Majestic Minoan Knossos: Palace Or Funeral Parlor

Before 1900, the general knowledge about an ancient civilization on Crete was limited to the Greek mythology of King Minos and the heroic Theseus, prince of Athens, who slayed the minotaur in the labyrinth and won the heart of the princess Ariadne, and of Daedalus, the architect of the labyrinth who designed wings for himself and his son Icarus to escape the island. That changed in 1900 when Sir Arthur Evans excavated what he called the ‘Palace of Knossos’, seat of the Bronze Age Minoan civilization. However, there are some anomalies in the theory of a palace. Was the magnificent construction perhaps inhabited by the deceased, and not the living Minoan elite?

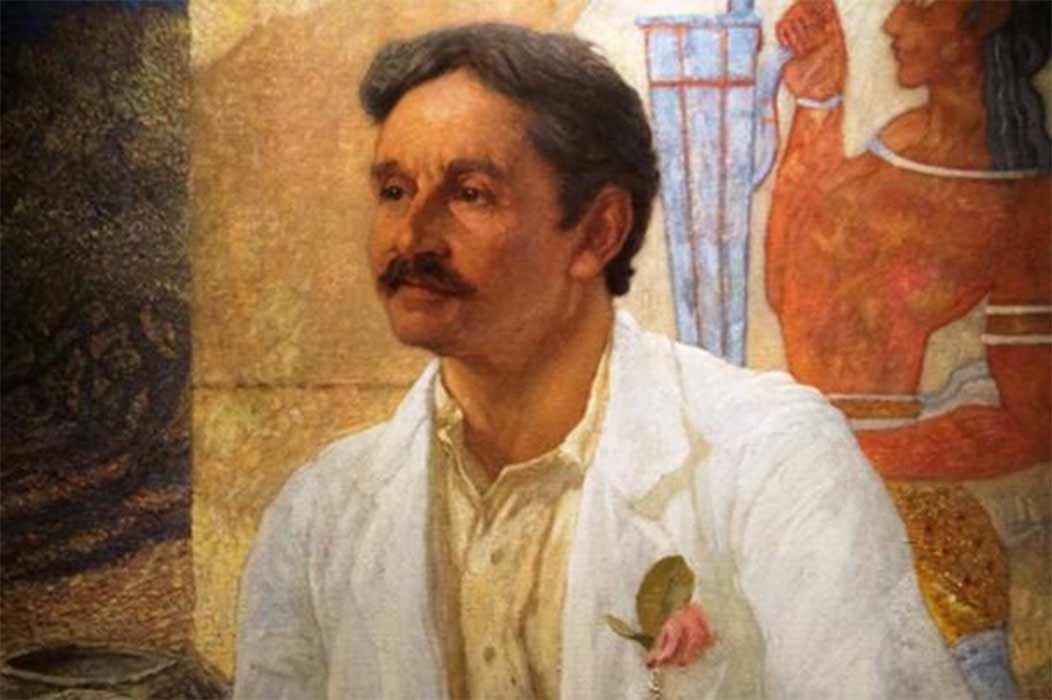

Portrait of Sir Arthur Evans by William Richmond, 1907 (Ashmolean Museum)

Sir Arthur Evans Enthusiastic Archaeologist

Arthur Evans was born in 1851 in Hertfordshire, as the son of an affluent archaeologist. He followed his father’s footsteps and was appointed as the curator of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and he was a professor in prehistoric archaeology at Oxford University. As curator of the Ashmolean Museum he developed a marked interest in the career and excavations of Heinrich Schlemann in 1876 at Mycenae, the historic stronghold and palace of Agamemnon, mythical High King who led the Achaeans to Troy in Homer’s Iliad. Evans had a particular interest in the seals that Schlemann had found. The seals were produced from stone and ivory and to Evans they hinted at an as-yet undiscovered lost civilization somewhere in the Mediterranean. Evans managed to buy similar seals in the markets in Athens and were informed of their Cretan origin.

