The Mysterious Identity Of The Eastern Pyrenean Lady With The Flaming Grail

Deep in the eastern Pyrenean valleys of Catalonia, Spain, lies a 900-year-old mystery. For some unknown reason, in the 12th century (between 1100-1170) at least nine medieval church apses were decorated with frescoes showing the Apostles and a woman, usually identified at Santa Maria, holding a vessel, which is often flaming. Including the Virgin Mary among the Apostles was unusual, and to have her holding a flame-filled vessel was even more so. In fact, the iconography is unique to this region.

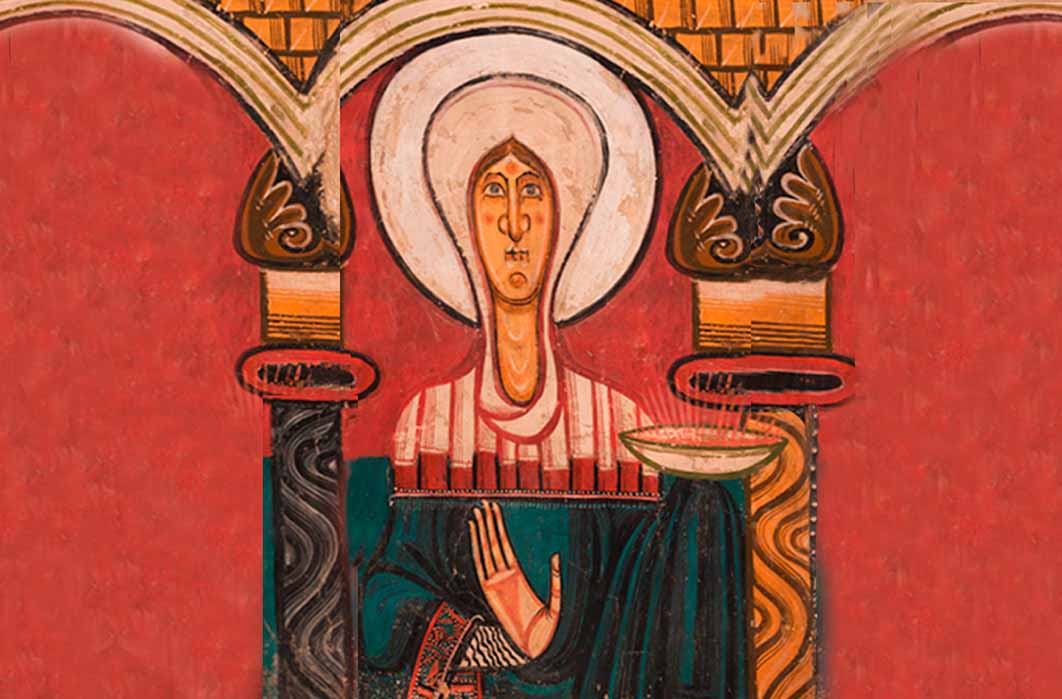

The woman from the fresco painted on the wall in the church’s apse, stares with a gaze clear and penetrating. Her right-hand faces palm out, as if to stay, “Stop! Pay attention!” Her left hand (hidden beneath the folds of her blue cloak) holds aloft a white bowl. Golden-orange rays rise from the flaming bowl. The bowl is or contains something holy, as demonstrated by the way she holds it in her covered hand rather than touching it directly. She is identified as Mary, but which Mary is she: the Virgin Mary or Mary Magdalene? And what is she holding? Is it possible she holds the Grail? And if so, why is it flaming? And what is its relationship to the Arthurian legends about the Holy Grail?

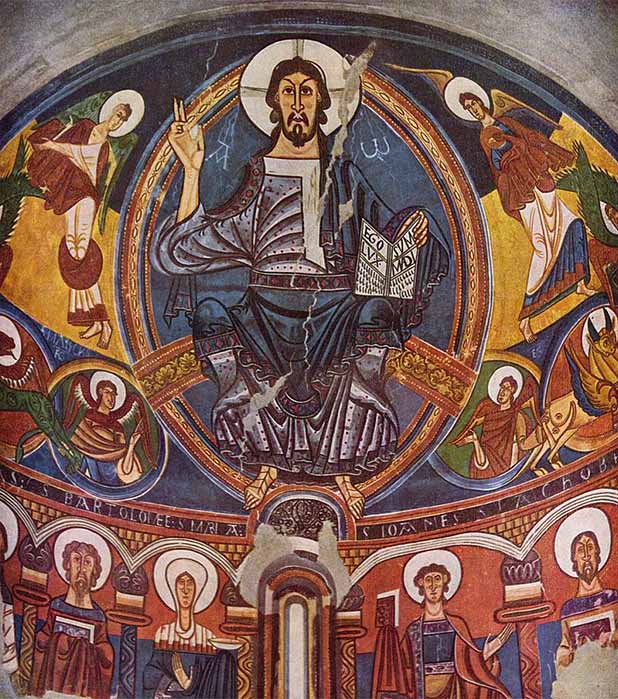

Christ the Pantocrator by the Master of Taüll, with the Lady holding the flaming Graill below his right foot (Public Domain)

Probably the earliest and most elegant depiction of this scene is in Sant Clement in Taüll, a Romanesque church consecrated in 1123. The exquisite wall frescoes were painted by an innovative and exceptionally skilled artist known only as the Master of St. Clement. The serving bowl or graal (often aflame) appears in different guises in eight other nearby churches, painted during a period of some 70 years. Sometimes the object resembles a lamp, sometimes a chalice, sometimes a cup, morphing in shape as if the artists were not quite sure what it actually was supposed to be. Or what it held. Or perhaps its exact shape was less important than one might think.

Perceval arrives at the castle, to be greeted by the Fisher King. (Public Domain)

Chrétien de Troyes’ Perceval and the Grail

The historian Joseph Goering points out how unusual these representations are. He suggests that these images, and the word graal, are the true origin of the Holy Grail, although they were painted at least 50 years before the first literary mention of the Grail, by Chrétien de Troyes in his work Perceval or the Conte du Graal, written in the late 12th century (somewhere between 1180-1190). Chrétien was based in northern France, near Paris, a distance from the Catalan Pyrenees. Chrétien’s story is set in Wales and describes events associated with the young Perceval, King Arthur’s Court, Gawain, the wounded Fisher King, and a strange procession in the Fisher King’s castle, in which unusual objects (a golden graal, a silver platter, candelabra, and a bleeding lance) are carried from one room to another by attractive young men and women. The hero, Perceval, fails to ask what it is he sees and thus fails to free the wounded Fisher King from his suffering. Devastated, Perceval sets off on a quest to find the graal and the procession once again.

The graal, the word Chrétien uses to describe this object, is an unusual term. It is not French. Its origin can be traced back to Occitan (the medieval language of French Languedoc, located on the border of the Pyrenees) or Catalan, where it was used to describe a domestic serving dish. It is not a cup, a goblet, a deep bowl, a platter, or a vessel. Chrétien calls the radiant serving vessel a graal and says it is made of glittering gold and adorned with jewels. But he is vague in his description of the shape of the object and he never offers a synonym (such as cup or platter) to describe it, either because it was not necessary (which was unlikely, since it was a foreign word) or because he was uncertain. He does not call the graal holy, and he seems to consider the bleeding lance in the procession as important as the graal.