Loves Of The Lady Of The Labyrinth: Ariadne Powerful Minoan Goddess

In the Myth of the Minotaur, if not for the ministrations of the humble Princess Ariadne, Theseus—the Greek hero—would not have had a prayer. Although often portrayed as a mere maiden, truth be told, providing back-up for a leading man was the very least of her qualities. Springing from the heavens, Ariadne’s origins beckon from the primordial mist of Bronze Age Minoan Crete where she was the overarching mother goddess in the Minoan pantheon—the all-important fertility goddess who is believed to have answered to such titles as goddess-on-earth, weaver of life and mistress of the labyrinth.

Minoan Snake Goddess (©Courtesy Micki Pistorius)

Ariadne Minoan Fertility Goddess

With the destiny of mortals in her hands, Ariadne was considered a bright goddess, often compared to Demeter—whose celestial origins were from Crete as well. In some ways Ariadne is analogous both to the goddess of the harvest—and her daughter Persephone—queen of the underworld. Predating patriarchy, the mother goddess’s role was paramount—in agricultural societies religion was centered on fertility and everything was centered on religion. Because Minoan Crete was a matrilineal society with women leading lives of independence, like all goddesses in the Minoan pantheon, Ariadne ruled alone without a male consort. Toward the close of the Minoan civilization—with the Mycenaeans’ influence keenly felt—Ariadne began to be accompanied by a young male consort. Her insignia, the labyrinth—a square or circular structure with multiple circuits spiraling to the center and back again—figures prominently in her mythology and is believed to have been a place of initiation where mortals moved from one realm to another with the bull-god—the Minotaur (Hades-like)—occupying its deepest and darkest center.

- The Descent of Ariadne: Minoan Queen of the Dead to Mistress of the Labyrinth?

- Pasiphae: Daughter of the Sun, Wife of a King, and Mother of the Minotaur

- The Legendary Cretan Labyrinth Cave: Inspiration for the Story of King Minos and the Labyrinth of the Minotaur?

Patriarchal Mycenaeans

The decline of the Minoan Civilization was accompanied by the expansion of the Mycenaeans—as is often the case when one culture subsumes another—when the Myceneans overtook the Minoans in about 1400 BC, they recast the Minoan myths; the invader gods married the indigenous goddesses replacing matricentric elements with patriarchal ones. By rewriting mythology, the Mycenaean Greeks provoked the systemic suppression of goddess worship which would encourage the widespread denigration of women. But the patriarchal reformulating of the tales did not stop with the Mycenaeans, it continued apace into the Greek and Roman cultures. By reviewing the myths surrounding Ariadne, one exposes the patriarchal tropes that have dogged her many guises for thousands of years.

Pasiphae by Giulio Romano. (Public Domain)

Pasiphae’s Conception Of The Minotaur

Ariadne is best known from a Mycenaean era myth in which the all-important great mother goddess is reduced to an unassuming princess offering succor to the invading Theseus, the legendary first hero-king of Athens. The tale begins when Poseidon—god of the earth and sea—gifts a rare white bull to King Minos of Crete with the expectation of it being sacrificed in his honor. Ever greedy to have the prized bull play stud in his herd, Minos tries to pull a fast one on the god by sacrificing a lesser bull in Poseidon’s honor instead. Because he was all-seeing and all-knowing, an infuriated Poseidon casts a spell on Minos’ Queen Pasiphae so she would fall hopelessly in love with the striking snow-white bull. The hex worked. In fact, Pasiphae’s desire for the bull was so strong that she enlisted the help of the famed artificer, Daedalus, into crafting a wooden cow with a cowhide covering so that she could copulate with the beast. The product of their coupling was the Minotaur, a monster who was a cross between human and bull. Uncared for and unloved, the Minotaur was confined to the labyrinth—which was, once-again, designed by the perennial inventor.

