Egyptian Elysium: Connecting the Realms of the Living and the Dead in the Greco-Roman Period

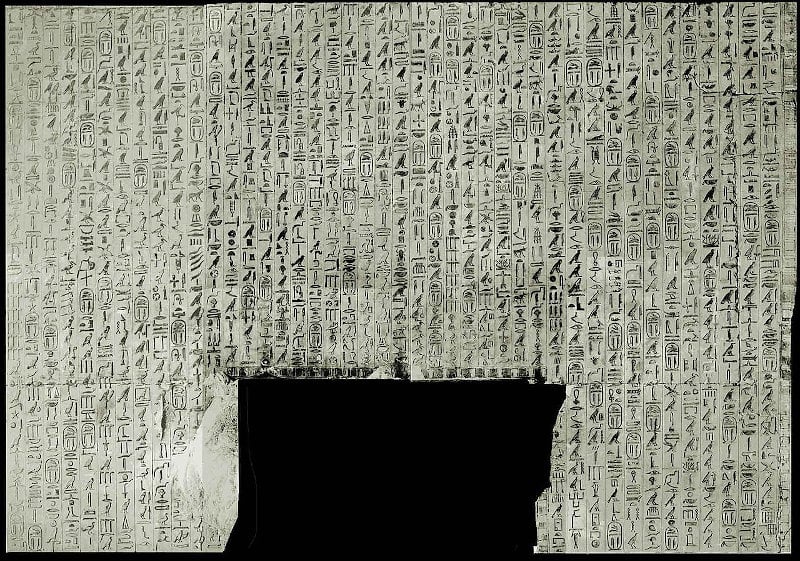

The long history of Egyptian afterlife writings began during the 3rd millennium BC, when the body of compositions known as the Pyramid Texts were carved onto the walls and coffins of the pyramids of Old Kingdom rulers at Saqqara, the necropolis of the ancient capital of Memphis. The function of the writings was to ensure that the ‘spiritual’ components of the deceased—the Ba and the Ka—were reunited after separating upon the death of the material body. The unification of these spiritual elements caused the deceased to be reborn as an Akh, which may be described as a transcendent, celestial being. As summarily explained by James Allen (2005:7):

“At death, the ka separated from the body. In order for an individual to survive as a spirit in the afterlife, the ba had to be reunited with its ka, its life force: in the Pyramid Texts and elsewhere, the deceased are called ‘those who have gone to their kas.’ The resultant spiritual entity was known as an akh: literally, an ‘effective’ being. No longer subject to the entropy of a physical body or the limitations of physical existence, the akh was capable of living eternally, not merely on earth but also in the larger cosmic plane inhabited by the gods.”

