Zheng He, The Eunuch Who Became A Ming Dynasty Admiral

In 1127, the Song Dynasty (960 - 1279) lost control of northern China and, with it, access to the Silk Road and Persia's riches. After overthrowing the Song Dynasty and rising himself to the imperial Chinese throne in 1279, the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan had millions of trees planted and new shipyards built. Kublai Khan soon commanded a fleet of thousands of ships that he then sent out to attack Japan, Vietnam and Java. Although these naval offensives did not gain land, it gave China an opportunity to gain control of the sea lanes from Japan to Southeast Asia.

Japanese samurai boarding Mongol Yuan dynasty ships in 1281. (Public Domain)

Through Kublai Khan’s ambition, the Mongols afforded merchants new preeminence which led to a flourishing maritime trading. However, on land, the Mongols struggled to set up a stable system of government and gain the allegiance from the people they had conquered. After decades of internal revolt in China, the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty collapsed in 1368 and was succeeded by China’s Ming dynasty that went on to rule from 1368 to 1644. The Hongwu Emperor, the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty who reigned from 1368 to 1398, favored limited overseas contact with naval ambassadors charged with securing tributes from an increasingly long list of vassal states which included Brunei, Cambodia, Korea, Vietnam and the Philippines, thereby ensuring that lucrative profits did not fall into private hands.

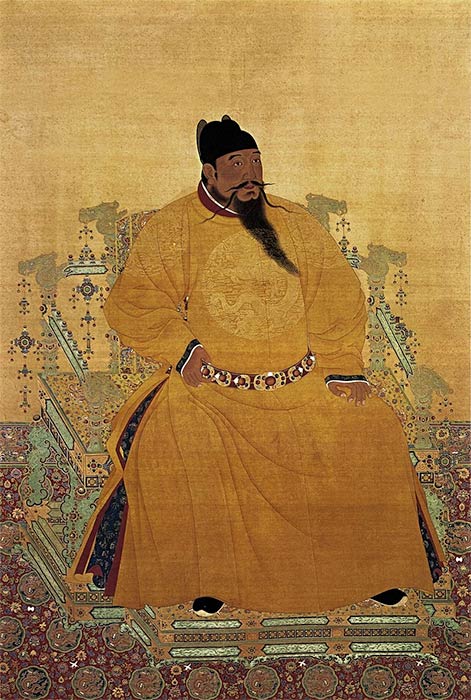

Emperor Chengzu of the Ming Dynasty, commonly called the Yongle Emperor, sitting in the 'Dragon' chair. Taibei National Palace Museum (Public Domain)

The Yongle Emperor, the third Ming emperor, took the restrictive maritime policy even further by prohibiting private trade and pressing for Chinese domination of the South Seas and the Indian Ocean. The beginning of his reign saw the conquest of Vietnam and the establishment of Malacca as a new sultanate, ruling the entry point of the Indian Ocean which was an extremely strategic ruling position for China. The emperor planned to assemble a grand fleet to conquer the trading routes that unified China with Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. He selected his eunuch Zheng He to lead the voyage.

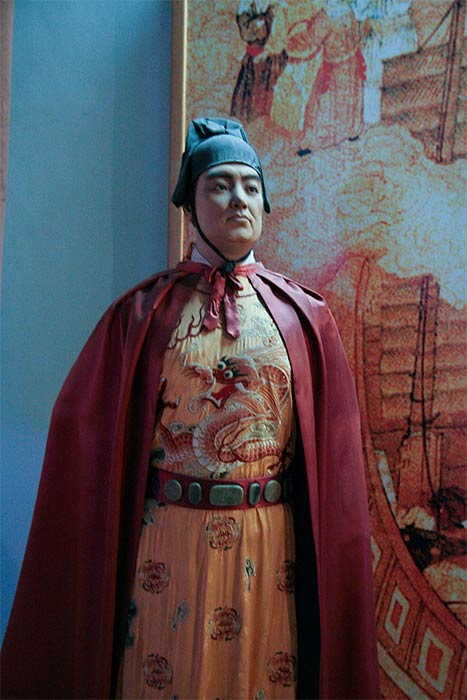

Zheng He statue in the Quanzhou Maritime Museum (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Early Life of Zheng He