Theseus dragging the Minotaur from the Labyrinth. Tondo of an Attic red-figured kylix, (ca. 440-430 BC). Vulci. British Museum (CC BY-SA 2.5)

The story leading up to the Minotaur’s malevolence toward Athenians is illustrative of a time of high tension between Minoan Crete and Athens; when Crete was the powerhouse of the Aegean and Athens a mere fledgling state. Legend has it that King Minos’ son Androgeus had been treacherously killed by Athenians for nothing more than taking all the prizes in their Panathenaic Games. In retribution for his death, each year Athens had to send seven young men and seven young women as tribute to Crete. Essentially hostages, the unarmed Athenian youth were placed in the labyrinth where they would either hopelessly lose their way in its endless sinuous passages or be devoured by the man-eating Minotaur confined there. This burdensome tribute went on for years until Theseus, son of Aegeus, King of Athens steps up to the plate volunteering to be one of the seven male victims.

‘Ariadne and Theseus’ (1657) by Willem Strijcker. ( Public Domain )

Ariadne And Theseus

Finally, Ariadne enters the myth. Daughter of Minos and Pasiphae thus sister to the Minotaur she is instantly besotted with the Athenian hero and promptly forsakes her family for the stranger from Athens. She arms Theseus with a sword to kill her brother, the Minotaur. Then to escape from the complex Daedalean maze, she gives him a ball of thread, ingeniously advising him to tie one end of the thread at the entrance and let the thread unspool as he tunnels deeper into the labyrinth’s undulating paths. Ever the headliner, Theseus succeeds in his quest to destroy the Minotaur and follows the thread back to the entrance where the love-struck Ariadne awaits. From there they sail off together to Athens but before getting there they make a detour to the island of Dia (Naxos) where Theseus sees fit to abandon Ariadne.

‘Ariadne’ by Herbert James Draper (1905). ( Public Domain )

Many have chimed in about the possible reasons for the Greek hero defaulting on his Minoan savior feat. Both Hesiod (circa 750 BC - 650 BC) and Plutarch (50 AD – 120 AD) contrive that Theseus left Ariadne because he was in love with Aigle, the goddess of good health. In Euripides’ (480 BC- 406 BC) lost play Theseus the theme of the play suggests that Theseus—much like Aeneas deserting Dido in the Aeneid—left the Minoan princess at the provocation of father-serving Athena herself (the patron goddess of Athens) because he had a heroic career ahead of him and the exotic Ariadne could prove a distraction. Along these same lines, Latin author and scholar, Hyginus (64 BC -17 AD) suggests that Theseus thought Ariadne would bring disgrace on him in Athens—presumably because she was a foreigner. The notion of Greek identity began to take form with the advent of conquering and/or colonizing foreign lands beginning in the eighth century BC when they began defining themselves—xenophobically—vis a vis everyone else.

Medea boiling the ram before Pelias. Drawing after an Attic black-figure amphora. British Museum (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Ariadne And Medea

At this point the story begins to resemble another Mycenaean-era myth where lack of parity between the couple is hallmark. In Jason and the Argonauts, Medea, another goddess cum princess from a foreign land (Colchis--present-day Georgia) also acts against her better interests by abandoning her royal family for the Greek hero, Jason, who ultimately deserts her. To seize the Golden Fleece, Medea helps Jason every step of the way, even at the expense of her father and the murder of her brother. Although their stories differ in substance, both women share exploitation as a recurrent theme when they are cast aside after wearing out their usefulness to the hegemonic Greek heroes. Demonstrating the lack of parity between the Greeks and their conquests, the women—often the spoils of war—represent the subjugated from vanquished lands while Theseus and Jason, play the roles of heedless invaders—symbolic of the colonizing Mycenaean Greeks—plundering the resources of the defeated while fleeing with its most valuable possessions. Being vanquished, however, is not the only similarity of the two women.

