Hair-Raising Status of Ancient Gods and Men

Human hair has always played an important role in culture and in society. For men and women alike, styling one's hair seems to be an innate human desire to emphasize their beauty and power. Thus, apart from being interesting and rather beautiful, hairstyles in history have acted as markers that revealed a person's social status and membership of a tribe or group, social class, age, marital status, political beliefs, and many more.

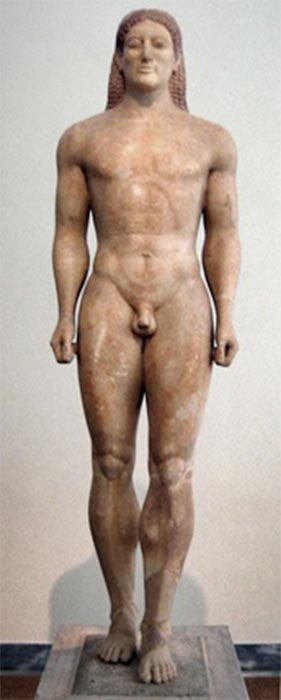

Kouros representing an idealized youth (circa 530 BC) (Public Domain)

Although, perhaps understandably, much attention has been given to ancient women's hairstyles, one should not underestimate the hairstyles of men in the ancient world. In ancient Greece, for example, beauty was all important to the men - perhaps even more so than to the women. A handsome, full-lipped, chiseled man in ancient Greece understood that his beauty was a gift of the gods and that a beautiful body was considered direct evidence of a beautiful mind. Therefore, a beautiful ancient Greek man had no qualms in spending more than eight hours a day at the gym to maximize his assets. Bearing this in mind, doubtless such a man would have considered it his duty to pay special attention to his hair as well. Somewhat similarly, the ancient Chinese believed that hair and skin were given to one by one’s parents. Therefore, cherishing one’s hair (keeping it long and luxurious) and skin (keeping it fresh and blemish-free) was the beginning of filial piety.

Painting of Zeus at Olympia (Public Domain)

Hairstyles of Ancient Greek Gods and Men

Many of the ancient Greek gods could be recognized by their distinct hairstyles, and throughout antiquity, these divine hairstyles acted as models for human hairstyles. Zeus typically aligns his hair upward, followed by a sweeping flow of hair which then radiates outward, creating a crown of individual strands. Asclepius, the god of healing, is the only god who wears his hair like Zeus.

Bust of Dionysos. Ephesus Archaeological Museum (CC BY-SA 3.0)

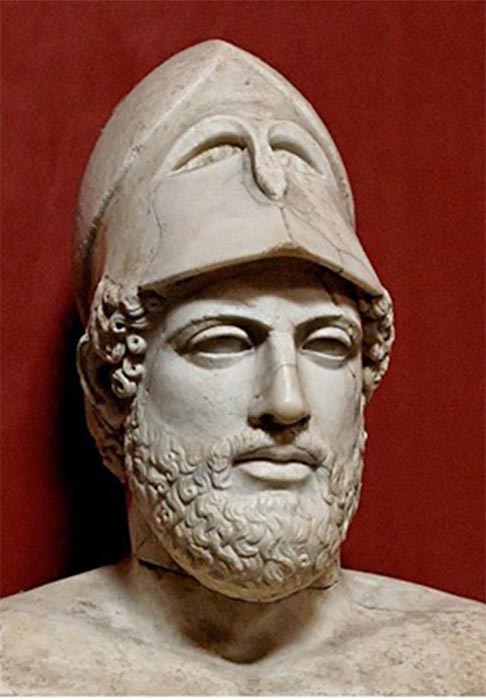

Compared to these noble gods, Dionysos and his adherents, who conducted orgiastic rituals, developed an anti-thesis equivalent of the divine hairstyle. Dionysos himself is sometimes portrayed with hermaphrodite features, with wide shoulders, a slightly stooped posture, and long hair peeled back from his face into a knot, hiding his ears. Satyrs are portrayed with on-end-standing front hair, pointed ears, and small horns on their heads. The Silens (elderly satyrs) wore an ivy wreath to cover their bald spots, as baldness was seen as a sign of ugliness in Homer's time. The bald-headed Socrates likened his own appearance to a Silen. Some baldness was also experienced by Homer and by Euripides, the Athenian tragic playwright, with his remaining oily hair hanging to the sides. In contrast, Plato displayed a full head of hair, but he wore it unstyled. Pericles, the successful Athenian statesman, knew how to present himself. He dressed himself in the fashion of the helmeted Athena, with carefully trimmed beard and hair.