Zheng He was born in 1371 with the name Ma He to a wealthy Hui (Chinese Muslim) family in the Yunnan Province, the last Mongolian-hold in China. The Hui people are an ethnoreligious East Asian community composed predominantly of Chinese-speaking Islamic adherents. The Hui people spread throughout China, primarily in the country 's northwest provinces and the Zhongyuan region. Both Ma He’s father and grandfather were hajji - Muslims who made the hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca in accordance with the ‘Five Pillars of Islam’. The family name Ma was taken from the Chinese rendering of the name Muhammad, the Islamic prophet. Understandably, the culture surrounding Ma He's childhood would have evolved primarily from Islamic practices which included observing Islamic dietary laws by refusing to consume pork, the most common meat consumed in China. The traditional Hui clothing also differed from the Han Chinese in that some Hui men wore taqiyah (white caps) and some women wore headscarves.

In 1381, when Ma He was around 10 years old, the Yunnan province was reconquered by Chinese forces led by Ming Dynasty generals who had overthrown the Mongols in 1368. Ma He's father was killed in the battle that ensued, and the young Ma He soon found himself among the boys who were captured by the Ming army. Ma He was castrated as was customary for juvenile captives. He survived this ordeal and was forced to serve in the army.

A group of eunuchs. Mural from the tomb of the prince Zhanghuai, 706 AD. (Public Domain)

Castration in Context

Although recordings of the early years of Zheng He rightfully focused on his rise to power with special emphasis on his voyages, it is useful to look at Zheng He’s capture in context to appreciate his extraordinary life and achievements.

Through retellings of Chinese history and the popularity of the wuxia (‘martial heroes’) genre of Chinese fiction, the impression that one might have about the rise of a eunuch to a position of power is that it was a natural progression for a eunuch who worked in the palace. However, powerful eunuchs were more the exception rather than the rule. For centuries in ancient China, the only people outside the imperial family who were permitted into the private quarters of the Forbidden City were castrated. At the height of their numbers during the Ming dynasty, the number or eunuchs employed by the emperor reached 100,000 eunuchs. This number decreased to about 70,000 eunuchs at the end of the Ming dynasty. Apart from captives like Ma He, there were also tens of thousands of people who voluntarily traded their reproductive organs for a promise of that elusive access to the emperor, which made some politicians very wealthy and powerful. Therefore, making a historical impact as a eunuch was a privilege granted to the exceptional few and an extremely unlikely achievement for a 10-year-old Muslim captive from Yunnan.

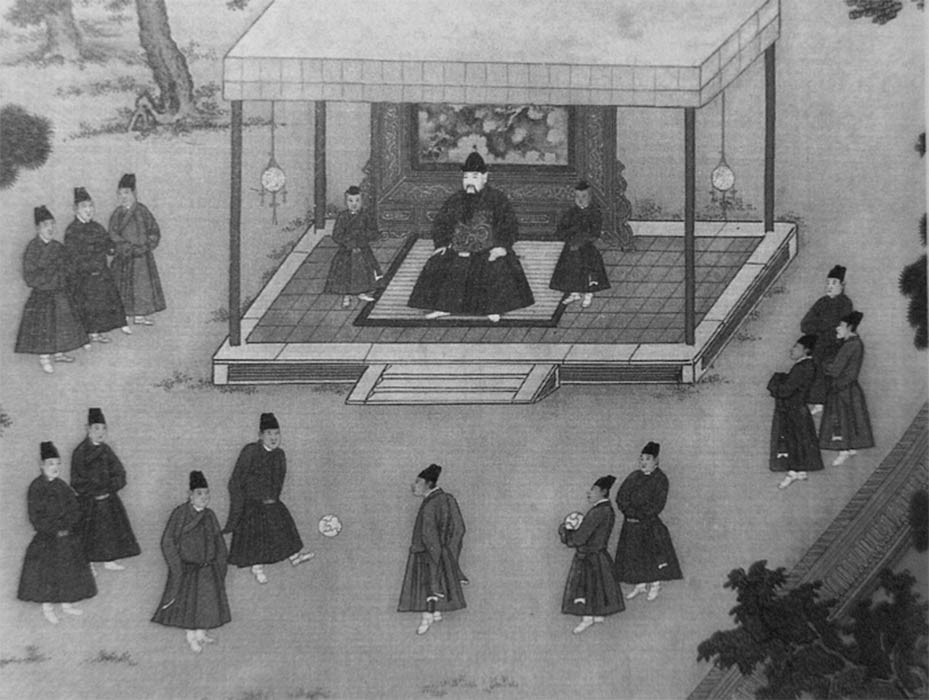

The Yongle Emperor observing court eunuchs playing cuju, an ancient Chinese game similar to soccer. (Public Domain)

