edgar accidentally speared him with a javelin and killed him. As we will see in a later, royal hunting expeditions could also be conveniently lethal.

Edgar the Peaceful (Public Domain)

Soon afterward, Edgar divorced his wife Wilfrida on the grounds of consanguinity and married Elfrida. A few years later still, during the elaborate coronation ceremony (it was actually a second coronation for Edgar) Elfrida was anointed with holy oil and crowned queen, giving her a higher status than almost all the Wessex queens of that era.

And then they all lived happily ever after… except they didn’t, as Edgar unexpectedly died in 975 (of natural causes) just a couple of years after his coronation and while he was still in his early thirties.

A Game of Thrones

Edgar’s death immediately prompted a succession crisis between his two surviving sons. Edward was the oldest; he was a young teenager of about 12 or 13 years, but there were doubts over his legitimacy, while Ethelred was legitimate but just nine years old.

A further complication was the royal court was split, almost to the point of breaking out into a civil war, between nobles who supported the late King Edgar’s religious policy, which included generous grants of land and properties to the Benedictine abbeys, and the anti-monastic reactionaries who wanted to reverse these policies, so they could claim or (in the case of those nobles who had been dispossessed by the grants) reclaim the religious estates for themselves.

Not surprisingly, the ambitious Dowager Queen Elfrida was a vociferous supporter of her own son’s claim to the throne. But the pro-Edward camp, championed by the influential Archbishop Dunstan, was victorious and Edward took the throne.

However, then came that fateful day in March 978 when the young king was out hunting and, late in the afternoon, visited Queen Elfrida at her home at what would later become Corfe Castle in Dorset.

Edward is offered a cup of mead by Elfrida, wife of Edgar, unaware of nefarious intentions. (Public Domain)

While still mounted on his horse, King Edward accepted a welcoming flagon of mead from Elfrida’s own hands but then, as he was drinking from the cup (and, according to one version, while “allured by her female blandishments” – she would still have only been 33 at the time) her attendants and retainers fatally stabbed him in the back with their daggers.

Elfrida puts her plan of murdering Edward into motion. (Public Domain)

Murder!

There are various theories explaining the murder and all raise as many questions as they seek to answer:

- Were the murderers in Ethelred’s service seeking to place their master on the throne?

- Were the murderers acting on behalf of a member of the Wessex nobility who was concerned the king was becoming too independently minded?

- Was the murder motivated by a personal quarrel with Edward who, according to many accounts, did have a mean and spiteful temper?

- Was the murder part of a plot personally devised by Elfrida to propel her son to the throne, as was suggested by the chronicler John of Worcester?

- Did Elfrida herself actually plunge a knife into King Edward, as the chronicler Henry of Huntingdon later (over a century later, as it happens) wrote?

- And, even if she didn’t actively participate in the murder, is Elfrida still implicated in the regicide for allowing the killers to go free and unpunished?

Whatever the actual cause, the effect was the same: a change of monarch with Ethelred being crowned a fortnight later on 31 March, although because of his youth (he was only 12 at the time of his coronation) his mother Queen Elfrida ruled as regent for the next six years!

One of the few things we can be certain of is Ethelred not only had no involvement in the murder of Edward but was also unaware of any plots. In fact, in a story reminiscent of the incident in the book “Mommie Dearest” (about the actress Joan Crawford traumatizing her daughter by beating her with a wire coat-hanger), it is claimed Queen Elfrida beat Ethelred with a candlestick on seeing him mourn for the half-brother who had blocked his path to the throne. The memory of this beating apparently stayed with Ethelred for the rest of his life, giving him a terror of candlelight.

The Prophecy

Ethelred’s coronation was the last state event in which Archbishop Dunstan took part. When the young king took the usual oath to govern well, Dunstan addressed him with a solemn warning, criticizing the violent act whereby he became king and prophesying it would result in misfortune befalling the kingdom.