Pericles, wearing a helmet like Athena. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Pottery and frescoes from the Minoan period depict dancers and athletes with shoulder-length black hair in the great palaces, especially in Knossos. Likewise, Aegean art shows men with single or double plated hair. Homer's heroes also had such hair, like the warriors at the battle of Marathon in 490 BC. Up to about 500 BC, the male youth wore their hair shoulder-length, or even more finely braided, which was a highly artificial and time-consuming habit of the privileged nobles. Men began trimming their hair by the middle of the fifth century, traditionally due to their achievements in sport. The shorter hairstyle of the athletes became very popular.

Frescoes at Knossos (Crete) and Akrotiri (Thera) of Minoan men with long hair. (Images: Courtesy Micki Pistorius)

Portraits of Alexander the Great with ascending locks forming a central parting, became the model for the Hellenistic kings. Since there was no beard among all younger Greeks, Alexander proceeded to trim his beard, thus promoting youth as an ideal in his day. He was, in fact, the first king of Greece not to wear a beard. Soon, at least for the next several years, it became unfashionable for the emperor to sport a beard.

Roman Emperors’ Baldness and Vanity

In ancient Rome, although men's hair may have needed no less daily attention than women's, the community presented a radically different social reaction to it. While women's hair was painstakingly styled according to different techniques, extended grooming sessions would have been considered a taboo for men.

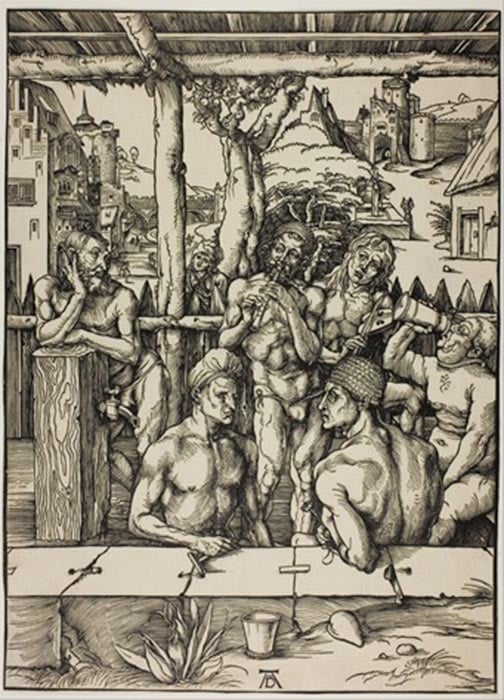

The Men's Bath by Albrecht Dürer (circa 1496-1497) (Public Domain)

It is likely that in earlier times Roman men wore their hair long, as it was not until about 300 BC, with the introduction of barbers called tonsors, that it became customary to wear short hair. Hairdressing duties and maintenance in affluent ancient Roman households fell upon the trained hairdressers of the household who were usually women. However, for those men who did not have access to private hairdressing and shaving services or for those who preferred a more social atmosphere, they could go to the tonstrina (barbershop) for a bit of a gossip with other patrons. Barbershops of the time were places for social gatherings as well as the first shave of a young man which was often celebrated in the neighborhood as a passageway to manhood.

- Big Wigs and Hairpieces: Artificial Hair of the Ancient World

- Did Blondes Have More Fun in the Ancient World?