Many young boys who did not even start as captives endured the painful procedure to become eunuchs. They were volunteered by their parents or guardians, because they came from poor families who could not repay their families’ debts, to being emasculated and sold to the local or royal court. The surgeries were typically conducted during spring or early summer to avoid extremely hot or cold temperatures, mosquitoes and flies. After the surgery, the new young eunuch was unable to wear clothes for about a month. Before the procedure, the surgeon asked the applicant a few questions to confirm the candidate’s willingness to be a eunuch. Of course, the comparatively safe procedure done by a surgeon and the confirmation questions only applied for voluntary eunuchs.

- The Four Great Beauties, and the Arts of the Courtesans in Ancient China

- Scythian Priesthood of Fierce Fighting Eunuch Shamans of the Snake Goddess

- The Hidden Mastermind and Warrior Queen Behind an Empire’s Golden Age

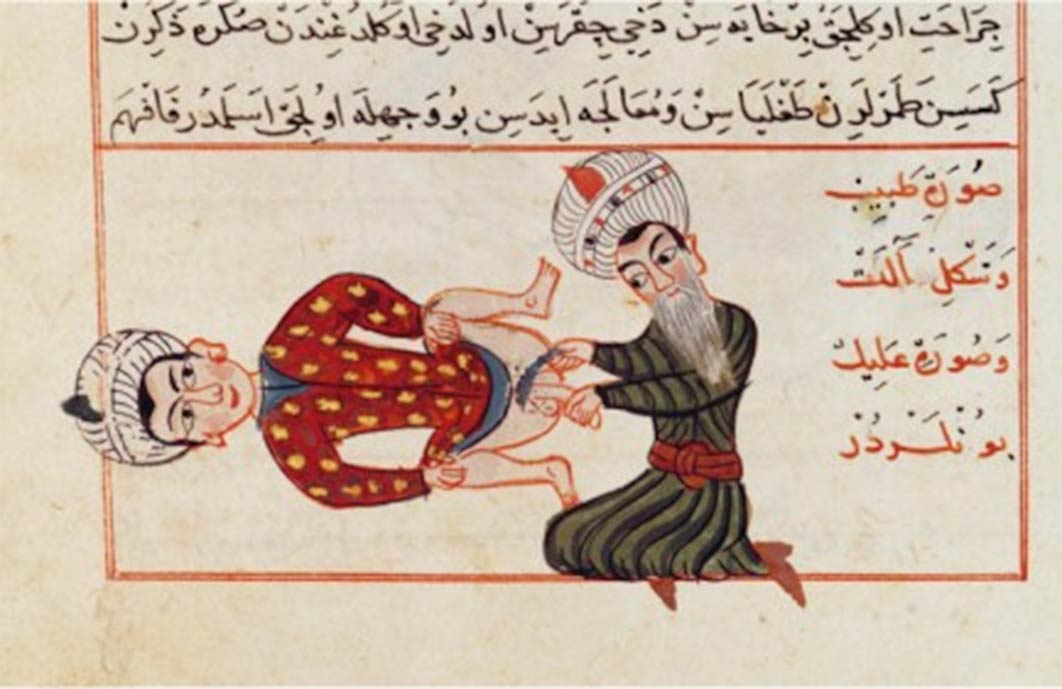

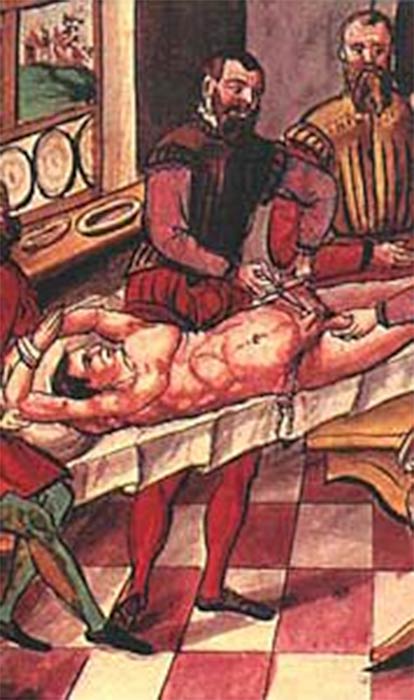

The process of castration experienced by Ma He as a child captive was more dangerous. The Cambridge Dictionary defines the word castration as: “the process of removing the testicles of a male animal or human”. However, in ancient times, castration actually involved emasculation or the total removal of all the male genitalia, risking great danger of death due to bleeding or infection.