Unlike her counterpart from Colchis, Ariadne is not known for vengeance yet in a surviving passage attributed to the scorned Ariadne from Euripides’ Theseus is the line: “and yet I will tell a tale worthy of blame...” Hellenistic poet, Catullus (84 BC-54 BC) expands on this theme in his epic Poem 64, where taking a page from Medea, Ariadne calls for vengeance against her Greek hero. Before he had left for Crete, Theseus had promised his father that if his mission were a success, he would hoist a white sail in place of the black sail which in previous years symbolized the sacrificed 14 Athenian youths. On account of Ariadne’s curse, when Theseus leaves the distraught princess, he forgets to hoist the white sail. Upon sight of the black sail, Aegeus—believing his son dead—jumps to his death into the sea, which henceforth would be named in his honor: the Aegean. Just as the gods in Euripides’ Medea aid Medea in her quest for revenge, so Catullus tells of how Zeus comes to Ariadne’s defense. Yet Ariadne is not good at vengeance. When Medea had revenge on Jason, she destroyed his bride, his progeny and his future, whereas Ariadne’s act of vengeance would make Theseus king of Athens.

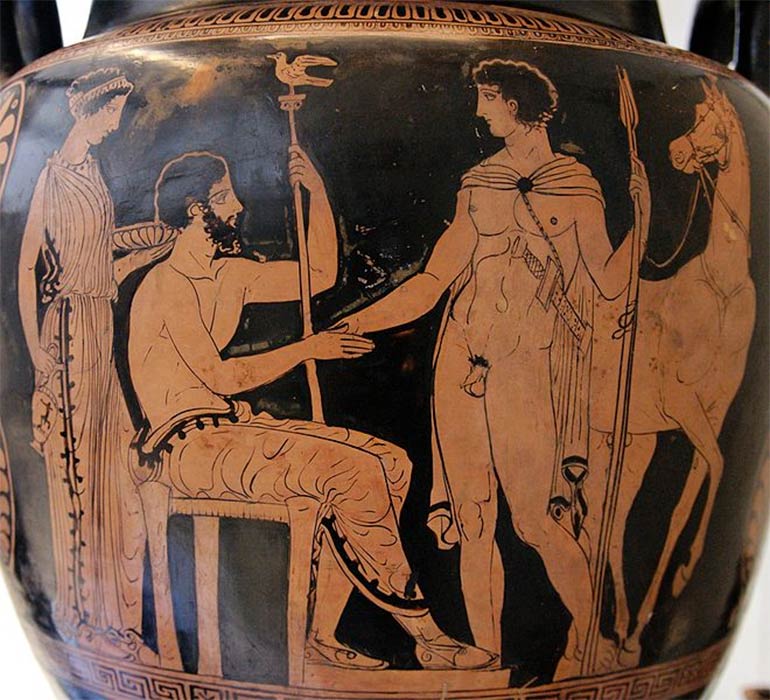

Theseus arriving at Athens and being recognized because of his sword by Aegeus. Apulian red-figured volute-krater, (ca. 410–400 BC.) Ruvo. British Museum. (CC BY-SA 2.5)

Along with the similarities between the two scorned women, as granddaughters of the Sun god, Helios, both women possess supernatural powers and as such represent vanquished deities as well—some suggest Medea also may have been a pre-patriarchal goddess. In his seminal book The Masks of God: The Occidental Mythology Joseph Campbell asserts: “It consists simply in terming the gods of other people demons, enlarging one’s own counterparts to hegemony over the universe, and then inventing all sorts of great and little secondary myths...to validate not only a new social order but also a new psychology.” At its heart, the Myth of the Minotaur is about a Cretan monster more bull-like than human who devours Athenian young. Not lost is the fact that bulls in Minoan Crete were not only objects of veneration but quite possibly used in their sanctified rituals as well. Yet denigrating a sacred animal was only part of their discrediting. More powerful still was their marginalization of Ariadne by transforming the Minoan great mother goddess into a lovesick maiden who is subservient to the Greek hero, Theseus. Reduced to a mere conduit for Theseus’s success, the truth is if not for the help of Ariadne, Theseus would be a mere postscript—neither king nor hero. Yet Theseus is the star of this story—Ariadne only a bit player. After renouncing her family and homeland Theseus abandons her—while she is sleeping—leaving her for dead on the alien and desolate island. In some versions, a heartbroken Ariadne commits suicide.