- Medusa and the Gorgons: The Origins of the Legendary Tale

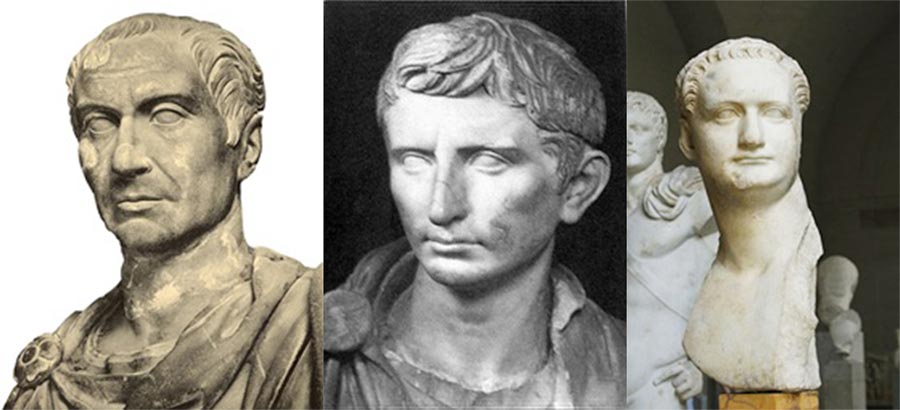

Roman emperors were most often known as the trendsetters of hairstyles. One constant characteristic of portraits of Augustus, for instance, is his hairstyle with its distinctive forked hair locks on his forehead. Nero began the trend of an intricate curly hairstyle and sideburns. After the Flavian Age, most men had short hair trimmed on the crown. A straight hair cut with frontal bangs was common among men during Trajan’s rule for the next few decades. Hadrian started the trend of wearing a beard, and after him many of the emperors continued the trend. Although this has usually been seen as a mark of his devotion to Greece and the Greek culture, the Historia Augusta claims that Hadrian wore a beard to hide blemishes on his face.

Caesar (Public Domain); Augustus (Museo Capitolino of Rome/Public Domain); Domitian (José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Particularly in the Republican era, from 509 to 27 BC, male baldness signified wisdom and gravity. Male baldness was therefore considered an ideal characteristic of an upstanding Roman citizen and was used in portraits of philosophers to convey venerability. At the time, Roman portrait patrons preferred to be portrayed with gleamingly bald heads, broad noses and extra wrinkles to reflect the years they had dedicated to the Roman state. However, despite the air of patriotism associated with baldness, a receding hairline outside of the realm of portraiture was not as desirable. Ovid, in his Ars Amatoria, wrote: “Ugly are hornless bulls, a field without grass is an eyesore. So is a tree without leaves, so is a head without hair.” The famously bald Emperor Domitian was said to have lost much sleep over his hair loss. Suetonius quoted him as saying: “Be assured that nothing is more pleasing, but nothing shorter-lived” as having hair. By the time Julius Caesar was in power, being bald was seen as a deformity. Therefore, Julius Caesar went to great pains to hide his thinning hair by combing his thin locks over his head's crown. Seemingly understanding the gravity of the situation, the Senate allowed Caesar to wear a laurel crown to hide his disappearing hairline.

As both balding and going grey were associated with Roman men’s deteriorating health and vitality, hair dyeing proved to be a popular practice. However, there was no escaping satire and any man trying to disguise a receding hairline was in for a constant mockery of poets such as Martial (Marcus Valerius Martialis) who wrote in his Epigrams: “Your hairs are carefully disposed, Lest your bald head should be disclosed.” (Epigrams, 10.83)

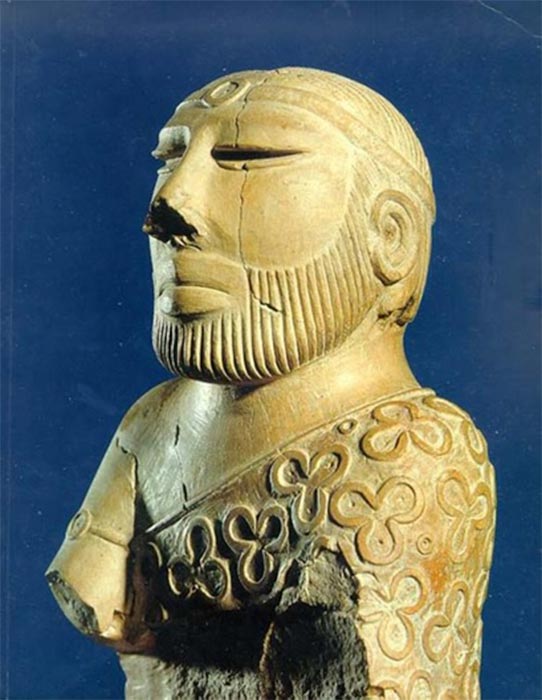

So-called "Priest King" statue, showing a neat hairstyle and trimmed beard. Mohenjo-daro, late Mature Harappan period, National Museum, Karachi, Pakistan. (CC BY-SA 1.0)

Indus Valley Combs

In ancient India, hair is historically associated with charm and power. Although Shiva and Parvati wear their hair in matted locks or jata, early art portrays the hair of Buddha as curly. During the Harappan civilization, hairstyling was highly in vogue, as can be seen from the artifacts found at various Harappan sites, including Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, Kalibangan, Dholavira, Rakhigarhi and Banawali. Combs were used by the Harappans, a number of which were unearthed at Kalibangan and Mohenjo-daro. Oval-shaped tanged copper mirrors from Kalibangan and Rakhigarhi were also excavated.