A medical illustration by Sharaf ad-Din depicting an operation for castration. (c. 1466) (Public Domain)

Not as much is known about emasculation done to prisoners or criminals in ancient China, but to put the practice in the context of punishment, emasculation in the Byzantine Empire was looked at with the same fear as a death sentence. In China, emasculation is included in 五刑 (wǔ xíng, the Five Punishments). The Five Punishments was the collective name for a series of severe physical penalties enforced by the legal system of ancient China. Apart from the death penalty, which was the most severe of the five punishments, the remaining four punishments were designed to bring about damage to the body which would mark the convict for life. For men, the five punishments included: Mo, where the offender would be tattooed on the face or forehead with permanent ink; Yi, where the offender's nose was cut off without an anesthetic; Yue involved amputation of the left or right foot or both; Gong, where the male offender's reproductive organs were removed and the offender was sentenced to work as a eunuch; and Dà Pì, which was a death sentence by quartering the body, boiling alive, beheading, slow slicing and many others.

In 甲骨文 (jiaguwen, ‘plastron bone inscriptions’), remnants from the Shang dynasty (1600 - 1046 BC), penal emasculation is written simply as a picture combining a knife and a penis. When this punishment is applied to a rebellion, it was often combined with 連坐 (lianzuo, ‘collective liability’) leading to whole families being emasculated.

The procedure of castration as punishment during the 16th century.(Public Domain)

Early Life At The Court Of Zhu Di

By 1390, young Ma He had distinguished himself as a skilled junior officer. Soon, he was brought to serve in the court of Zhu Di, the future Ming emperor later to be titled the Yongle Emperor, who was only 11 years his senior. Over the next decade, Ma He received military training, and gradually became a trusted assistant and adviser to the emperor. He also served as a bodyguard protecting Zhu Di during many battles against the Mongols. In 1402, Zhu Di forcefully took the throne from his nephew and proclaimed himself the Yongle Emperor (The title of Yongle means ‘Perpetual Happiness’). He made his companion Ma He the Grand Eunuch who functioned as the director of palace servants (similar to a modern-day chief of staff), and changed Ma He’s name to Zheng He in commemoration of his role in battles to win the throne on his behalf. Zheng was the name of the Yongle Emperor’s favorite warhorse. The Yongle Emperor went on to rule from 1402 to 1424.

Yongle Emperor of Ming dynasty (Public Domain)

Part of Zheng He’s work as the Grand Eunuch was being responsible for palace construction and repairs. He was also required to learn more about weaponry and ship building. His understanding of ships would become very important to his future as, in 1403, Zhu Di ordered the construction of the Treasure Fleet – a fleet of trading ships, warships and support vessels. He intended this fleet to travel across the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. To command this fleet, the Emperor chose Zheng He. Zheng He would serve as the imperial court's official envoy to foreign countries.

The Uncommon Rise of Zheng He

Certain eunuchs gained immense power. The employment of eunuchs as high-ranking civil servants was justified by the fact that, since they were incapable of having biological children, the eunuchs would not be tempted to seize power and start a new dynasty. However, despite this seemingly close relationship to the pinnacle of power in ancient China, a rise to power did not commonly happen to those who were emasculated as prisoners. Men sentenced to emasculation in the Qin (221 - 206 BC) and Han (202 BC – 220 AD) dynasties were typically utilized as eunuch slaves and condemned to perform forced labor. The Qin government also confiscated the property and enslaved the families who received castration as a punishment. Men punished with emasculation during the Han dynasty were also used as slave labor.

General Zheng He statue in Sam Po Kong temple, Semarang, Indonesia (22Kartika/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

The royal palace of the Ming dynasty acquired eunuchs from both domestic and foreign sources. Those who came from foreign sources could count among the tributes from a many small countries around China or were taken by force from the people or places who were considered the enemies of the dynasty. Therefore, similar to Ma He’s experience as a child, they were emasculated as a means of punishment when they were captured by the Ming army.