Minoan seal of Bull leaping (c, 1700 BC) (Andree Stephan / CC BY-SA 3.0)

In 1894 Evans traveled to Crete for the first time, where he was taken to the hill of Kephala, just outside the capital of Heraklion. He was informed that an amateur Greek archaeologist, Minos Kalokairinos had discovered a storeroom with ancient pithoi in 1878 on this hill, but he was prohibited by the Tourkokratia or Turkocracy, the current regime at that time, to proceed with excavations. According to some authors it was the local population of Crete who prevented the excavations, as they feared that valuable artifacts would have been exported to Istanbul under the Turkish regime. By this time Schlemann had already made an offer to purchase Kephala, as well as the Italian archaeologist Federico Halbherr and the French archaeologist Andre Joubin. The Turks were finally expelled by Greece in 1898, and Evans was the right man at the right time. He managed to purchase a large portion of the Kephala Hill from a Moslem landowner, with his own funds, to the great consternation of other archaeological institutions.

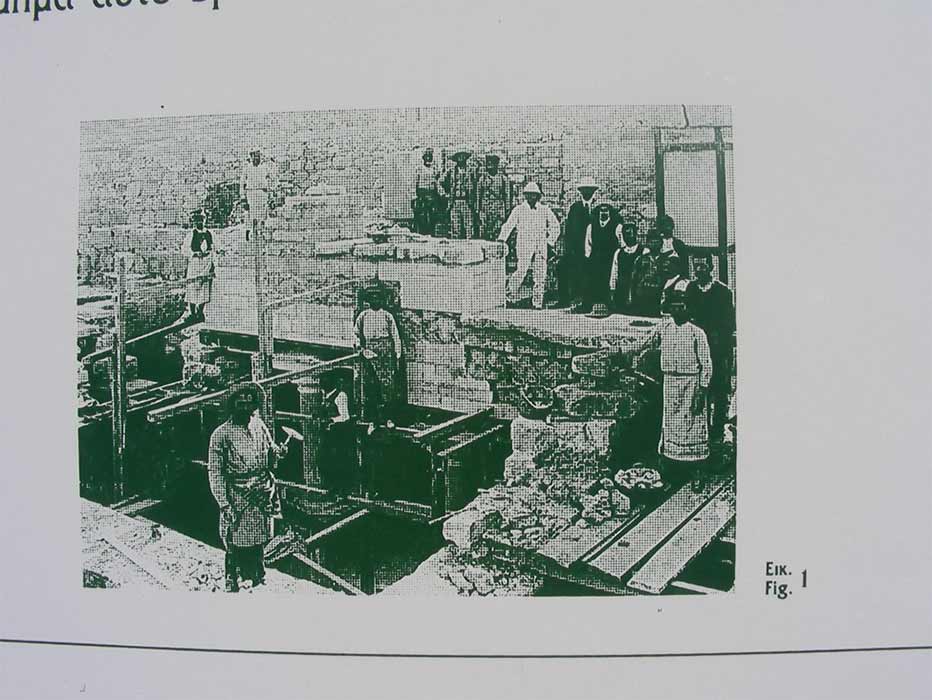

Sir Arthur Evans (in white) and his team excavating the stairwell. (Image: Courtesy: Micki Pistorius)

Evans’ Excavations At Knossos

On March 23, 1900 Evans and his team of 32 workers first broke ground at Kephala. Within a week this team grew to 100 workers and within a few weeks they had uncovered 2,500 square meters (26,909 square feet) of the eventual 13,000 square meters ( 139,930 square feet) of the ruins. Evans’ expert team consisted of Duncan McKenzie and the architect Theodore Fyfe, who was replaced by Christian Doll in 1905 and again later by the architect Piet de Jong; the Swiss artists and art restorers Emile and Edouard Guilleron (father and son); the Greek Grigorois Antoniou and the foreman Emmanuel Akoumianakis. Evans was one of the first archaeologists to appoint a fulltime architect and McKenzie was also responsible for recording the finds, which eventually culminated in a treasure of archived documents, sketches and photos.