Many terracotta pieces show men with their hair combed back. It was either cut short or coiled in a knot at the back with a fillet for support. Sometimes, a part was knotted and another part hung freely. In some cases, one part was knotted and another curled. Another form was for the men to gather their hair up in a bun or coil it in a ring form on top of their head. In the terracotta male figurine from Patna, the men’s hair is brushed back in streaks with a fillet on the head, a horn-like arrangement on the head and a knot on the right.

Two gentlemen engrossed in conversation while two others look on, dated to the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 AD) Museum of Fine Arts Boston. (Public Domain)

Ancient China’s Hair-Raising Status Symbols

In ancient China, hair and hairstyling was important to men and women alike. The hair was highly cherished as, apart from the filial duty requiring its maintenance, it symbolized much more than beauty or personal expression. A person’s hair was a declaration of many aspects of one’s social status, political affiliations and life choices. Therefore, the ancient Chinese treasured their hair as a sign of self-respect. A punishment called kun in the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC) forced sinners to shave their hair and beards. This was considered more damaging compared with other physical punishments as it hurt the sinner’s spirit and, literally, cut his bond with his parents. During the Warring States Period (475-221 BC), the legendary General Cao Cao was spared the death sentence. Instead, his hair was shaved off as a punishment for disobeying military orders.

A portrait of General Cao Cao from Sancai Tuhui (1607) (Public Domain)

A man’s hairstyle also helped to differentiate between the Han people, at the time a newly formed dominant ethnicity, and other ethnic groups, as the Hans bound their hair while others usually favored disheveled long hair. The adult Han men twisted their long hair up into a bun on top of their heads and sometimes covered the bun with linen. The Han Dynasty had also based its coming-of-age ceremonies around a hairstyle shift. When a young Han man reached the age of 20, a ceremony was held where he was given a special cap and a different name for adulthood. After this ceremony, he would officially become an adult and he would style his hair into a bun.

In the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD) different shaped hairdos developed into a symbol of class status. Later, when the Manchu people took over the sovereignty in 1644, one of the first things they did was to force male citizens to shave their heads into the traditional Queueue hairstyle. Two years later the Qing rulers infamously ordered that all the male Han Chinese people should adopt the long classic plait as a symbol of submission to their new rulers. Such was the resistance that the crime of not cutting one’s hair was declared treason, punishable by death.

Martini Fisher is a Mythographer and author of many books, including "Time Maps: Matriarchy and the Goddess Culture” | Check out MartiniFisher.com

Top Image: Samson and Delilah by Domenico Fiazella (1650) Louvre (Public Domain)

References

Chang, S. 2015. Hair raising history. Thewordlofchinese. Available at: https://www.theworldofchinese.com/2015/07/hair-raising-history/

Fisher, M. 2019. Is Life Easier for Beautiful People. Available at : https://martinifisher.com/2019/12/13/is-life-easier-for-beautiful-people-great-men-evil-women-and-standards-of-beauty/

Haas, N, et. al. 2005. Hairstyles in the Arts of Greek and Roman Antiquity. Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings, Volume 10, Issue 3.

Han, B. 2013. A History of Hair. China Daily. Available at: http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/epaper/2013-02/15/content_16224636.htm

Warner, M. 2015. No pain no rogaine, hair loss and hairstyle in ancient Rome. Available at:

https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/no-pain-no-rogaine-hair-loss-and-hairstyle-in-ancient-rome

Hujiang Chinese. 2013. A history of Chinese hairstyles. Available at: https://cn.hujiang.com/new/p533598/

Pathak, N. 2016. Hairstyles from ancient and medieval India. Available at: https://gulfnews.com/entertainment/arts-culture/hairstyles-from-ancient-and-medieval-india-1.1653120