Ramesses III and the Harem Conspiracy: Diabolic Plot to Kill the Living Horus Unfolds – Part I

The collapse of the Late Bronze Age world brought chaos to the shores of ancient Egypt. Vibrant trade and tributes from Near Eastern lands had all but ceased after the Sea Peoples decimated those kingdoms. Droughts that arose from climatic changes greatly hindered the production and distribution of food grains; and internal turmoil brewed owing to extraordinary economic hardship. In the midst of this period of enormous difficulties, in early April circa 1155 BC, a band of treacherous conspirators, including royals and palace staff, unleashed a diabolic plot which probably led to the death of the Living Horus. Little could the hapless victim, Ramesses III – often called the last great pharaoh – who had repeatedly and successfully crushed invasion attempts by multiple enemies of Egypt on land and at sea throughout his reign, have known that he was at his most vulnerable in his own royal palace.

Belzoni retrieved the great granite lid of Ramesses III’s sarcophagus from the king’s tomb in 1815, which he then presented to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, in 1823 (Henry Salt collected the sarcophagus box and sold it to the Louvre, Paris, in 1826).

Ramesses the Grand

Though meticulous record-keepers, the Egyptians steered clear from documenting negative events. Such instances included losses in battle, details of internal rebellion and most important of all – attacks on the king’s person. It is therefore a sheer quirk of fate that a set of papyri dating to the Twentieth Dynasty, which enumerate the dark saga of overarching ambition among a few that ended in the demise of a pharaoh, survived down the millennia.

The final years of the Nineteenth Dynasty were akin to a cauldron of confusion; one in which political machinations, deceit and devious designs held sway for the most part. At the dawn of the Twentieth Dynasty, the son of its founder-pharaoh Userkhaure Setepenre Setnakhte (and Queen Tiy-Merenese), Usermaatre Meryamun Ramesses-Heqaiunu, ascended the throne of Egypt. Better known as Ramesses III, he did not inherit an empire beset by a precarious or pernicious situation. But from Regnal Year 5 onwards, Ramesses’ reign witnessed umpteen campaigns against the Libyans and the dreaded coalition of forces known as the Sea Peoples. Through unquestionable grit and determination, this warrior-king defeated all his enemies and safe-guarded the sovereignty of the Egyptian state.

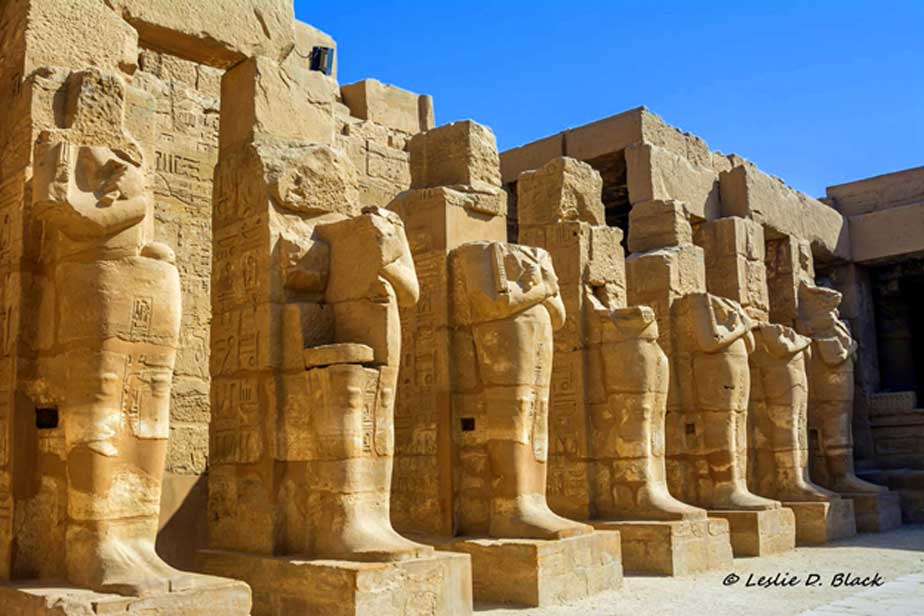

Colonnaded forecourt of the barque-shrine temple of Ramesses III, Heka-iunu, with Osiride statues of the king. The temple is remarkable for this period at Karnak, in that, it was built entirely of new material (predominantly sandstone).

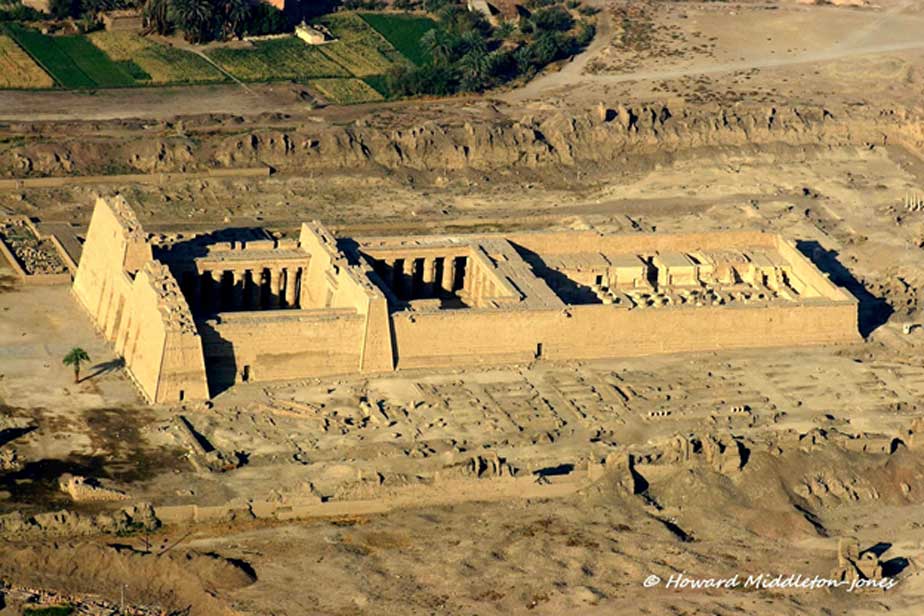

Blessed with extraordinary militaristic acumen, it is estimated that Ramesses III was 31 years old when he was crowned upon the death of his father. After achieving phenomenal victories against his arch rivals, he sent expeditions to faraway lands to amass great treasure in the form of copper and myrrh. Not since the time of Pharaoh Hatshepsut had vigorous trade of this sort been embarked upon. At this time, the king shifted the seat of power from the erstwhile capital city of Pi-Ramesses in the Nile Delta to Medinet Habu.

- Ramesses III, The Final Warrior Pharaoh: Savior of Egypt in Her Darkest Hour—Part I

- Enduring Mystery of the Screaming Mummy: Mortal Wounds and Divine Justice—Part I

- The Four Great Beauties, and the Arts of the Courtesans in Ancient China

From his magnificent palace-cum-mortuary temple called the ‘Mansion of Millions of Years’ that he had remodeled as a militaristic monument, Ramesses commissioned a nationwide inspection of temples. The entire royal court that had come to inhabit the precincts of this glorious edifice would have surely supported these initiatives of the ruler. But none of the endless grandiose proclamations and enterprises made sense to the deprived subjects; and soon, matters were set to plummet inexorably.