Dionysus discovers Ariadne on the shore of Naxos. The painting also depicts the constellation named after Ariadne by Titian (1523) National Gallery (Public Domain)

Consort Of Dionysus

At this point the reveler and bon vivant, Dionysus—god of the grape harvest enters the stage. According to one tradition, Theseus was compelled to leave Ariadne because of threats made by the god Dionysus—who wanted Ariadne for his own. Left with little in the way of choice, Ariadne acquiesces. Put another way, a sleeping Ariadne resembles an unaware Persephone picking flowers while whisked away by the lord of the underworld—her own Uncle Hades—to wed in the abyss. Seen this way, marriage is a violation, which is precisely how the historian Pausanias (115 AD -180 AD) expresses the marriage of Dionysus and Ariadne: “Ariadne asleep, Theseus putting to sea and Dionysus arriving to rape Ariadne.” Here Ariadne is like all Greek girls, whose marriages—arranged by their fathers to total strangers typically twice or three times their age—must have felt like a sort of rape. Thought to have originated in Thrace or Asia Minor, Dionysus is a foreign deity believed to have been amongst one of the older chthonic (subterranean) gods known for their roles in fertility. Ariadne, no longer a Minoan princess, is once again a fertility goddess whose sleeping—suggestive of the period where the earth lies dormant—is analogous to Persephone going underground for a few months each year. Unlike the love story between the Greek hero and his love-struck aid, the union between Ariadne and Dionysus resolves itself each year. Moreover, Dionysus bestows Ariadne with a gift from the gods. A gold crown, formerly Aphrodite’s—forged by Hephaestus—with red gems shaped like roses would eventually be placed among the stars becoming Corona Borealis (Crown of Lights) in the night sky.

Artemis pouring a libation. Attic white-ground lekythos, (ca. 460–450 BC) Eretria. Louvre (Public Domain)

Demise Of Ariadne

But there is a twist to the story. In Homer’s Odyssey, Artemis—the virgin goddess of the hunt and of chastity, renowned for brutally punishing wayward women—slays a mortal Ariadne for her infidelity to Dionysus who was, evidently, her husband all-along. From the Odyssey the phrase is interpreted as “on the denunciation of Dionysus,” apparently Dionysus was upset because Ariadne defiled his grotto by her love for Theseus. Never mind that Dionysus himself was a notorious seducer. Patriarchal to its core, the Odyssey—perhaps originally composed in the oral tradition as early as the Greek Dark Ages (between 1200-850 BC)—is at heart a story about Odysseus’ adventures and numerous infidelities in his ten-year long homecoming while at home pining for him, his wife—Penelope—is content to stitch away the years. Ariadne’s infidelity, however, can be explained in the context of fertility and occurs during the unfertile time of the year, when the fertility god’s seed lies dormant. At that point the fertility couple separates, and the goddess goes away—perhaps harkening back to an era before marriage when women had more agency in their reproductive lives. Finally, Ariadne either sleeps or dies during the dormant season. After all, for a fertility goddess, sleeping and dying are much the same thing.

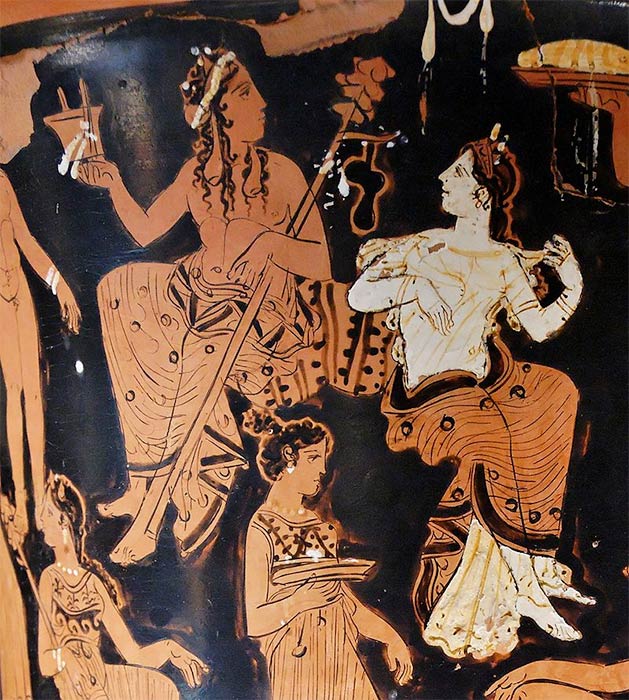

Dionysos and Ariadne. Detail from the side A of an Attic red-figure calyx-krater. (ca. 400-375 BC). From Thebes. (Public Domain)