Eunuchs who managed to gain employment in the imperial palace would play a critical role in the operation of the palace. Their responsibilities varied in significance and included every aspect of the everyday routine in the imperial palace such as procuring copper, tin, wood and iron. Their tasks also included repairing and constructing ponds, castle gates and the mansions in the living quarters of imperial relatives. They prepared meals for the great number of people in the palace. They also looked after the animals in the palace. Thus, the eunuchs' work was the cornerstone of the palace daily operation and centered around the comfortable lives of the emperor and his relatives. However, this did not always mean that it guaranteed the eunuchs’ rise to prominence.

As proven by the advancement of Zheng He, rising to higher ranks for eunuchs may have been difficult, but not impossible. The Ming dynasty saw the gradual change in the duties of eunuchs. In the rule of Emperor Hongwu, the emperor decreed that the eunuchs were to be kept in small numbers and of minimal literacy in case the eunuchs attempted to seize power. However, it was not until the later generations of emperors, such as the Yongle Emperor, that eunuchs such as Zheng He were trained and educated to enable them to be elevated to the ranks of personal secretaries to ministers or emperors.

Some of the major long-distance military-diplomatic expeditions of the Yongle and Xuande reigns of the Ming Dynasty (1402-1435). Red circles: cities thought to have been visited by the fleets of Zheng He, or the elements of the fleet, on the seventh and/or earlier voyages. Green circles: important places in the biography of Zheng He (CC BY-SA 1.0)

Zheng He’s First Voyage

The first emperors of the Ming dynasty attempted to demonstrate their powers by initiating campaigns to defeat any domestic or foreign threats. The Yongle Emperor was particularly aggressive in this regard and personally led major campaigns against Mongolian tribes to the north and west. He also revived the traditional tribute system where countries on China's borders agreed to recognize China as their superior and regularly gave gifts of tribute in exchange for certain benefits, such as military posts and trade treaties.

The Yongle Emperor sent its most respected generals to the north to deal with the Manchurian people, the east to the Koreans and Japanese, and the south to the Vietnamese. However, for ocean expeditions to the south and west, he agreed that China would use its extremely advanced technology, and all the resources that the state had to offer. Lavish expeditions were mounted to overpower and persuade the world of Ming supremacy beyond any doubt. Zheng He was promoted to serve as the imperial court's ambassador to foreign countries and thus commenced his travels.

This portrait of Zheng He was published about 1600 in a fictionalized account of Zheng He's sea voyages. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Maritime History. (Public Domain)

Zheng He's travels can be split into two phases: the first three travels, and the next four to seventh. The goal of the first phase of Zheng He's journeys was to secure the status of the emperor as well as show off China's wealth and military might. The goal for the second phase was to develop friendly international relations with other countries while at the same time placing greater emphasis on tributary trade.

Despite the emperor’s blessings, Zheng He still experienced opposition. The Ming court was split into several groups, most strongly between the pro-expansionist voices led by the influential eunuch groups who had been responsible for the policies that supported Zheng He's travels, and the more conventional Confucian court advisers who called for and insisted on frugality. Nevertheless, Zheng He prepared for his first voyage on behalf of his emperor.

Zheng He’s fleet. Cheng Ho Cultural Museum – Exhibition (CCO)

While the eunuch captains and admirals of these great Chinese ships were able men, Zheng He also recruited his crews from the lowest levels of society. Most of the seamen who joined Zheng He in his travels were criminals who preferred a life at sea as crewmen to a prison sentence. The crew were issued with a uniform which consisted of a knee-length white robe, food and wine. The fleet had a total of about 208 vessels which included 62 treasure ships and over 27,800 crew members. The admiral 's staff comprised of 180 health officers, with one medical officer for every 150 people on each ship. The treasure ships maintained a diverse and healthy diet, but the perils of sailing across uncharted waters meant that life expectancy was short as only one in ten people returned from the journeys. Those who had survived the treasure fleet 's earlier voyages were well rewarded. They were released and sometimes granted pensions or endowments.