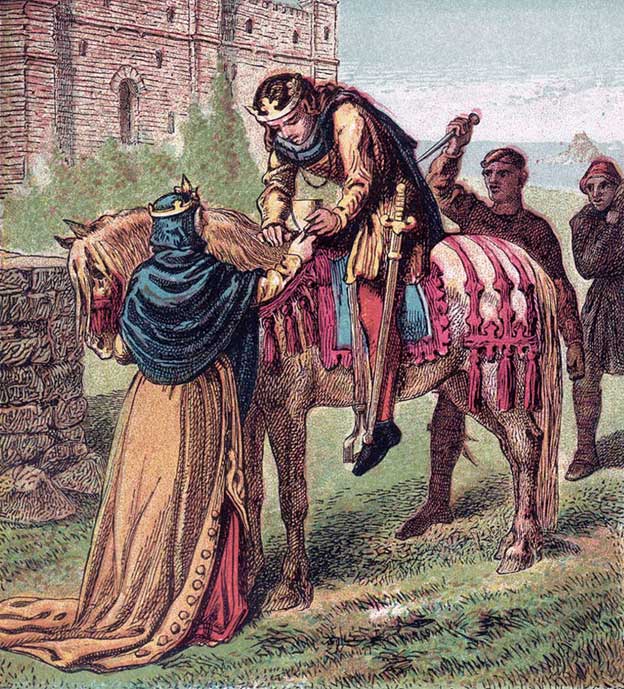

Possible self-portrait of Dunstan. From the Glastonbury Classbook, Anglo-Saxon, 10th century (Public Domain)

We can assume Dowager Queen Elfrida dismissed these warnings as merely sour grapes by a bad loser whose influence at court was now dwindling, but Dunstan turned out to be correct in his predictions. Ruling as King Aethelraed II Unraed, better known to history as Ethelred the Unready, Elfrida’s son would prove to be one of England’s most disastrous monarchs when it came to fighting the Viking armies invading his kingdom, but that is a story for another time…

Ethelred the Unready (Public Domain)

Bones of Contention

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, after his murder, Eadweard was buried at Wareham “without any royal honors” adding “No worse deed for the English race was done than this was, since they first sought out the land of Britain. Men murdered him, but God exalted him. In life he was an earthly king; after death he is now a heavenly saint. His earthly relatives would not avenge him, but his Heavenly Father has much avenged him.”

A couple of years later, his body – which was found to be ‘incorrupt’ (the lack of decay which we in modern times can attribute to natural causes, but was seen as a sign of holiness in that era) was disinterred and moved to Shaftesbury Abbey, where it as given a lavish reburial. Subsequently, with the assistance of grants on land by King Ethelred, his body was moved to an even more prominent shrine within the abbey as the cult of “St Edward the Martyr” began to grow in the early 11th century.

Edward the Martyr (Public Domain)

The very process of ‘translating’ (transferring) his body from Warham to Shaftesbury in 981 is credited with healing cripples and restoring sight to the blind. Although, Edward was never formally canonized but is recognized as a saint by the Anglican, Eastern Orthodox, and Roman Catholic churches.

Following King Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries during the English Reformation in the 16th century, many holy places were demolished, however, the nuns at Shaftesbury managed to hide St Edward’s relics and save them from desecration. Unfortunately, they were so well hidden they were not recovered until an archeological dig in 1931 and it would be a further 40 years before an osteologist (anatomist of the skeleton) confirmed them as belonging to Edward.

However, the story does not end there, as a dispute erupted between the archaeologist who found the remains, and his brother—with one wanting the relics to go to the Orthodox Church and the other wanting them returning to Shaftesbury Abbey. The dispute was finally resolved in 1984 when the relics were placed in what is now the St Edward the Martyr Orthodox Church at Brookwood Cemetery in Woking, where they are cared for by the St Edward Brotherhood of monks under the jurisdiction of a traditionalist branch Greek Orthodox church.

Killer Queen?

Lovers of irony will appreciate the fact that during the decades-long dispute over the fate of the relics of St Edward, who was killed by being stabbed in the back with a knife, his bones were stored in a cutlery box in a bank vault at the Woking branch of Midland Bank.

But what about his alleged murderess, the Dowager Queen Elfrida?

As is the way with many of these scandalous Saxon queens, in widowhood Elfrida became pious, devout and noble of character, founding an abbey Wherwell, close to site of her first husband’s murder, as a Benedictine nunnery, and late in life she retired there – supposedly to seek forgiveness for her crimes – before dying in November 1000 or 1001.

Did the Dowager Queen Elfrida seek forgiveness – or just go into hiding in a nunnery? (Public Domain)

The church chroniclers of the time remained unconvinced of her piety; one recording in the less-than-credible “Historia Eliensis" that a certain Abbot Byrhtnoth, while travelling through the New Forest, spotted Elfrida preparing magic potions that transformed her into a mare “so that she might satisfy the unrestrainable excess of her burning lust, running and leaping hither and thither with horses and showing herself shamelessly to them, regardless of the fear of God and the honour of the royal dignity.”