Make no mistake, unlike her previous manifestation in the Minoan pantheon, Ariadne is now merely the wife of a fertility god. Myths abound about Dionysus’ exploits and adventures without Ariadne, yet when Ariadne is mentioned at all in these myths, it is only in relation to Dionysus. When Dionysus returns to her, their marriage is made sacred each year amidst orgiastic celebrations—Ariadne is reborn, and the planet is made fruitful again. According to Walter Burkert’s seminal book Greek Religion, the celebration of the sacred marriage between Dionysus and Ariadne was called the Anthesteria and it commemorated the king, Theseus, giving his wife, Ariadne, to the god. Moreover there were two Ariadne festivals on the island of Naxos, one joyful, the other mournful. “The marriage with Dionysus stands in the shadow of death,” Burkert affirms. As with all fertility festivals, death—an aspect of life’s regeneration, is implicated in the revelry.

Perseus holding the head of Medusa, by Benvenuto Cellini, Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence; Italy (Public Domain)

Death calls again in another myth associated with the fertility couple when Dionysus finds himself at war with his nemesis—Perseus, King of Argo—and the Argives. Perseus, it should be remembered, was made famous for beheading Medusa—while she slept. One of the three Gorgon sisters, Medusa’s gaze would turn men to stone. Some assert that Medusa may have once been a pre-patriarchal goddess herself which could be reason enough for her slaying by the patriarch. According to the epic poet Nonnus (circa 400-500 AD) in his Dionysiaca a “frail,” and evidently mortal Ariadne, turned to stone when “raging Perseus” mistakenly strikes her in battle with a spear. There are, however, inconsistencies in the myths. Time and again throughout these later myths, Ariadne is referred to as mortal even though in another tradition, Dionysus descended into the underworld to retrieve her and take her back with him to Olympus as his immortal wife. She proves, however, to be more mortal than immortal when according to Pausanias the goddess is laid to rest in an “earthenware coffin.” Finally, again in Dionysiaca Nonnus revives her weepy shade: “Dionysos, you have forgotten your former bride: you long for Aura, and you care not for Ariadne. O my own Theseus, whom the bitter wind stole! O my own Theseus whom Phaedra (Ariadne’s sister) got for a husband! I suppose it was fated that a perjured husband must always run from me…Alas, that I had not a mortal husband, one soon to die; then I might have armed myself against lovemad Dionysus...”

Phaedra with an attendant, probably her nurse, a fresco from Pompeii. ( 60–20 BC )(Finn Bjørklid/ CC BY-SA 3.0)

Diminished to a lovelorn phantom, Ariadne laments her fate at the hands of two unworthy males. Even her younger sister Phaedra’s miserably unhappy marriage to Theseus, is not enough to assuage her grief. Reduced to a woman whose only source of happiness is through a man, the shadow of Ariadne in 400-500 AD –when Nonnus penned these lines—is poles apart from the independent great mother goddess she once was over 2,000 years prior.

Lady Of The Labyrinth

Honored in a religion of the soil that encouraged not only reverence for nature but respect for women, Ariadne became subjugated under a patriarchal society which relegated the female while exalting the male. With her identity brought down she was used as a foil for the men she would serve. Ariadne, however, was not the only great mother goddess thus subdued. Some believe that under the archetypal guises of the carnal Aphrodite, the jealous Hera and even the patriarchal Athena are vestiges of the great mother goddess tradition from whence they sprang. Much scholarship has been done on the thesis that beneath the greater Olympic pantheon - as envisioned by Hesiod and Homer - lay an underpinning of the older great goddess religions. If read closely this can be evident within Ariadne’s mythology when every so often, there is a glimpse into her primary manifestation as it was envisioned once in the primordial mist of prehistory.