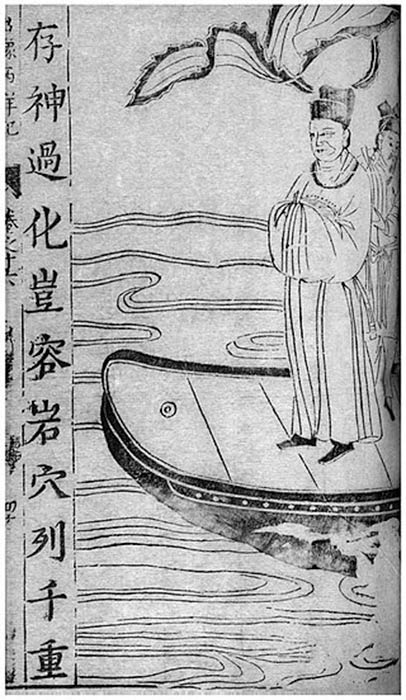

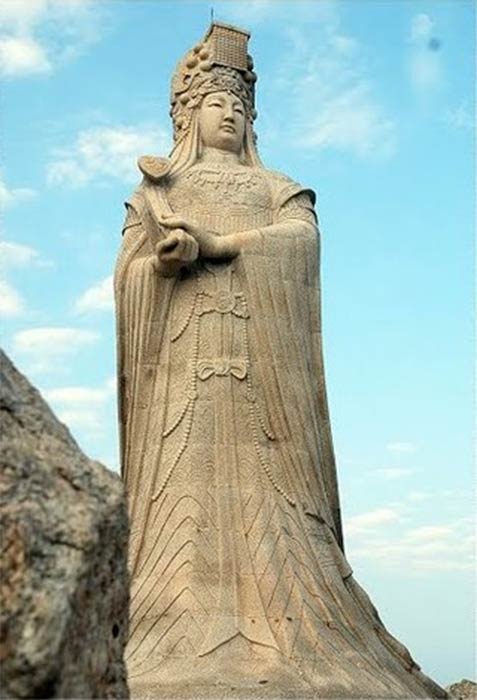

Each of the ships in Zheng He’s fleet had a small cabin dedicated to Ma Tsu, the goddess of the mariners, and prayers to Ma Tsu were said every evening before supper. When the crew disembarked in foreign lands, they brought round bronze mirrors with an eight-spoke Taoist wheel on the reverse to fend off evil spirits.

Ma Tsu Mariner’s goddess (Jet.Xu/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

The crew elite were the navigators and compass-men who worked, lived and dined away from the rest of the crew, separated by an enclosed little bridge. The junks also carried every definition of the artisans and craftsmen capable of performing any task. Caulkers, sailors, scaffolders, carpenters and tung oil painters kept the ships in good repair on their long journeys on the distant seas. Tone-carvers and stonemasons were also employed in order to leave lasting legacies of the voyages of the ships around the world.

Zheng He began his first voyage in July 1405. They set sail from Jiangsu Province's Liujiagan Port in Taicang and headed westwards. They sailed to Vietnam, met the king and gave him gifts. The fleet then moved to Java, Sumatra, Malacca, crossed the Indian Ocean and sailed west to Cochin and Calicut, India. The several stops included spice trading and other goods, as well as visiting royal courts and establishing relationships on behalf of the Chinese emperor. Zheng He's first voyage came to an end in 1407 when he returned to China. Zheng He went on to devote 28 years of his life to the great cause of navigation.

Martini Fisher is an Ancient Historian and author of many books, including ”Time Maps: Gods, Kings and Prophets” | Check out MartiniFisher.com

Top Image: Zheng He’s fleet Cheng Ho Cultural Museum – Exhibition (CC0)

References

Asia for Educators. 2020. Ming Voyages. Available at: http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/china_1000ce_mingvoyages.htm

Brezina, C. 2016. Zheng He: China’s Greatest Explorer, Mariner, and Navigator. Available at:

Brown, C. S. 2020. Zheng He Chinese Admiral. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/big-history-project/expansion-interconnection/exploration-interconnection/a/zheng-he

Damiani, M. 2014. How to create a eunuch – the procedure. Available at:

https://china-underground.com/2014/01/20/how-to-create-a-eunuch-the-procedure/

Ding, J. et. al. 2007. An Important Waypoint on Passage of Navigation History: Zheng He’s Sailing to West Ocean,TransNav. International Journal on Marine Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation, Vol. 1, No. 3,

Folch, D. 2020. Zheng He naval explorer sailed the treasure fleet. Available at:

Graham-Harrison, E. 2009. China's last eunuch spills sex, castration secrets. Available at:

https://www.reuters.com/article/idINIndia-38511820090315

Lo, J. P. 2020. Navy Military force. Available at : https://www.britannica.com/topic/navy

Theobald, U. 2000. Gong. Penal castration. Available at : http://www.chinaknowledge.de/History/Terms/penal_gong.html

January 20, 2023, 6:13 pm

Gemwise

It's amazing how advanced the Chinese were and how quickly the fell behind after closing China off from the world