Striking at the Heart of Pharaoh: A Time of Pastries, Pain and Protests – Part II

The artisans and builders who resided at Set Ma’at (‘The Place of Truth’) were among the most valued workers in all of Egypt. Yet, there came a time when the economy of the country was on the verge of breaking down completely. Droughts, lack of tributes from Near Eastern vassal states that were decimated by the Sea Peoples; and corruption at home, resulted in driving the laborers to the very edge. The unprecedented outcome reveals a turbulent time in the lives of commoners who were forced to take matters into their own hands to ensure justice was served.

A view of the remains of massive pillars in the Hypostyle Hall in the Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu. While the pharaoh dined off gold and silverware, his subjects struggled to eke out a living; and could not even afford one square meal a day.

Trouble in Artistic Paradise

The residents of Deir-el-Medina encountered immense hardship during the reign of Ramesses III and matters came to a head in his 28 regnal year, when the payment of monthly wages of the highly skilled royal tomb-builders and artisans in the village of Set Ma’at (‘Place of Truth’, modern Deir-el-Medina) - payment which also included their food rations - were not provisioned. When there was no sign of any help forthcoming by the 20th day, the workers knew something was seriously amiss. This led to much dismay and anger amongst them.

The Turin Strike Papyrus, written by the scribe Amennakhte provides a blow-by-blow account of the workers’ struggle, and the corruption which had spread throughout the administration. Amennakhte wasted no time in rushing to the mortuary temple of Horemheb to negotiate with local officials for the distribution of 46 sacks of corn to the workers; but this was a stop-gap solution to a pressing issue. The administration did not get to the root cause: the enormous delay in payment. This matter would rear its ugly head sooner than one could have imagined.

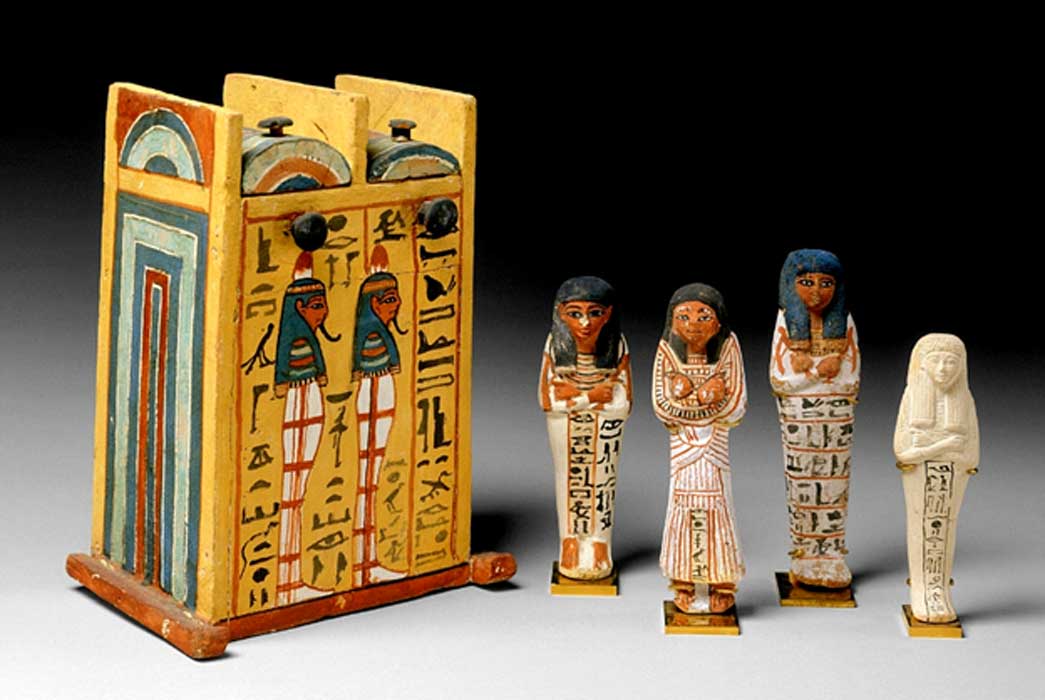

Shabtis come in many shapes, sizes and colors, as do their containers. This interesting shabti urn made of baked clay and its figurines are inscribed for the construction worker, Mesmeni. 20th Dynasty. Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. (Image: Petra Lether)

Over the next year, court officials and administrators throughout the land were immersed in making preparations for the impending Heb Sed (jubilee) of Ramesses III, so much so, that they completely ignored paying the necropolis workers. This resulted in the first known labor strike in recorded history by workers who: “… had grown used to enjoying better than average working conditions, and better than average remuneration”. Trouble began barely three months ahead of the much-awaited grand jubilee. Fed up after having waited 18 days post salary day in vain, the laborers downed their tools. It was a desperate move by them hoping to make the ruler pay attention to their woes.

Pastries, Pain and Protests

Year 29, second month of winter, day 10.