- The Strange Death and Afterlife of King Edmund Part 1: The Unfortunate Friendship With Ragnor Lodbrok that Led to Edmund’s Beheading

- From Saxon Sirens to Sacred Orchards: The Modern Traditions and Pagan Origins of Wassailing

- The Strange Death and Afterlife of King Edmund Part 2: Did the Martyred Saint Rise from the Grave to Kill a Viking King?

- King John: The Worst Monarch in English History?

This account goes on to claim Elfrida later attempted to seduce the Abbot to ensure his silence and when he refused “desperate not to be unmasked as a witch and an adulteress, Elfrida summoned her ladies and, together they heated up sword thongs on the fire and murdered the Abbot by inserting them into his bowels.”

Elfrida’s treatment by the church is in stark contrast to the rest of Edgar’s family. As we have already seen, Eadweard would go on to be revered as St Edward the Martyr. Edgar’s second wife Wulfthryth became venerated as St Wifrida of Wilton (there is a suggestion King Edgar originally abducted her from the nunnery at Wilton Abbey) while their daughter Eadgyth became venerated as St Edith of Wilton.

Edith of Wilton. 13th century. (Public Domain)

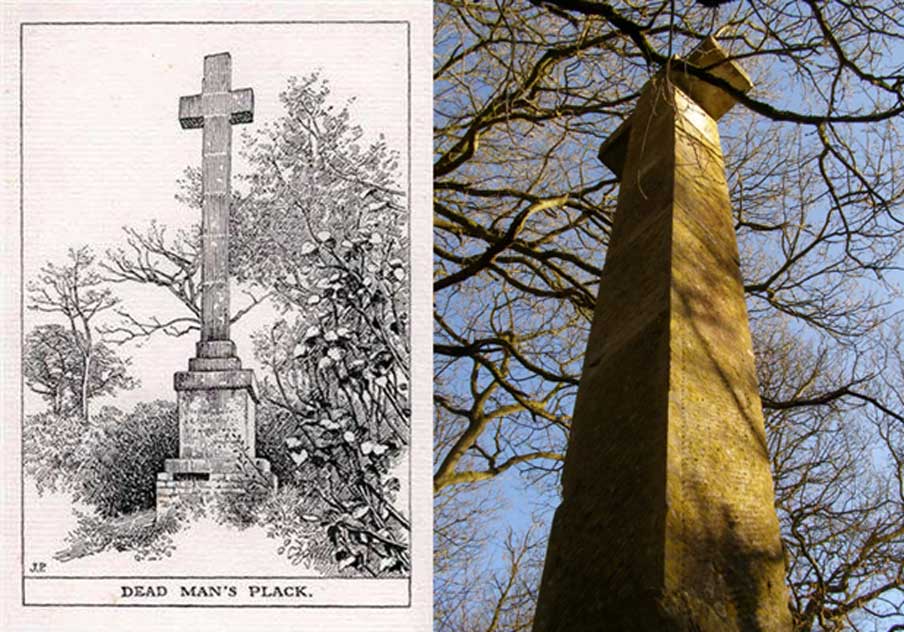

Incidentally, at Harewood Forest in Hampshire is a 19th century stone monument called Dead Man’s Plack which commemorates the killing of Aethelwold by King Edgar.

Drawing of Dead Man's Plack (Public Domain) and photo at the site, dated 1835; erected to the memory of Earl Athelwold who was killed here by King Edgar AD963. (Jim Champion/CC BY-SA 2.0)

The inscription reads:

About the year of our Lord DCCCCLXIII upon this spot beyond the time of memory called Deadman’s Plack, tradition reports that Edgar, surnamed the peaceable, King of England, in the ardour of youth love and indignation, slew with his own hand his treacherous and ungrateful favorite, owner of this forest of Harewood, in resentment of the Earl’s having basely betrayed and perfidiously married his intended bride and beauteous Elfrida, daughter of Ordgar, Earl of Devonshire, afterwards wife of King Edgar, and by him mother of King Ethelred II. Queen Elfrida, after Edgar’s death, murdered his eldest son, King Edward the Martyr, and founded the Nunnery of Worwell.

Charles Christian is a professional writer, editor, award-winning journalist and former Reuters correspondent. His non-fiction books include Writing Genre Fiction: Creating Imaginary Worlds: The 12 Rules

Charles has presented a variety of excellent talks with AO Premium on ancient legends, surprising folklore, and creepy and cool traditions:

|

-

Top Image: Some Saxon Queens had killer reputations. (Public Domain);Deriv.