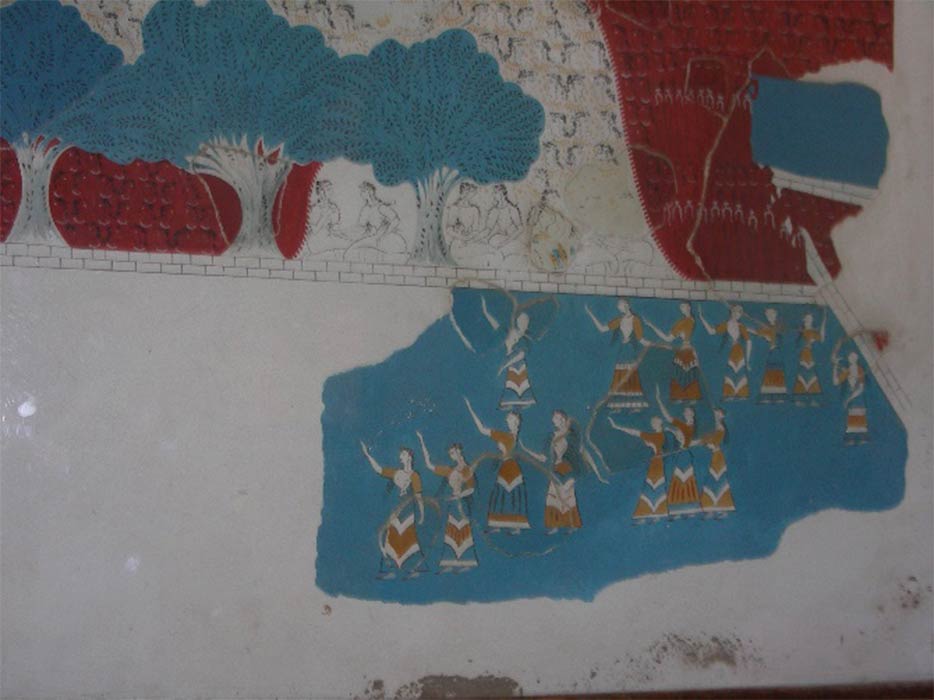

Fresco of Minoan women dancing at Knossos Palace. Crete (©Courtesy Micki Pistorius)

In spirals mimicking her labyrinth, the women whirled around dancing rhythmically. Their movements were designed to stimulate fecundity as they gesticulated and rotated in harmony with the planet’s own movement. In the center of the circle was Ariadne’s priestess—her physical incarnation on earth. Steeped in pageantry, she was every bit the goddess—outfitted in layers of gold and a kaleidoscopic costume only a deity could pull off. Designed to include adherents in an intimate setting with their deities, Minoan temples were as nonhierarchical as their society. Yet were the fertility festivals held in the temples or outdoors in the fresh air? Did the women chant as they danced around Ariadne’s persona? Were men involved in the ceremony? One can only guess. Even on a clear day, the view looking back over the span of epochs is hazy. One thing remains certain, in the paramount and indispensable domain of fertility—the women were in charge.

Mary Naples’ master’s thesis: “Demeter’s Daughter’s: How the Myth of the Captured Bride Helped Spur Feminine Consciousness in Ancient Greece,” examines how female participants found empowerment in a feminine fertility festival. Visit www.femminaclassica.com

Top Image: ‘Ariadne in Naxos’ (1877) by Evelyn De Morgan. (Public Domain)

By Mary Naples

References

Brindel, J. 1980. Ariadne: A Novel of Ancient Crete. St. Martin’s Press.

Burkert, W. 1985. Greek Religion. Harvard University Press.

Eisner, R. 1977. Some Anomalies in the Myth of Ariadne. The Classical World. Vol. 71, No. 3.

Herberger, C. 1972. The Thread of Ariadne. Philosophical Library.

Perry, L. 2013. Ariadne’s Thread. Moon Books.

Rigoglioso, M. 2010. Virgin Goddesses of Antiquity. Palgrave Macmillan.

Webster, T. 1966. The Myth of Ariadne from Homer to Catullus. Greece & Rome. Vol. 13, No. 1.