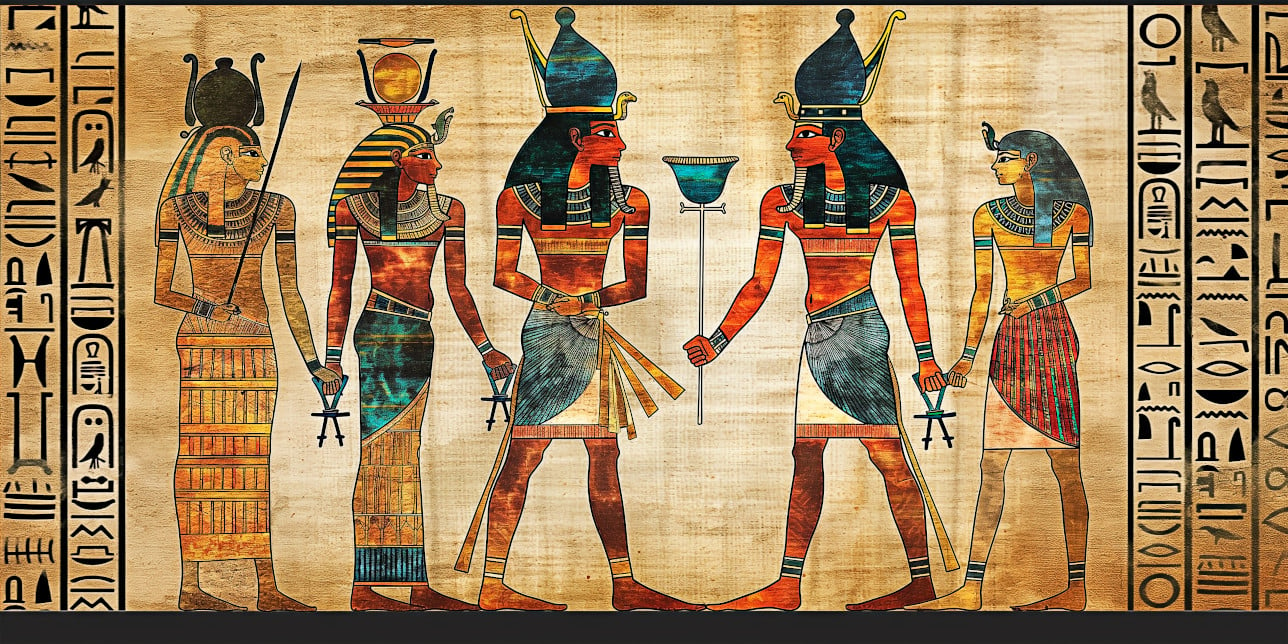

The Pyramid Texts established the two themes that would permeate Egyptian afterlife literature for thousands of years: transfiguration and reintegration. Through a ritualized process of embalming, mummification, and entombment the deceased would be reborn into an immortalized condition with access to the various planes of being. From the earliest times the journey of the Ba-soul of the deceased to attain this blessed condition was correlated with that of the Sun god Re as he traveled through the underworld at night following sunset and to then unite with Osiris so as to emerge reborn at dawn. The deceased was therefore closely associated with the forms assumed by Re during his journey across the sky during the day and through the nethersky in the underworld at night.

- Egyptian Temples and the Order of Creation: Embodying Eternity in Time

- IWNW The Egyptian Atlantis, City of Yah Weh and Ra

The Greco-Roman Renaissance

The above-mentioned themes informed Egyptian afterlife texts throughout the ages, including the Coffin Texts, The Book of Amduat, The Book of Gates, The Book of Caverns, The Books of the Sky, and The Book of the Dead. While these texts are well-known in both academic and non-professional circles, what has received considerably less attention is the fact that the last centuries of the Egyptian civilization when the country was under Greek and then Roman rule witnessed a virtual renaissance in the field of afterlife literature.

Pyramid text utterance 302-312 (Unas pyramid). (Public Domain)

Although the large corpus of new afterlife texts composed during the Greco-Roman period were configured around ideas present in the more ancient writings, they also considerably amplified certain themes. One such theme was the access of the transfigured dead not only to the realm of the stars and the underworld, but also to the terrestrial world of the living to actively participate in the religious feasts and festivals held in the various sacred centers of Egypt throughout the year. During the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 BC) this concept of “going forth by day” was associated with the wish that the deceased be able to participate in the mysteries of Osiris at Abydos, and during the ensuing New Kingdom (1550-1069 BC) the number of festivals expanded until, as explained by the prominent German Egyptologist Jan Assmann (2005:230), “there took shape a canon of major festivals in which the deceased wished to participate after their death.” The Greco-Roman period text entitled The Book of Traversing Eternity has been considered to represent the final historical development of this concept.

Traversing Eternity

The Book of Traversing Eternity is an excellent example of the type of literature that ultimately succeeded more ancient compositions such as The Book of the Dead during the last centuries of the Egyptian culture. Although the title of this work (mḏꜢ.t n.t sbỉ nḥḥ) is translated as the Book of Traversing Eternity (hereafter simply Traversing Eternity), the actual terminology conveys one of the central purposes of the text: to grant the deceased the power to ‘traverse’ (sb) the totality of temporal-material time and space (nhh). This is suitable to a text which not only allowed the transfigured dead access to the earth, the underworld, and the celestial sky, but also participation in a multitude of Egyptian religious feasts and festivals held at specific times throughout the year.

Although Traversing Eternity is known from more than 20 extant samples from Thebes, Esna, Abydos, Hawara, and Sebennytos, the longest known recension of the text (P. Leiden T 32) was composed in hieratic sometime in the 1st century AD for Harsiesis, a priest from Thebes who held the titles “god's father and god's servant of Amun-Re king of the gods, god's servant of Khonsu the one who exercises authority in Thebes, god's servant of Bastet who dwells in Thebes, overseer of the mystery, purifier of the god, wise in rituals, who knows his utterance.” In the opening invocation Harsiesis is assured that the physical and spiritual components of his being will persist in the various realms of existence:

“Your ba will live in the sky in the presence of Re. Your ka will be divine among the gods. Your corpse will endure in the underworld in the presence of Osiris. Your mummy will be glorious among the living.”

Become a member to read more OR login here